[T]he administration of the eighteenth-century criminal justice system created several interconnected spheres of contested judicial space in each of which deeply discretionary choices were made. Those accused of offences in the eighteenth century found themselves propelled on an often bewildering journey along a route which can best be compared to a corridor of connected rooms or stage sets. From each room one door led on towards eventual criminalization, conviction and punishment, but every room also had other exits. Each had doors indicating legally accepted ways in which the accused could get away from the arms of the law, while some rooms also had illegal tunnels through which the accused could sometimes escape to safety. Each room was also populated by a different and socially diverse group of men and women, whose assumptions, actions, and interactions, both with each other, and with the accused, determined whether or not he or she was shown to an exit or thrust on up the corridor.

Peter King, Crime, Justice and Discretion in England, 1740–1820

THIS ESSAY describes the journey of Daniel Defoe’s first fictional thief through the “interconnected spheres” of the criminal justice system of her time, following her route along Peter King’s “corridor of connected rooms or stage sets,” from the moment of her arrest, through committal to prison by a Justice of the Peace, to a Grand Jury hearing, arraignment, trial, sentencing and beyond. In each of these rooms, Moll Flanders has to negotiate with men and women from various social backgrounds, each of them empowered to make “deeply discretionary choices”; she makes repeated attempts to escape, now through doors offering officially accepted ways out, now through “illegal tunnels,” only to find herself thrust on up the corridor toward “criminalization, conviction and punishment” (King 1-2).

The route is not always clearly posted, and the rules and customs that govern these “judicial spaces” are very different from those that apply in the English system of justice as it has evolved over the last three hundred years, so that this journey is often more bewildering to the modern reader than it is to Moll. In trying to illuminate her way I have drawn heavily on the work of social historians, but also, for closer focus on the experience of actually existing people who resemble Moll, her allies and opponents, on reports of thirty-four trials in which thirty-seven men and women were charged at the Old Bailey with stealing from shops during the two years leading up to the publication of Moll Flanders in January 1722.[1]

