Originally presented as the keynote address at the Sixth Biennial Meeting of the Defoe Society, July 2019.

DEFOE’S PROTAGONISTS—that is, the protagonists of those novels we attribute to Defoe—tend to be curious in several ways. To conventional members of society, they represent the danger of transgression: they are rebels, outcasts, or criminals, violators of mores, morals, property, family, fate, and God: thieves, pirates and adventurers like Moll Flanders, the pickpocket, Roxana, the whore, and even H.F., the merchant narrator of The Journal of the Plague Year, who riskily ventures from mere curiosity into the stricken parts of the city. At the same time, they exhibit curiosity: the wanderlust and restless urge to investigate that marks their rejection of their place in the sphere into which they were born; their drive to rewrite their designated roles or characters. Indeed, novels featuring protagonists with extreme desires or in dramatic situations resulting from their inquisitive natures were popular at the time: Eliza Haywood’s Love in Excess, for example, with its concupiscent heroine ravening on lust, was published the same year as Defoe’s book and was immensely successful with readers intrigued by the forbidden. All of these characters are thus both curious about the world beyond their experience and are themselves curiosities: people whose transgressions propel them beyond the norm into the realm of the outlandish, transforming them for the reader—and, in Robinson’s case, for himself—into subjects of inquiry.

Crusoe’s dilemma segregates him from his historical, geographical, and social identity, casting him as nearly non-human, an ontological transgression: a human exiled from humanity (Benedict, Curiosity, 1-23).[1] Although the eighteenth century was the age of conversation, his is the “sad Tale of a silent life.” He longs for his dog to talk; he tames a “sociable” parrot just to hear a voice cawing his nominal identity; searching for any sort of companionable presence, he domesticates a cat and a goat to comfort him. In a period that celebrated sociability as virtue, he has no human companion at all for many, many years before the arrival of Friday (Defoe 47, 87, 104). Moreover, as man’s control over the material world and nature was reaching fresh heights, Robinson can contrive only the most basic tools, clothes and shelter from primitive materials, and fails to manufacture the commodity designed for communication, ink. And at a time when art, especially printed literature, was becoming the center of culture, he has only the Bible to read and is forced to scratch out his Journal with his wasting ink supply. In this period of intensifying commodification, commercialism, and a love of things, Robinson lands on the Island of Despair stripped and dependent on collecting things from the ship and land.[2] Bereft of companions, communication, and comforts, reduced to a bare, forked thing, his greatest resource is his curiosity: his investigation and accumulation of the world about him.

Because of their transgressiveness—whether it be cause or consequence—Defoe’s characters are also essentially, often terribly, alone. Indeed, their aloneness makes them especially curious. Robinson Crusoe is Defoe’s most extreme example of an exile, isolated from mankind, and thus also his most extreme example of a curiosity. His very identity is isolation: as Irene Basey Beesemyer says, “to be the Crusoe, he must be the shipwrecked, island-bound isolato, the man of perpetual solitude,” and many other critics have discussed his loneliness and its relationship to his spiritual development (Beesemeyer 81). However, equally significant is the connection between his isolation and his curiosity: his inquiries, and his status as an anomaly. In this novel, solitude and curiosity, loneliness and inquiry, exist in a powerful relationship: the pain of being alone spurs the search for a cause and hence a solution, and investigation into the natural world in turn peoples it with phenomena made newly and emotionally important. The term “curiosity” has etymological and cultural roots associated with collecting; the “habit of curiosity,” in the Renaissance, was the activity of accumulating works of cura or careful workmanship. This second meaning also informs the curiousness of many of Defoe’s characters, notably Moll Flanders and Roxana, both obsessed with piling up money and precious objects. Robinson’s curiosity also possesses this feature: his solution to aloneness is a particular form of collection that reinvents his isolation as acquisition. This essay examines the way Robinson’s curiosity about his world and his status as a curiosity inform one another and define his identity.

Curious Isolation

Robinson’s solitude occupies several registers of significance. His aloneness enacts the aloneness of man without God; it also rehearses the aloneness of the explorer in strange lands, and it dramatizes the aloneness of human consciousness in a world of dumb material. It makes the material world seem hostile and seems to set his soul—his desires, his feelings—apart from or subject to his body. Several literary genres had already addressed this issue of the relationship of man to an often hostile, often unknowable nature. Foremost amongst them is the georgic. Virgil’s rediscovered Georgics were enjoying great popularity in the early eighteenth century, and like Defoe’s novel, they constitute more than merely instructions on raising crops. They also serve as treatises on the ambiguous power of nature, “which nurtures and tortures while it tracks the cycle of seasons,” as Adam Budd observes, thus purifying the spirit as well as feeding the body (Budd 3). The retirement poem, another revived classical genre popular at the time, also sings the delights of a private life in the countryside: the imagined idyll of a self-contained existence where the person needs and wants nothing.

Both of these genres inform Robinson Crusoe. The book constitutes a kind of prose georgic: a literary how-to manual deigned to improve spiritual strength through focused productive labor on the land, but it also functions as a marvelous tale (Kareem 74-104). If Robinson Crusoe mingles religious adjuration with careful accounts of experiments, like building boats and huts, raising goats, and growing corn, and Robinson periodically praises his self-sufficiency, he also exemplifies the anomaly of a fundamentally social animal without society. Indeed, the tension between Robinson as Everyman and Robinson as the Only Man runs throughout the novel.

Loneliness is the marker of Robinson’s extraordinariness. In the eighteenth century, it was associated with melancholia, a humoral and increasingly medicalized, psychological disorder. Robinson describes his narrative as “a melancholy Relation of a Scene of silent Life” (Defoe 47), and melancholia assails him throughout his ordeal. Thinking of how he might have been surprised and destroyed by the cannibals, he records, “after seriously thinking of these Things, I should be very Melancholy; and sometimes it would last a great while,” even though such a fate can no longer happen. He calls his Island a “Prison” (71), and himself a “Captive,” (100) and he reports that before he learns to recognize God’s grace,

as I walk’d about, either on my Hunting, or for viewing the Country; the Anguish of my Soul at my Condition, would break out upon me on a sudden, and my very Heart would [sink, thinking on how I] was a Prisoner, lock’d up with the Eternal Bars and Bolts of the Ocean, in an uninhabited Wilderness, without Redemption: In the midst of the greatest Composures of my Mind, this would break out upon me like a Storm, and make me wring my Hands, and weep like a Child: Sometimes it would take me in the middle of my Work, and I would immediately sit down and sigh, and look upon the Ground for an Hour or two together; and this was still worse for me; for if I could burst out into Tears, or vent my self by Words, it would go off, and the Grief having exhausted it self would abate. (100).