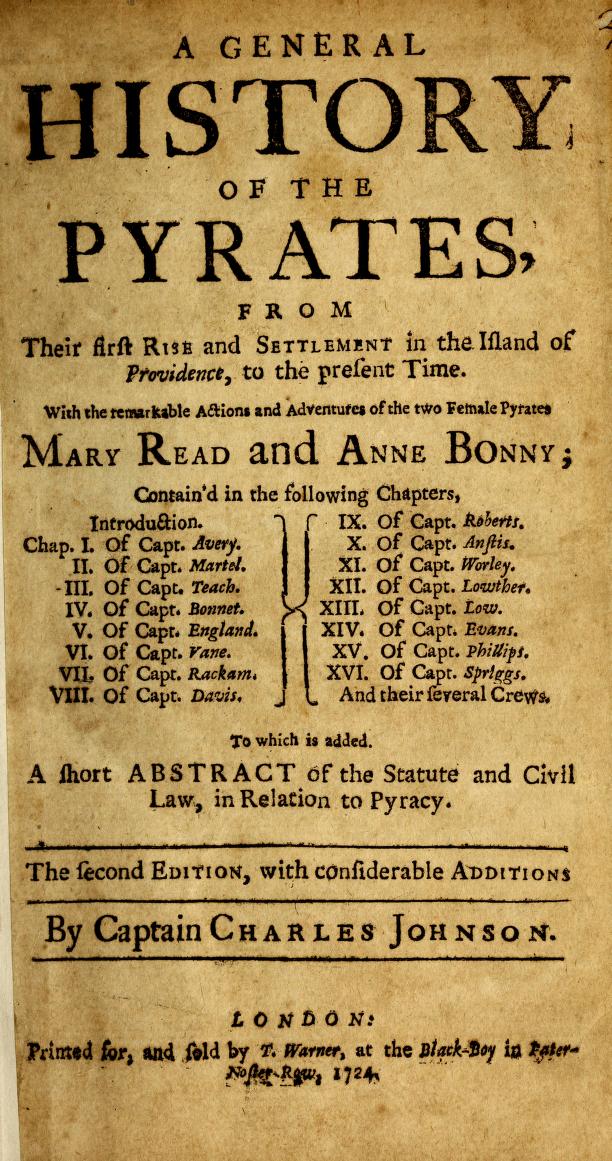

As historical records, the Old Bailey Proceedings, thankfully digitalized and searchable, are unreliable in various ways. They give more coverage to sensational cases than to the humdrum non-violent property offences which made up the bulk of prosecuted crime; until 1729 they omit or summarize briefly much of the testimony, often ignoring defense evidence in favor of that brought by the prosecution (Shoemaker, “The Old Bailey Proceedings” 567-68). They nonetheless tell us a good deal about what was said in eighteenth-century courtrooms, and offer many clues as to how the speakers came to be there. Defoe could easily have heard their words for himself by joining the crowds in the Sessions House Yard, and in these years of intense journalistic activity would have known—even if he did not write all those once attributed to him—the stream of crime reports appearing in newspapers such as Applebee’s Weekly Journal, in the chaplain of Newgate’s Accounts of the lives and last days of those condemned to die (also published by Applebee during these years), and in biographies and volumes of select trials. Of these, the Proceedings, by the terms of its license obliged to report all trials, may have been the most helpful to a writer trying to tell convincing fictional lives of thieves in 1720s London, and their popularity makes them an excellent source for understanding the expectations of his early readers.[2] By comparing Defoe’s narrative of prosecution with the patterns that emerge from these reports, we can see which possibilities he chose to develop, which to ignore and which to flout, and we may also make hypotheses about why he made those choices.

1. Fear of Witnesses

Besides justice, judge, grand and petty jury, the main actors in the prosecution and trial of Moll Flanders consist of Moll herself, the prosecutor (a broker in the cloth trade we come to know as Anthony Johnson), and the broker’s two maid-servants. Moll would have not felt out of place among the flesh-and-blood defendants at the Old Bailey in the early eighteenth century, and readers of the Proceedings would not have been surprised to read of Defoe’s supposedly destitute protagonist having taken to shop-lifting. In the course of the seventeenth century shops had come to replace the fair and the market as channels for distributing all goods but trifles and fresh food (Mui and Mui 27), and as the retail trade responded to the growth of the wealthy middling sort of consumer and the demand for leisure shopping, the new, brightly-lit windows for displaying goods, and the counters over which shopkeepers and their assistants negotiated with customers, offered new opportunities for privately stealing.[3] The last decades of the seventeenth century and first of the eighteenth saw dramatic growth in prosecutions of women in general, and especially for shop-lifting, which had been made a capital offence in 1699 (Beattie, Policing and Punishment 63-71). Of the thirty-seven prisoners in my 1720-1721 sample, fifteen were women, and though this figure falls short of the 51.2% peak reached between 1691 and 1713, Proceedings readers would have recognized in Moll a familiar figure, a plebeian woman’s voice of a kind they had become accustomed to hearing (Shoemaker, “Print and the Female Voice” 75).

Johnson and his maids too would have found themselves at home among those who denounced property crime in eighteenth-century courts of justice. In both Essex (King 35–42) and Surrey (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 192-97), and probably in London as well, most prosecutors belonged to middling and lower social groups: tradesmen, dealers, craftsmen, unskilled labourers, servants, and even paupers. The majority were the victims of the thefts, and their witnesses were usually members of their households (including servants and apprentices), neighbors or fellow traders. Almost invariably these people owed their knowledge of the crime to having personally taken part in apprehending the accused. Early modern England usually left it up to private citizens to take the initiative in law enforcement. Many must have decided not to tackle, report or try to trace a suspect; others seem to have done so enthusiastically (Beattie, Policing and Punishment 30, 50-55; Shoemaker, The London Mob 28-30). Some of the willing may have had venal motives. Victims often paid to get their property back, and though the huge statutory rewards for successful convictions of highway robbers, burglars, coiners and so on did not extend to shoplifters, since 1699 prosecutors of these thieves too had been entitled to a ‘Tyburn Ticket,’ an exemption for life from parish and ward office highly valued by middling-sort Londoners (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 52, 317, 330). Many, however, would have acted out of “pure outrage at being robbed”; Beattie suggests that “broad agreement about the law and about the wickedness of theft or robbery helps to explain the spontaneous character of many arrests in the eighteenth century and the willingness of large numbers of ordinary people to lend a hand” (Crime and the Courts 37).