This description evokes Albrecht Durer’s portrait of Melancholy, seated on the ground, holding her head and staring down. Indeed, Robinson’s imagined fears, his metaphors and responses here reflect the contemporary understanding of melancholia: the experience of utter desolation, one of the kinds of madness that accorded eighteenth-century tourists of such asylums as Bedlam spectacular delight (Foucault).[3]

Melancholia has a robust history in early English medicine and is frequently characterized by aloneness. Burton’s 1631 Anatomy of Melancholy, a comprehensive and popular compendium of seventeenth-century thought on the matter, calls it a “spirituall Disease,” and finds that “Folly, melancholy and madness and but one disease, delirium is a common name to all” (Burton Part. 1. Sect. 2. Memb. 1. p. 173; Sect. 5. Memb. 4. p. 341; Sect.1, p. 29).[4] He finds many causes, among them the “Losse of Liberty” and “Imprisonment” that Robinson endures, and the primary, original cause: the “fear and sorrow” that derive from the sin of disobedience to God, and lead to another key cause of melancholy: despair, despair, which is the ultimate sin against God because it denies his grace. This is one of the most important threats to Robinson on the Island, the Island he in fact calls “the Island of Despair” (Defoe 52). Burton finds, “The impulsive cause of…miseries in man [is] this privation or destruction of Gods image, [which] the sinne of our first parent Adam in eating the forbidden fruit” (Burton Part. 1, Sect. 1, Memb. 1, Subs., 122). Robinson too finds the root cause of his suffering in his disobedience to his Father.

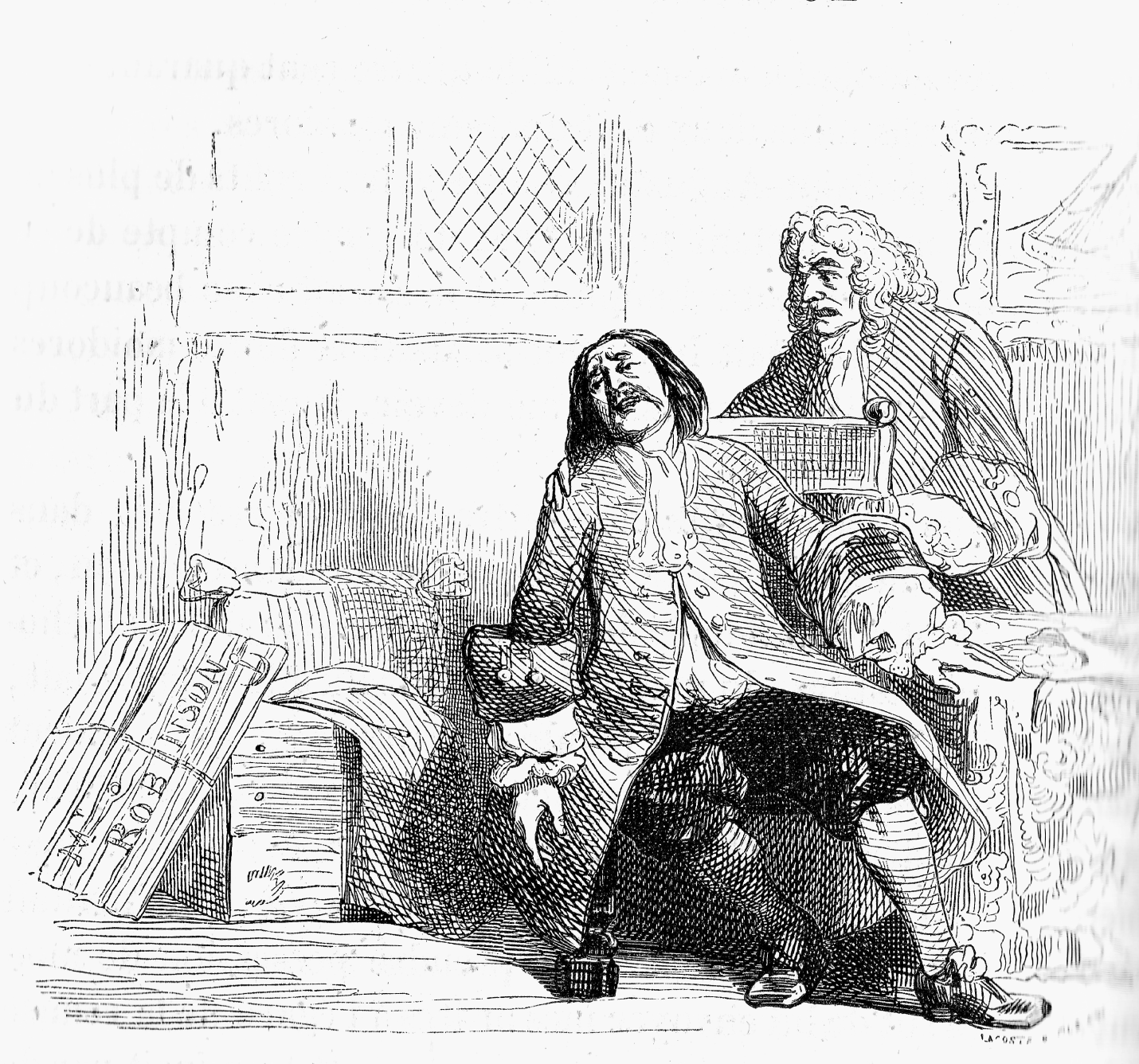

This realization enables Robinson to collect his experiences and characterize his exile as an object of contemplation itself. John Locke uses “to collect” to mean “to understand,” and the verb “to recollect” signifies both to collect again or anew—that is, to gather together freshly—and to re-understand (Jager 324, 323). Robinson exercises this re-collection when he learns to prioritize his own internal experiences over the documentation of the Island’s riches: he records that, when he begins to run out of ink, he “contented my self to use it more sparingly, and to write down only the most remarkable Events of my Life, without continuing a daily Memorandum of other Things” (Defoe 76). This process turns the chaos of daily experience into narrative. He confesses, “I have been in all my Circumstances a Memento to those who are touched with the general Plague of Mankind…that of not being satisfy’d with the Station wherein God and Nature had plac’d them;” when he relates his experiences to the abandoned Spaniards, he represents them as a “Collection of Wonders,” a marvelous tale, and “a Chain of Wonders” (140-1, 186, 197). His written account likewise serves to shape experiences that seem meaninglessly repetitive, or endless and fruitless, into a comprehensible whole.

Eighteenth-century philosophers and physicians commonly identified three other causes of melancholy: solitude, idleness and obsession, all of which they considered intensified by imagination. Robert Burton reiterates this point in The Anatomy of Melancholy, and so too does the physician John Armstrong in his poetic treatise The Art of Preserving Health (1744). Armstrong observes,

‘Tis the great art of life to manage well

The restless mind. For ever on pursuit

Of knowledge bent, it starves the grosser powers:

Quite unemploy’d, against its own repose

It turns its fatal edge, and sharper pangs

Than what the body knows embitter life.

Chiefly where Solitude, sad nurse of Care,

To sickly musing gives the pensive mind.

There Madness enters; and the dim-eye’d Fiend,

Sour Melancholy, night and day provokes

Her own eternal wound. The sun grows pale;

A mournful visionary light o’erspreads

The cheerful face of nature: earth becomes

A dreary desart, and heaven frowns above.

Then various shapes of curs’d illusion rise:

Whate’er the wretched fears, creating Fear

Forms out of nothing; and with monsters teems

Unknown in hell… (IV, 84-101)

Robinson is notoriously restless: indeed, learning resignation to God’s will is his mental project on the Island. His imprisonment there forces him to “confine” his “Desires,” and to manage his “restless mind” (Defoe 141). He is also tormented by fear: of cannibals, or animals, or the unknown. As he discovers, “Fear of Danger is ten thousand Times more terrifying than Danger it self, when apparent to the Eyes” (116), and from experience, he learns to pull his imagination into his reason, to pull himself together: to collect himself.

This self-collection is propelled by Robinson’s search for a reason for his exile, a logic to his suffering: an external cause for what, at first, he finds pointless punishment. This re-envisioning entails seeing his experiences as a collection, rather than an assemblage of events. When he discovers that the cannibals had been visiting the Island all the while he was there, unaware, he reports:

It is as impossible, as needless, to set down the innumerable Crowd of Thoughts that whirl’d through that great throrow-fare of the Brain, the Memory, in this Night’s time: I ran over the whole History of My Life in Miniature, or by Abridgement, as I may call it, to my coming to this Island. (142)

This reflection leads him both to thankfulness that he remained ignorant of the cannibals and to a renewed desire to leave: the contradictory gratitude to God and the resurgent restlessness and discontent that marks his character. Robinson figures his process of distilling the road-trip of his memories as both a literary genre, the newly popular abridgement, and a painterly one, the miniature, again shows him organizing his experiences not only as a narrative but as a coherence: something grasped quickly and as a whole, just as a collection constitutes both an assemblage of separate items and a unity. Moreover, Robinson’s account not only constitutes an increasingly selective collection of incidents, but also a history of the circumstances that make Robinson a curiosity himself. In recording his accumulated marvelous episodes as a “collection,” Robinson documents this collecting: his understanding and his accumulation of the Island’s riches in the fashion of a spiritual autobiography. As George Starr shows, this procedure resembles that of spiritual autobiographies designed to systematize personal reflection and improvement through regular self-examination and recording (Starr).

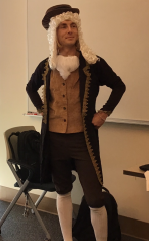

However, if Providence provides the plot, Robinson constitutes the subject. People—foreign and racially-different people—constitute another typical curiosity that Robinson encounters both before and after his long exile on the Island. As several critics have noted, they constitute a form of collectible, some physically acquired by Robinson, and some captured in his narrative and memory. Robinson is a slave-trader, and accordingly, he trades his “Boy Xury,” despite the lad’s loyalty, and accumulates the indigenous Friday (Defoe 27). Although these people fit the conventional European category of a curiosity because of their perceived racial difference from Europeans and their foreign customs, neither this foreign-ness nor Robinson’s normativity remains stable; in fact, Robinson himself becomes de- or re-racinated as a native—a feature of the novel’s appeal exploited by editors in frontispieces illustrating Robinson in his outlandish gear. This corresponds to the manner in which Robinson describes himself emphasizes his curiousness: both his scientific perspective and his status as a man half-European, half-native—as a categorical transgression. He is a vehicle of collected artifacts:

I had on a broad Belt of Goat’s-Skin, dry’d, which I drew together with two Thongs of the same, instead of Buckles, and in a kind of a Frog on either Side of this. Instead of a Sword and a Dagger, hung a little Saw and a Hatchet, one on the other. I had another Belt not so broad, and fasten’d in the same Manner, which hung over my Shoulder; and at the End of it, under my left Arm, hung two Pouches, both made of Goat’s-Skin too; in one of which hung my Powder, in the other my Shot….As for my Face, the Colour of it was really not so Moletta like as one might expect from a Man not at all careful of it, and living within nine or ten Degrees of the Equinox…I had trimm’d [my beard] into a large Pair of Mahometan Whiskers, such as I had seen worn by some Turks, who I saw at Sallee; for the Moors did not wear such…of these Muschatoes or Whiskers, I will not say they were long enough to hang my Hat upon them, but they were of a Length and Shape monstrous enough, and such as in England would have passed as frightful. (109)