If we have no way of knowing exactly why particular people arrested suspects, we can learn a good deal from the Proceedings about how they came to do so. Of the thirty-seven men and women in my sample, seven were acquitted.[4] Except in the case of Elizabeth Simpson, the Proceedings gives no details about how these verdicts were reached, referring merely to “the Evidence not being sufficient.” In seven further cases in which the prisoner was found guilty, the reporter is equally unforthcoming, stating only that “[i]t appeared that” the prisoner had taken the goods, that “The Fact” was “plainly prov’d upon him,” or that the prisoner had confessed before a justice.[5] In the remaining twenty-three, however, the Proceedings makes it plain that the thief has been caught in one of three, or possibly four, ways. They are either taken by someone present at the scene of the crime, or reported “after the Fact” by an intermediary to whom they have tried to sell the stolen goods, or shopped by an accomplice, or seized by a professional thief-taker.

Most frequently, some person on the spot sees or hears something suspicious, or quickly misses the goods, seizes and searches, or follows a suspect through the streets, perhaps involving others in a chase. We do not always know who this person is. About the “two Evidences” who saw Susannah Lloyd take a checked tablecloth off Nathaniel Clark’s shop counter, the Proceedings tell us nothing (t17200303-38). In several instances, witnesses are identified as members of the prosecutor’s family, usually a wife or daughter responsible for running and guarding the shop. When John Jackson prosecuted Edward Corder, the chief witness was an Elizabeth Jackson who “was sitting in a back Room, about 7 at Night” when she heard someone open a drawer, “ran out and stopt the Prisoner in the Shop, with the Goods upon him, till some others came to her Assistance” (t17211206-6). The wife of prosecutor Robert Fenwick was “in her Parlour behind the Shop” when Mary Hughes came in, but did not tackle the thief in person: “she … saw the Prisoner take the Goods and immediately sent her Servant after her” (t17200115-40). In another case (t17211011-5), Mrs Elson, wife of the prosecutor, was positive that she had seen Thomas Rice put some lace “in his Bosom and run away with it”; she had him followed and searched, but the lace was not found. As long as he or she was inside the shop, a thief could still claim to be a bona fide customer, but once outside he or she could get rid of the goods more easily, so the timing of an arrest was important. Mary Leighton claimed to have seen Margaret Townley take ribbon from her mother’s shop, “let her go out of the Shop a good way, and then sent to fetch her back again, that when she was brought back she searcht her” (t17200712-4).

Shop security was clearly one of the key functions of employees (Tickell 304). In some of the above cases servants, perhaps apprentices or journeymen, were called on by masters and mistress to catch thieves; in others they acted independently. James Bartley, servant to a draper, told how he suspected Mary Atkins, followed her down the street and found some muslin under her cloak (t17210525-38). John Goodchild’s servant carefully orchestrated the arrest of Katherine Crompton; seeing her take a piece of muslin, he “called the Maid down Stairs” before searching her, and made sure that Goodchild himself and one Jane Ballard would be able to confirm his testimony (t17200907-30).[6]

Jane Ballard may have been a customer who just happened to be in the shop at the time of the theft, as perhaps was Joseph Lock, the alert and fast-acting apprehender of John Scoon. Lock, “being in the Prosecutors Shop” heard the display case rattling, stepped to the door, “saw the Prisoner at the Glass Case, and stopt him”; he then, “charg’d a Constable with the Prisoner, and search’d him. and after some time the Prisoner gave’em the Chain from the Wastband of his Breeches” (t17211206-3). In another case a neighbour, Joseph Austin, found Mary North standing behind the door into his house and claimed to have allowed her in to hide from bailiffs; later, “hearing the Prosecutor was robb’d, followed, took and carried her to him and saw the Goods in her lap” (t17200303-10).