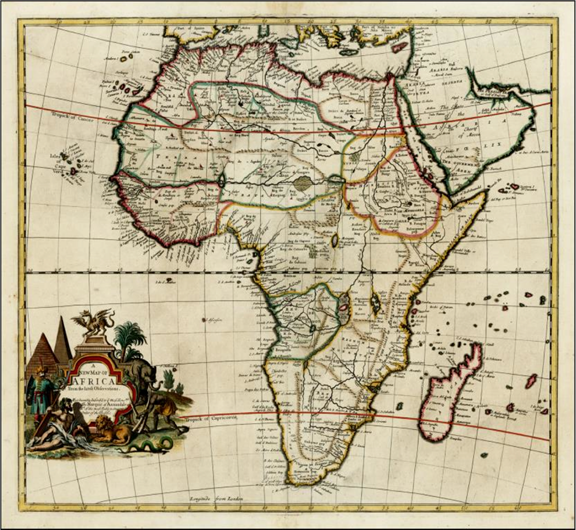

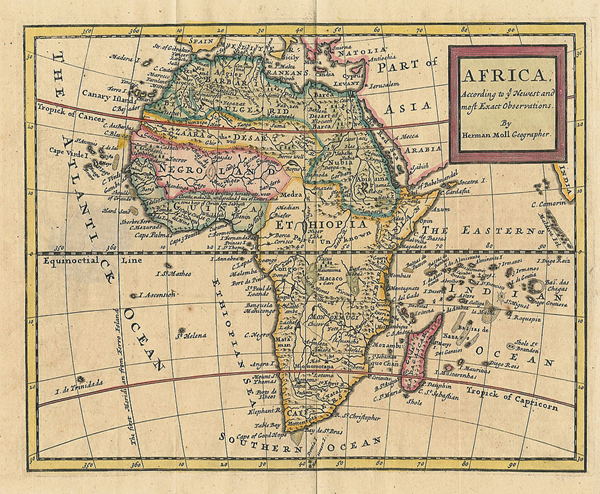

Rather than describing his apparel in the active voice, as the result of his choices—“I hung my Saw and Hatchet,” for example—most of this description presents Robinson as a costumed indigenous oddity. Robinson paints a meticulous empirical portrait of the way he would look to an observer. This defamiliarizing technique echoes those used by, for example, Aphra Behn’s narrator in Oroonoko in describing the native of Surinam, and similar early-modern ethnographical accounts by travelers to the Indies and Africa. Exiled from humanity and adrift from Europe, Robinson is both the subject and the object of his own curiosity.

Collecting the Island: Natural Curiosities

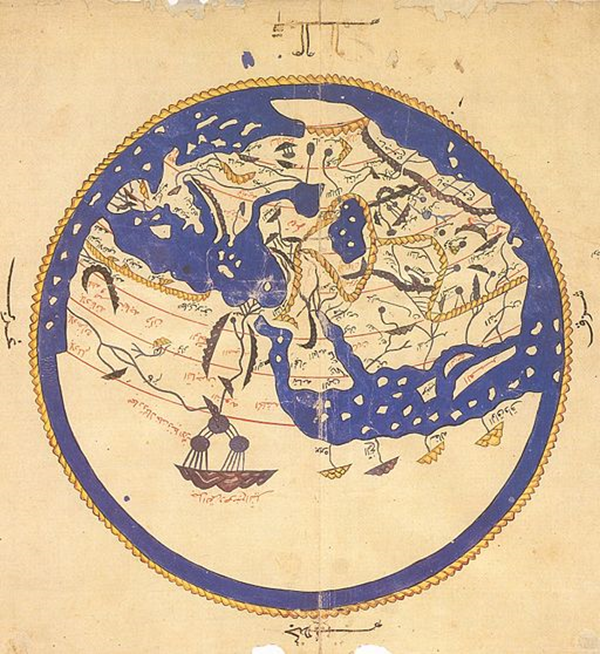

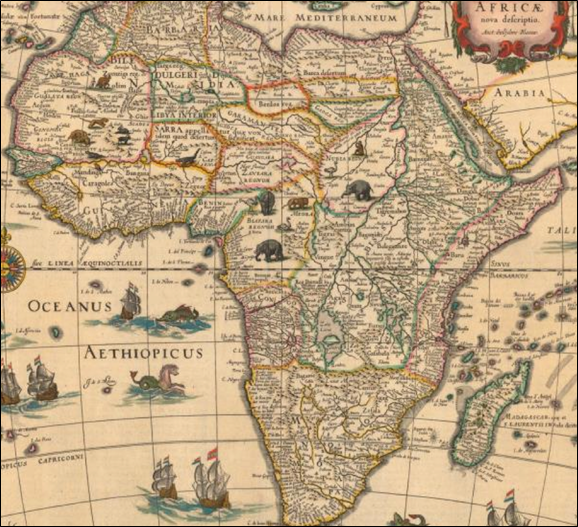

Self-collecting entails exercising power over rambunctious or rebellious feelings, and this is Robinson’s project on the Island. Self-collecting resembles collecting itself as an exercise over the material world and a proclamation of identity. Since the Renaissance, collecting, the “habit of curiosity,” had been a means of control and display: in cabinets of curiosities ranging from rooms to cupboards, European royalty and aristocracy and clergy exhibited their collections of precious objects and natural rarities to select audiences to dramatize their power, and churches contained repositories of precious relics, secreted in dedicated, semi-private rooms, to induce wonder and humility in their congregations (Impey and MacGregror, Hudson, MacGregor).[5] By the later seventeenth century and into the eighteenth, repositories of naturalia had become similar theatres for scientific study and collecting a national passion: the Royal Society for the Advancement of Learning contained an extensive repository, as did other scientific societies (Delbourgo, Benedict, “Collecting Trouble”). Seen through the lens of the collector, the world appeared stuffed with collectibles, and all objects during this period, be they natural, cultural, or artistic, came to hold a particular charge as emblems of civilization, material memories of past ages, vessels of cultural alienation, markers of human survival, exhibits of artistic transcendence.[6] Collecting them, especially in quantity, correspondingly became a means of control over a world expanding geographically and culturally and a way of positioning oneself in that world (Appadurai, Stewart).

Objects on the Island function this way for Robinson in his role as a collector. Before the arrival of Friday, Robinson follows the practices of contemporary scientific explorers and natural philosophers both in his investigation of the Island and in his accumulation of it: the domestication of the land itself and the conversion of its materials into goods (Watt, McKeon, Hunter). He explores the Island methodically, collecting information about its natural features as recommended by the Royal Society, and records them, as Jason Pearl has shown, in the fashion of its members, like Lawrence Rooke, Robert Boyle, and Henry Oldenburg, “using a plain style of commentary devoid of self-aggrandizement and romantic embellishment” (Hayden 18). The fellow Royal Society member, John Woodward, specified directions for the recording of information in his 1696 pamphlet entitled Brief Instructions For making Observations in all Parts of the World: as also For Collecting, Preserving, and Sending over Natural Things, Being an Attempt to settle an Universal Correspondence for the Advancement of Knowledge [sic] both Natural and Civil.[7] This treatise recommends keeping strict records of the winds, tides, water salination, and so forth, and in factual language, carefully differentiates subcategories and variations. These become lists or inventories of natural phenomena. His types of “Weather,” for example, includes, “Heat and Cold, Fogs, Mists, Snow, Hail, Rain, Spouts or Trombs, vast Discharges of Water from the Clouds,” and numerous other particularities of climate [Max Novak observes that Defoe knew the methods of the Royal Society and studied the causes of winds] (Novak 220).