In other cases casual passers-by seem to have been keen to have a go (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 226-58). At David Pritchard’s trial, William Dunkley deposed that he had noticed Isaac Johnson standing at the end of a street, and asked him what he was doing; Johnson replied that he had “observed the Prisoner lurking about, and suspected that he had a Design against the Prosecutor’s Shop.” When Pritchard reached into the shop and took the goods, Johnson chased and seized him; Dunkley too gave chase, but a coach got in his way and by the time he caught up, Johnson “was scuffling with the Prisoner on the Ground with the Goods under him” (t17210830-18).

This testimony rings a little odd. Had Johnson been following Pritchard in the hope of a prize? Were Dunkley and Johnson collaborating, or were they competing to get their hands on the thief? Was either or both of them one of the professional thief-takers who proliferated in these years? If either Johnson or Dunkley—or both—were thief-takers, we must add private enterprise to the methods by which my cohort of thieves were caught.

Strangely, dealers in blood-money do not figure among the antagonists of either Moll Flanders, or even Colonel Jack and the footpads and burglars with whom he associates, and who were the favorite targets of thief-takers. Defoe may have been reluctant to highlight mercenary motives for taking an active part in law enforcement.[7] Moll and her kind fear being taken at or near the scene of their crimes not by professionals but by members of the business community on which they prey. Moll’s first “Teacher” is “snap’d by a Hawks-ey’d Journey-man,” prosecuted, and sent to the gallows (203-04). When Moll takes some damask from a shop and passes it to an accomplice, the latter is seized by the mercer’s men, and Moll, half- relieved, half-terrified, sees “the poor Creature drag’d away in Triumph to the Justice, who immediately committed her to Newgate” (221). Her next partner, a “rash” young man, is taken by a furious crowd and ends up on the gallows; she too is run to ground and only narrowly avoids being arrested (216-17). On another occasion Moll is seized by a pair of mercer’s journeymen (241), and on yet another by an “officious Fellow” who has noticed her enter a silver-smith’s shop in the absence of the owner (269).[8]

In all these episodes those who arrest Moll or her comrades are presented as vigilant, quick-acting and aggressive. The two maids who put an end to her thieving career are no exception. Moll has ventured through an open door and “furnish’d myself as I thought verily without being perceiv’d, with two Peices [sic] of flower’d Silk, such as they call Brocaded Silk, very rich” when she is rudely interrupted:

I was attack’d by two Wenches that came open Mouth’d at me just as I was going out at the Door, and one of them pull’ me back into the Room, while the other shut the Door upon me; I would have given them good Words, but there was no room for it; two fiery Dragons cou’d not have been more furious than they were; they tore my Cloths, bully’d and roar’d as if they would have murther’d me … (272)

Moll is thus trapped in the first of Peter King’s judicial spaces, that of the arrest, and it is the worse for her that it is populated by plebeian women who have no time for “good Words,” or good manners. The two “Wenches,” with their open mouths, rough hands and loud voices, “attack” and “pull,” tear, bully and roar in thoroughly unlady-like manner. We shall hear more of their murderous roaring, for the progress of Moll Flanders through the judicial process will be determined largely by what these “fiery dragons” do and say.

Not involved in person in Moll’s story, but very present in her mind, is another, more insidiously menacing type of witness. In three of my Old Bailey trials, the prosecution case relies on the testimony of an associate or accomplice. Henry Emmery was reported for stealing pistols by “the Father of a Woman whom the Prisoner kept,” and “betrayed” also by the woman herself for taking weights from the very pawnbroker to whom he had pawned the pistols (t17200907-16). Robert Lockey asked a fellow journeyman named Vaughan to sell three dozen sword blades he had taken from their master’s shop; Vaughan “confest the Matter” before a justice, after which each accused the other of having “enticed him to do it” (t17210830-3). A simpler story is that of Ruth Jones; taken with a skin of leather under her petticoats, Jones accused Mary Yeomans of having “[given] her the Leather and bid her go away with it” (t17210525-14).