Robinson follows Woodward’s formula. His accounts of his voyages aboard ships and the tidal pulses and movements of the sea, of the lay of the Island, its coves and groves, caves and shores, exhibit a similar process: observation and documentation based on experience as the experience is unfolding. Robinson’s observational specifications on the sea and winds indeed follow Woodward’s recommendations: they inventory and map the land and document its riches: Woodward specifies, “Springs, Grottoes, and Mountains, Trees, Earthquakes. Plants and Animals” (Defoe 2-3). Robinson also documents the natural phenomena he encounters, including a bird, which “I took to be a Kind of Hawk, its Colour and Beak resembling it, but had no Talons or Claws more than common, its Flesh was Carrion and fit for nothing” (40). (It is typical of Robinson immediately to evaluate his scientific information in terms of its practical use: he is a pragmatic not a speculative scientist. He does not document nature for its own sake at this point in the narrative, although later he learns to value the Island’s beauty.) (Tobin 1-31).

One example of Robinson’s scientific observation occurs after Robinson has left the Island. It is when Robinson, his Guide, and Friday travelling through the Spanish mountains encounter the Bear. Robinson reports,

As the Bear is a heavy, clumsey Creature, and does not gallop as the Wolf does, who is swift and light; so he has two particular Qualities, which generally are the Rule of his Actions; first, As to Men, who are not his proper Prey; because tho’ I cannot say what excessive Hunger might do, which was now their Case, the Ground being all cover’d with Snow; but as to Men, he does not usually attempt them, unless they first attack him: On the contrary, if you meet him in the Woods, if you don’t meddle with him, he won’t meddle with you; but then you must take Care to be very Civil to him, and give him the Road; for he is a very nice Gentleman, he won’t go a Step out of his Way for a Prince; nay, if you are really afraid, your best way is to look another Way, and keep going on; for sometimes if you stop, and stand still, and look steadily at him, he takes it for an Affront; but if you throw or toss any Thing at him, he takes it for an Affront, and sets all his other Business aside to pursue his Revenge; for he will have Satisfaction in Point of Honour; that is his first Quality. The next is, That if he be once affronted, he will never leave you, Night or Day, till he has his Revenge; but follows at a good round rate, till he overtakes you. (211)

This remarkably accurate description familiarizes the unfamiliar by humor and social satire, combining pragmatic advice with the natural observation of the animal’s behavior and responses. The ensuing account of Friday teasing the creature for Robinson’s amusement dramatizes the control over nature enabled by subduing it for personal pleasure that characterizes collecting.

Another way in which Robinson follows the practices of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century scientists is by collecting and organizing the materials he finds in language and writing. This is his way of making sense of a chaotic experience. When he deconstructs the ship, his finds “a great many Things…which would be useful to me” (Defoe 40). Amongst them are:

two or three Bags of Nails and Spikes, a great Skrew-Jack [for lifting heavy objects], a Dozen or two of Hatchets, and above all, that most useful Thing call’d a Grindstone…two or three Iron Crows…two Barrels of Musquet Bullets, seven Musquets, and another fowling Piece…(41)

In addition, he accumulates powder, small shot, sheet lead, mens’ clothes, a hammock, bedding, canvas, ropes, rigging, the sails, planks, bolts, casks, chests, bread, rum, sugar, flour, cables, razors, scissors, knives, forks, and, of course, thirty-six pounds in gold and silver coins (40-43). He also retrieves “three very good Bibles,” the plurality of which indicates their status as collectibles rather than reading material (48). This cornucopia of objects marshalled into a litany is mesmerizing: these constitute relics from the distant world that once was his own. Moreover, Robinson organizes the things he has retrieved from the ship in a traditional style. He groups his finds into loose categories reflecting their function but does not arrange them in a hierarchy, instead using a rough chronology that records when and where he found them. This method mimics that used by such collectors as John Tradescant, Elias Ashmole, Sir Hans Sloane, and Ralph Thoresby in their catalogues of their curiosity-cabinets and early museums (Wall).

Like these collectors, too, Robinson includes collectibles: objects made into curiosities by virtue of being detached from their meaning and place, and thus purposeless even while they remain provocative and stimulate inquiry and wonder. These are the silver and gold coins. Coins were a prominent part of most early museums and a subject of great interest amongst collectors, especially ancient coins (Addison wrote a treatise on them, and Pope a poem), but they were valued for their memorial not their monetary function (Benedict, “Collecting Trouble”). Robinson has both European and South American coins, and although originally intended for currency, they too now work as oddities: exotic, possibly intrinsically valuable, but functionally useless on the Island, now that they have been removed from their social and cultural context and exchange value. They do, nonetheless, still stimulate philosophical speculation. In the famous passage, Robinson exclaims, “Oh Drug!…What art thou good for?”, and moralizes on the coins’ worthlessness, like Pope in his poem “To Mr. Addison, Occasioned by his Dialogues on Medals,” written in 1713 and revised in 1719, the year of Robinson Crusoe’s publication (43). Robinson sees in the coins only, as Pope puts it, “the wild Waste of all-devouring years!” (Pope 215). These gold and silver curiosities metaphorically point to how Robinson himself is a curiosity on the Island: a man severed from his context, his culture, his usefulness, and history itself. Indeed, in the same way, the white Spaniards on the mainland are themselves curiosities to the indigenous people.