Inducements to finger a partner in crime in early eighteenth-century England were enormous. By turning crown witness an accomplice could avoid prosecution and save his or her own neck, perhaps becoming eligible for a reward (Langbein 158-65). No fellow thief informs on Moll, but not for want of trying: at one point the whole of Newgate is threatening to impeach her (214). Luckily she has never let anyone “know who I was, or where I Lodg’d” (221), but the psychological cost of deliberate anomie, and of the homicidal desires induced by fear, comes out in two of the darkest episodes in the novel. The rash young man gets “his Indictment deferr’d, upon promise to discover his Accomplices” (218), and though he fails to track Moll in time, she goes into hiding and remains under “horrible Apprehensions,” until she receives “the joyful News that he was hang’d” (220). The “Comrade” to whom Moll passes the mercer’s goods is similarly unable to “produce” or “give the least Account” of her accomplice, but the court, considering her “an inferiour Assistant … allow’d her to be Transported.” At once “troubled … exceedingly” for this “poor Woman,” yet anxious lest she manage to buy a full pardon at her expense, Moll is not at peace until her partner has been shipped to Virginia. Indeed Defoe’s protagonist is only “easie, as to the Fear of Witnesses against me” when “all those, that had either been concern’d with me, or that knew me by the Name of Moll Flanders, were either hang’d or Transported” (222-23).

Another type of witness is absent from her story. Many shopkeepers, dealers, and pawnbrokers in eighteenth-century London were happy to buy goods cheaply without asking too many questions. We find few traces of such people in the Proceedings, unless—as in the case of Elizabeth Pool (t17200115-34)—they were indicted for receiving. An exception is “one Beachcrest, a Slopseller at Billingsgate,” who bid Anne Nicholls “bring any thing she could get to him, and he would give her Money for it” (t17211206-2). Law-abiding intermediaries who reported suspicious offers are, for obvious reasons, more visible. Among those in my sample is a Mr Baker, a bookseller who noticed, from the way the titles were pasted into the three books James Codner had sold him, that they must have come from a fellow dealer, and sent to Gustavus Hacker “to know if they had lost such Books” (t17201207-12). A wigmaker who became suspicious when John Cauthrey was willing to take fifteen shillings for a two-guinea wig sent “to enquire after his Character” (t17210525-28). Another wig-thief, Edward Preston, was “taken offering them to Sale” (t17200907-29). When Hannah Conner brought a silver mug to John Braithwait to be weighed, he questioned her persistently until she “at last owned she stole it out of the Prosecutor’s Shop in Canon Street” (t17201207-6). Samuel Dickens had not even noticed that “a Camblet Riding-Hood and 14 Yards of Persian Silk” had gone missing from his shop until a pawnbroker arrived and brought him to Elizabeth Pool, who admitted to having had them from Richard Evans (t17200115-34).

In certain cases, victims went to great trouble to nail a thief, mobilizing numbers of neighbors, intermediaries and artisans. John Everingham, clearly exasperated at having “lost a great quantity of Twist at several times,” got his chance to track Alice Jones down when “one of his Neighbours seeing some of his Goods in Mr. Crouch’s Shop, acquainted him with it.” Everingham found the twist at Crouch’s, followed the trail back through another dealer named Hall, and from Hall to a Mr Rawlinstone, on whose premises he was lucky enough to find “the Prisoner there offering more Goods to sale.” Not content with Jones’s confession before a Justice, plus the testimony of the three intermediaries, Etherington went on to consolidate his case by looking out two artisans who had worked the twist specifically for him (t17200303-4).

No one resembling John Braithwait, Mr Baker or Cauthrey’s wig-maker feature in Moll Flanders. Early on in her criminal career Defoe solves Moll’s marketing difficulties once and for all by providing her with an efficient, generous and devoted fence. Having accumulated a quantity of luxury pickings, she finds out her old friend and “Governess,” the woman who had helped her last lying-in. This resourceful businesswoman has in the meantime conveniently “turn’d Pawn-Broker”—and something more (197-200): receiver, teacher and organizer of a small army of burglars, shoplifters and pickpockets, she closely resembles a character whose shadow has already fallen on our story—that of Jonathan Wild. Luckily for Moll, her governess does not seem to have included informing or thief-taking among her many sources of income; at least in the case of her favorite pupil she will go to great lengths to save her from the gallows. Critics have noticed the maternal role of this and other women in the novel (Chaber 220; Swaminathan 195), but in the world of Moll Flanders any “female support system” cannot but be fragile. When threatened with the gallows the women, like the men, try to send others in their places. Some, as we shall now see, seem strangely determined to watch Moll die for no apparent reason.