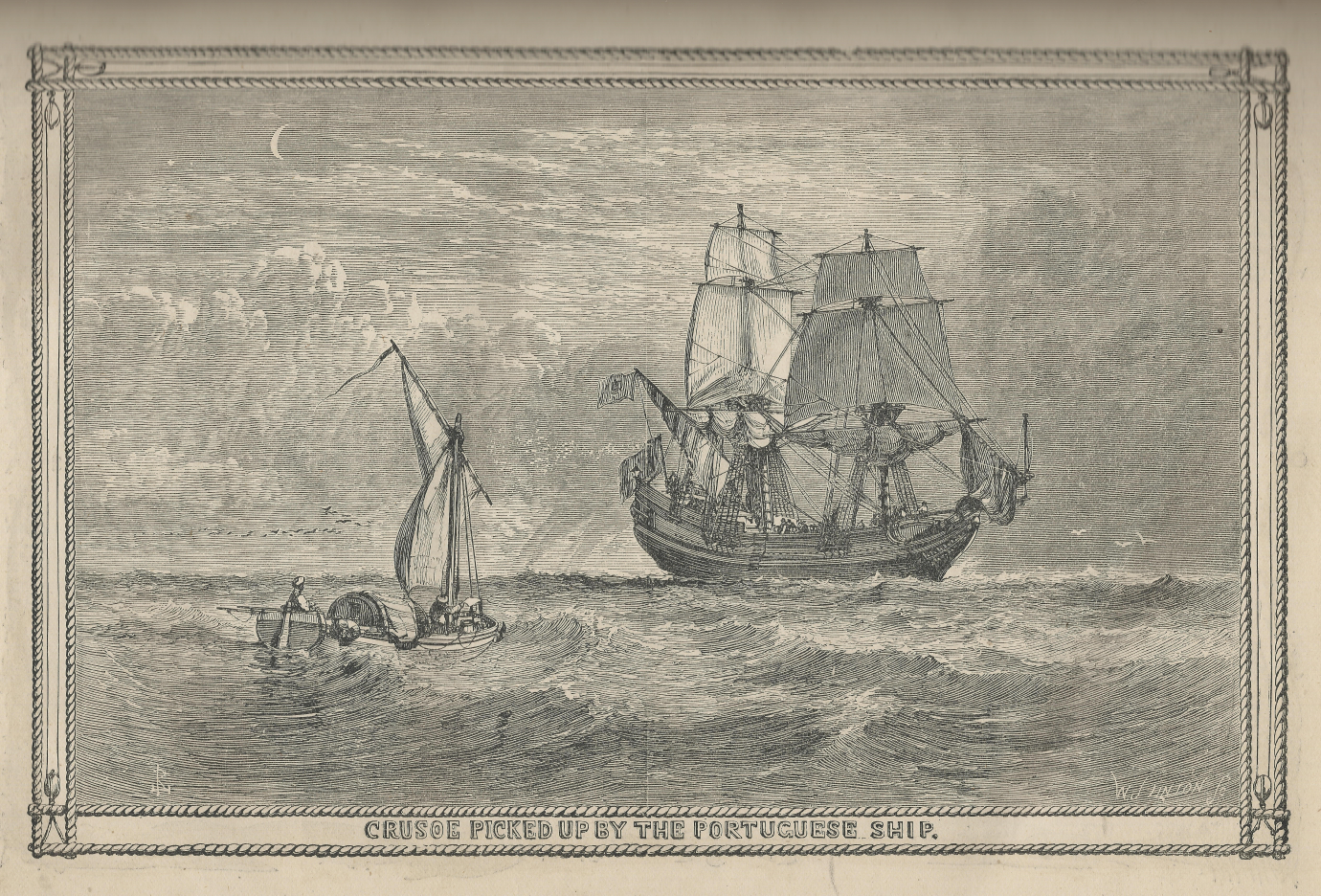

The Island of Despair, which seems at first a desert, actually bursts with objects to collect and subjects of inquiry: natural and artful curiosities: goats, cats, caves, hills, gold and strange birds, and eventually, cannibals, Spaniards, and, of course, Friday. Robinson also makes his own “curious”—that is artfully-made and also exotic—objects: canoes, clothing, baskets, pots (Walmsley). Indeed, by the time he leaves the Island, he possesses his own, selective collection of things that constitute material memories. When the charitable Portuguese Captain rescues him from his early adventure and transports him to Brazil, he refuses to rob Robinson of his goods. Robinson “immediately offered all I had to the Captain of the Ship, as a Return for my Deliverance,” but the Captain replies, “’if I should take from you what you have, you will be starved there, and then I only take away that Life I have given”’ (Defoe 26). Accordingly, ”he ordered the Seamen that none should offer to touch any thing I had; then he took every thing into his own Possession, and gave me back an exact Inventory of them, that I might have the even so much as my three Earthen Jars” (26).

Robinson’s solitude drives his curiosity and invests curious phenomena with meaning. Curious objects function as markers of the ambiguous borders between superstition, science, and religion. The dying goat that Robinson encounters in the cave exemplifies the way his empirical imperialism domesticates the threatening unknown into a reflection of himself, so that he becomes the Island and the Island becomes him. The description opens with an empirical explanation of the cause for the shining stars within the cave:

I perceiv’d that… there was a kind of hollow Place; I was curious to look into it, and…I found it was pretty large; that is to say, sufficient for me to stand upright in it, and perhaps another with me; but I must confess to you, I made more hast out of than I did in, when looking farther into the Place, and which was perfectly dark, I saw two broad shining Eyes of some Creature, whether Devil or Man I knew not, which twinkl’d like two Stars, the dim light from the Cave’s Mouth shining directly in and making the Reflection. (128)

The star-light of the goat’s eyes turns the cave upside down: looking inward becomes looking upward to the heavens. By echoing Plato’s description of the cave in which the unenlightened rely on empirical perception for truth, the passage suggests an allegorical meaning reinforced by the religious theme in this novel, as in Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. It hints that Robinson’s redemption lies in erasing the borders of Self and Other. While both God and Friday represent this Other in important ways, so too does the source of his unhappiness: the Island’s ominous solitude. By making himself the ominous Other, Robinson begins not merely to own the Island, but to incorporate it as part of himself.

Significantly, in the subsequent passage, Robinson extends his understanding of his own curiousness by recognizing it to himself. When he speaks to his “self” as to an Other, he realizes that he has permitted part of himself to operate beneath reason, to become an alien force of fear:

after some Pause, I recover’d my self, and began to call my self a thousand Fools, and tell my self, that he that was afraid to see the Devil, was not fit to live twenty Years in an Island all alone; and that I durst believe there was nothing in this Cave that was more frightful than my self. (Defoe 128)

Here, Robinson recovers his “self” that had been dazed by terror, and identifies the source of his fear as the very recognition of this self. This recognition is compelled by solitude: living “all alone” on the Island appears equivalent to seeing the Devil.

While Robinson’s self-recognition forms part of his religious redemption, it also serves to clear the way for his ownership of the Island. By associating the Island itself with his solitude, he recognizes that his loneliness is the source of the “frightfulness” of the Island. The goat both empirically and allegorically represents the misperception of seeing the Island as the enemy, and both empiricism and piety enable Robinson to revise this perception. As Robinson approaches, he hears the goat ominously “Sigh, like that of a Man in some Pain…follow’d by a broken Noise, as if of Words hale express’d, and then a deep Sigh again” (Defoe 129). These sounds cement the mirroring of the goat and Robinson, both alone suffering in the dark. However, once Robinson “encourages my self…with considering the Power and Presence of God…to protect me,” he rushes forward and perceives, illuminated by a flaming firebrand, “a most monstrous frightful old He-goat,” a phenomenon of natural not supernatural monstrosity.

This escape from superstition to empiricism enables Robinson to explore the Island as his if it were his own territory. This, his ensuing exploration of the cave reveals a treasure trove. Once he returns the following day and penetrates deep within the cave, crawling through a narrow passage, he perceives a treasure trove: a heaven within the Island (as within the Island of himself).

When I got through the Strait, I found the Roof rose higher up, I believe near twenty Foot; but never was such a glorious Sight seen in the Island, I dare say, as it was, to look around the Sides and Roof of this Vault, or Cave; the Walls reflected 100 thousand Lights to me from my two Candles; what it was in the Roc, whether Diamonds of any other precious Stones or Gold, which I rather suppos’d it to be, I know not. (129)

The cave becomes his “Grotto,” his cabinet of natural curiosities, a place of rarity and wonder equivalent in the natural sphere to the artful repositories of princes. Robinson’s curiosity invests the Island of Despair with significance: both natural and supernatural, emblematic and literal, it prompts Robinson to realize that he is, himself, the most terrifying phenomenon on the Island, and that his solitude is his safety. Having lost the fear of aloneness, Robinson reaps the rewards of the Island, no longer a prison but a storehouse.

Conclusion

Collecting serves Defoe as a secular practice to make the material world part of the spiritual one. In Robinson Crusoe, Robinson practices it to give his life meaning, to escape melancholia and fear and to transform episodic experience into narrative. When Robinson leaves the Island, he carries with him a memorial collection (although he must abandon the giant canoe):

for Reliques, the great Goat’s-Skin Cap I had made, my Umbrella, and my Parrot; also I forgot not to take the Money I formerly mention’d, which had lain by me so long useless, that it was grown rusty, or tarnish’d, and could hardly pass for Silver, till it had been a little rubb’d, and handled; as also the Money I found in the Wreck of the Spanish Ship. (200)

This little curiosity collection fuses money and memento, memory and material: his collections and recollections. However, as well as the contents of the Ship, Robinson collects the products of his own labor: goat-skins, baskets he has made, corn and other foodstuffs. He surrounds himself with hand-made curiosities: artifacts of his own manufacture people his lonely world. Scientific practices of observation, collecting and cataloguing enable Robinson to make sense of the Island’s resources and survive physically on it. His physical, imaginative, and spiritual survival intertwine. Solitude, as much as survival, turns Robinson into a curiosity. It enables him to define his life, his adventures, and himself as marvelous. As Virginia Birdsall explains, “Just as he tames outward nature by cultivating more and more land, so he tames inner energies by…[the] conquest of inner space” (Birdsall, 37-38; qtd. in Beesemyer 84). He familiarizes the strange physical world to transform it into home. His collections extend from the Ship’s contents to the island’s plentiful natural goods.

Collecting is an imaginative exercise designed to personalize the material world, to make things into meanings, to control and counter the solitude and isolation of the human condition. The apparent division between these two realities, between the internal and external worlds, appears as the duality of loneliness and hard physical labor in Robinson Crusoe, a duality many critics have found reflected in his life (Swados 36; Pearl 140; Backscheider). Sir Walter Scott identified this process in Defoe’s story as Robinson grows from “a brawling dissolute seaman” into “a grave, sober, reflective man,” and Beesemyer explains that, for Defoe, “true solitude—comprehension and appreciation of one’s solitariness that give rise to a singular perception of personal integrity—can only arise out of and follow an externally imposed isolation experience; this alone permits the individual both to access and to hold conversation with the community of the inner self” (Scott 77; qtd. in Beesemyer 83). But the essential corollary to this self-recognition is the imaginative possession and absorption of the surrounding material world, not simply as a mercantilist but as an imaginist.[8] The “large earthenware Pot” that Virginia Woolf famously found herself staring into, instead of into Robinson’s soul, in fact, represents not the banality of the narrative but the essential connection between Robinson’s physical and psychic survival (Woolf 45). Correspondingly, the mental project of forging a self from memory makes past and present coherent. Robinson’s curiousness and his curiosity become one.

Trinity College

NOTES

1. I define “curiosity” as an “ontological transgression empirically registered”: that is, as a violation of categories of being that is perceived through the senses.

2. Particularly recently, studies of the literary uses of objects has burgeoned following the seminal 1985 study of commodification of eighteenth-century British culture, The Birth of a Consumer Society.

3. See also Plate #8, “Scene in Bedlam,” of William Hogarth’s “Rake’s Progress” (1735), which depicts a melancholic figure as one of the types of the mad in an asylum.

4. See also Reid.

5. See especially MacGregor 1-30.

6. For studies of objects and material culture in eighteenth-century literary studies, see Berg and Clifford, Blackwell, Lamb, McCracken, Brown, Pearce, Festa, especially 67-132, and Benedict, “Saying Things.”

7. For the critical appraisal of Crusoe as a representation of the economic or commercial man, see Backscheider, Ambition and Innovation, 235; Koch, 35-36; and Svilpis.

8. Initially, Woolf complains that “there is no solitude and no soul. There is, on the contrary, staring us full in the face nothing, but a large earthenware pot.” However, she concludes that, “Defoe, by reiterating that nothing but a plain earthenware pot stands in the foreground, persuades us to see remote islands and the solidity of the human soul” (Woolf 48). See also Kraft, 38.