2. In the Justice’s Parlour

Those who apprehended thieves in eighteenth-century England did not always march them off to a Justice of the Peace. As with detection and arrest, it was up to private individuals to start the judicial machine rolling. Many chose to let the matter drop, perhaps exacting an apology, informal punishment or compensation. There were strong disincentives to prosecution: costs in time and money, fear of retaliation or unpopularity, and, as in the case of the “Mistress of the House” in Moll’s case, pity. The size of the ‘dark figure’ of unprosecuted crime is by definition a mystery, but in the eighteenth century it was probably “immense” compared to the “tiny but brightly illuminated figure of the indicted” (King 30-32, 132). If Moll now tries to negotiate with her potential prosecutors, it is because she knows that they can, if they wish, let her slip out of the spotlight:

I GAVE the Master very good Words, told him the Door was open, and things were a Temptation to me, that I was poor, and distress’d, and Poverty was what many could not resist, and beg’d him with Tears to have pity on me; the Mistress of the House was mov’d with Compassion, and enclin’d to have let me go, and had almost perswaded her Husband to it also… (272-73)

In begging for mercy, she is running a risk. When Mary Leighton found some of her mother’s ribbon in Margaret Townley’s pocket, Townley “fell down on her Knees and begg’d pardon,” only to have this recounted in court as evidence of guilt (t17200712-4). In Moll’s case the move nearly pays off. The Master is about to capitulate when he is prevented by the fait accompli of his tough and independent-minded maids: “the saucy Wenches were run even before they were sent, and had fetch’d a Constable, and then the Master said he could not go back, I must go before a Justice, and answer’d his Wife that he might come into Trouble himself if he should let me go” (273). What kind of “Trouble” this broker might have got into is not clear, but he shows a consistent tendency to defer to authority. Now, as “[t]he sight of the Constable” sends Moll “into faintings” (274), discretionary power slips through the master’s fingers.

The mistress, on the other hand, proves a stalwart ally. She “argued for me again, and entreated her Husband, seeing that they had lost nothing to let me go,” a pragmatic consideration to which Moll adds an appeal to self-interest: “I offer’d him to pay for the two Peices whatever the value was, tho’ I had not got them, and argued that as he had his Goods, and had really lost nothing, it would be cruel to pursue me to Death, and have my Blood for the bare Attempt of taking them” (273). This offer to pay for goods “not got” constitutes an invitation to “turn a theft into a purchase,” an illegal way out of the judicial corridor, but one probably used frequently (Tickell 307). The journeyman John Cauthrey (t17210525-28) hoped to be able to “make a debt of it” when confronted by his master with having stolen wigs from his shop. In law the fact of having “lost nothing” was not supposed to exempt from punishment: Giles Jacob’s A New Law Dictionary of 1729 (qtd. by Starr 392n.) defined all offences in terms of “Intent to commit some Felony, whether the intent be executed or not.” Among my Old Bailey accused there are, however, none arraigned for intending to steal; Moll astutely reminds mistress, master, constable and then justice, that she had not “carried any thing away.”

She also stresses that she “had broke no Doors,” a circumstance which should have saved her from being charged with house-breaking in the presence of the owners, an offence regarded seriously for involving violation of private property and “putting in fear.” Moll is well-informed on legal technicalities (Swan 150-57)—but also on discrepancies between theory and practise. Jacob declared house-breaking to include lifting up a latch on the way out (qtd. by Starr 382n.); but how many were actually charged on that basis? Moll’s defence seems to have persuaded not only Mistress and Master, but even the Justice himself, now “enclin’d to have releas’d me.” Then, once again, her escape hatch is slammed shut by the maids, one of whom now firmly takes the lead: “the first saucy Jade that stop’d me, affirming that I was going out with the Goods, but that she stop’d me and pull’d me back as I was upon the Threshold, the Justice upon that point committed me, and I was carried to Newgate; that horrid Place!” (273). How Moll’s hearing before this justice compares with those experienced by my contingent of real shoplifters is hard to deduce from the Proceedings, except in one respect. Moll’s persistence in defending herself distinguishes her from ten in my sample who confessed before magistrates.[9] James Codner seems to have hoped to earn “Favour” by so doing (t17201207-12). Hannah Conner and Richard Evans must have regretted having given way; when their confessions were read in court they retracted, but were found guilty nonetheless (t17201207-6). In obtaining confessions justicial hearings fulfilled the official function of the pre-trial procedure as described by Langbein: that of helping make the strongest possible prosecution case and thus reinforce the citizen’s role in law enforcement (40-43). The magistrate was meant by law to “take examination of such Prisoner, and information of those that bring him, of the fact and circumstance … as much thereof as shall be material to prove the felony” (2&3 Phil & Mar., c.10, qtd. in Langbein 41).