WORKS CITED

Appadurai, Arjun. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge UP, 1986.

Backscheider, Paula. Daniel Defoe: Ambition and Innovation. Kentucky UP, 1986.

——. Daniel Defoe: His Life. Johns Hopkins UP, 1989.

Beesemyer, Irene Basey. “Crusoe the Isolato: Daniel Defoe Wrestles with Solitude,” 1650-1850: Ideas, Aesthetics, and Inquiries in the Early-Modern Era, vol. 10, March 2004, pp. 79-102.

Benedict, Barbara M. “Collecting Trouble: Sir Hans Sloane’s Literary Reputation in Eighteenth-Century Britain.” Eighteenth-Century Life, vol. 36, no. 2, Spring 2012, pp. 111-142.

——. Curiosity: A Cultural History of Early-Modern Inquiry. Chicago UP, 2001.

——. “The Moral in the Material: Numismatics and Identity in Evelyn, Addison and Pope.” Arts in the Age of Queen Anne, edited by O.M. Brack and Cedric Reverand II, Bucknell University UP, pp. 65-83.

——. “Saying Things: Collecting Conflicts in Eighteenth-Century Objects Literatures.” Literature Compass, vol. 3/4, 2006, pp. 689-719.

Berg, Maxine, and Helen Clifford, editors. The Consumption of Culture, 1600-1800: Image, Object, Text. Routledge, 1995.

Birdsall, Virginia Ogden. Defoe’s Perpetual Seekers: A Study of the Major Fiction. Bucknell UP, 1985.

Blackwell, Mark, editor. The Secret Life of Things: Animals, Objects, and It Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England. Bucknell UP, 2006.

Brown, Bill. “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 28, no. 1, 2001, pp. 1-22.

Budd, Adam, editor. John Armstrong’s ‘The Art of Preserving Health’. Ashgate, 2011.

Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy, 6 vols., edited by Thomas C. Faulkner Nicholas K. Kiessling, and Rhonda L. Blair, Oxford UP, 1989-2000.

Defoe, Daniel. Robinson Crusoe. Edited by Michael Shinagel, W. W. Norton, 1995.

Delbourgo, James. Collecting the World: The Life and Curiosity of Hans Sloane. Penguin, 2017.

Fairer, David. “Persistence, Adaptation, and Transformations in Pastoral and Georgic Poetry.” The Cambridge History of English Literature, 1660-1780, edited by John Richetti, Cambridge UP, 2005, pp. 259-86.

Festa, Lynn M. Sentimental Figures of Empire in Eighteenth-Century Britain and France. Johns Hopkins UP, 2006.

Foucault, Michel. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, translated by Richard Howard, Vintage Books, 1964.

Hayden, Judy A. Introduction. Travel Narratives, the New Science, and Literary Discourse, 1569-1750, edited by Jody A. Hayden, Ashgate, 2012.

Hudson, Kenneth. Museums of Influence. Cambridge UP, 1987.

Hunter, J. Paul. The Reluctant Pilgrim: Defoe’s Emblematic Method and the Quest for Form. Johns Hopkins UP, 1966.

Impey, Oliver, and Arthur MacGregor, editors. The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Europe. Clarendon Press, 1985.

Jager, Eric. “The Parrot’s Voice: Language and the Self in Robinson Crusoe.” Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 21, no. 3, Spring 1988, pp. 316-333.

Kareem, Sarah Tindal. Eighteenth-Century Fiction and the Reinvention of Wonder. Oxford UP, 2014.

Koch, Philip. Solitude: A Philosophical Encounter. Open Court, 1994.

Kraft, Elizabeth. “The Revaluation of Literary Character: The Case of Crusoe.” South

Atlantic Review, vol. 72, no. 4, Fall 2007, pp. 37-58.

Lamb, Jonathan. “The Crying of Lost Things,” English Literary History, vol. 71, no. 2, 2004, pp. 949-67.

MacGregor, Arthur. Curiosity and Enlightenment: Collectors and Collections from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century. Yale UP, 2007.

McCracken, George. Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities. Indiana UP, 1988.

McKendrick, Neil, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb. The Birth of a Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England. Indiana UP, 1985.

McKeon, Michael. The Origins of the English Novel, 1600-1750. Johns Hopkins UP, 1987.

Novak, Maximillian E. Daniel Defoe: Master of Fictions. Oxford UP, 2001.

Pearce, Susan M. Museums, Objects and Collections: A Cultural Study. Leicester UP, 1992.

Pearl, Jason. “Desert Islands and Urban Solitudes in the Crusoe Trilogy.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 44, no. 2, Summer 2012, pp. 125-143.

Pope, Alexander. “Epistle V. To Mr. Addison, Occasioned by His Dialogue on Medals.” The Poems of Alexander Pope, edited by John Butt, Yale UP, 1966, 215.

Reid, Jennifer. Worse than Beasts: An Anatomy of Melancholy and the Literature of Travel. Davies, 2005.

Scott, Sir Walter. “Scott on Defoe’s life and works, 1810, 1817.” Daniel Defoe: The Critical Heritage, edited by Pat Rogers, Routledge, 1972, pp. 66-79.

Starr, George A. Defoe and Spiritual Autobiography. Princeton UP, 1965.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Johns Hopkins UP, 1984.

Svilpis, Janis. “Bourgeois Solitude in Robinson Crusoe.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 22:1, 1996, pp. 35-43.

Swados, Harvey. “Robinson Crusoe: The Man Alone.” Antioch Review, vol. 18, no. 1, Spring 1958, pp. 25-40.

Tobin, Beth Fowkes. Colonizing Nature: The Tropics in British Arts and Letters, 1760-1820. Pennsylvania State Press, 2005.

Wall, Cynthia. The Prose of Things: Transformations of Description in the Eighteenth Century. Chicago UP, 2006.

Walmsley, Peter. “Robinson Crusoe’s Canoes.” Eighteenth-Century Life, vol. 43, no. 1, January 2019, pp. 1-23.

Watt, Ian. The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. California UP, 1957.

Woodward, John. Brief Instructions. London: R. Wilkin, 1696.

Woolf, Virginia. “Robinson Crusoe.” The Second Common Reader. Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1932.