These hard-line instructions were, however, contested by commentators as authoritative as Blackstone, and contradicted by recommendations that magistrates act as peace-makers in the community; in practice they were often ignored (King 88-93). Beattie has shown that, in London especially, the nature of the preliminary hearing was changing, allowing more accused felons to be released (Policing and Punishment 106). Rather than send cases on for trial, magistrates could choose one of four options, three of which would have been available in a case like Moll’s.[10] Her J.P. could have treated her offence as a minor one, such as trespass, and used his summary powers relating to vagrancy and the disorderly poor to commit her to a house of correction and whipping (King 132).[11] Alternatively he could have mediated a settlement between victim and accused; Anthony Johnson has refused Moll’s offer of payment, but might have given way if encouraged to be lenient by an authority. The last option, that of discharging the accused for want of evidence, came to be used commonly later in the eighteenth century, especially by energetic investigators like the Fieldings, and under pressure from the attorneys who took an increasing part in pre-trial hearings. In Defoe’s time this was rare, however, and according to Beattie, impossible when a witness swore to a felony charge. By “affirming that I was going out with the goods,” number one “saucy jade” has taken control, leaving the magistrate with little choice but to push Moll “on up the corridor” toward Newgate, the Old Bailey and Tyburn. His clerk would have taken down the testimony of accuser and accused, ‘freezing’ the evidence in the form of written depositions which would be handed in when the assizes were convened at the Old Bailey. For the interval the magistrate would bind over prosecutors and their witnesses on pain of £40 penalties designed to ensure that they did not change their minds about testifying, and commit the accused to gaol to prevent her from absconding (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 269-74, 281).

3. Tampering with the Evidence

This is precisely what happens to Moll. Back in the prison where she was born, accused of a crime remarkably similar to her mother’s “borrowing three pieces of fine Holland, of a certain draper in Cheapside” (8), she comments wryly: “I was now fix’d indeed.” Over the coming weeks the prosecutor will remain free to strengthen his case, perhaps persuading witnesses to testify to fact, or to the ownership of the property stolen. It would have been during this interval, presumably, that John Everingham sought out his twist-makers, while Alice Jones would have remained locked up, reliant on the advice of fellow jailbirds, ‘Newgate Attorneys,’ and visiting friends for help in preparing to face her accusers (t17200303-4).

In theory, those charged with felonies in eighteenth-century England were not meant to prepare for trial at all, since spontaneity was supposed to allow juries a clear perception of guilt or innocence. But the Proceedings give us clues as to how prisoners might get some sort of defence together (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 441-46; King 230). At her trial Margaret Elson (t17201207-9) “called one to prove” her explanation of why she had been in a coach with John Abraham and a stolen 108lb mortar; she must have got word to this person from Newgate. She is the only one to have sought a witness to fact; most had to fall back on testimony to reputation, which was thought important. James Cawthrey had offered the man guarding him five shillings for “a good Character” (t17210525-28).

Cawthrey’s offer was rejected, but eight of my sample found several each to speak for them.[12] Only in the two cases in which insanity was pleaded does the Proceedings tell us what these witnesses actually said in court. Of Mary North one “said he believ’d her Lunatick … Another who deposed that she had 700 l. to her Portion, but marryed an ill Husband who had brought her very low, and believed this to be her first Fact” (t17200303-10). On behalf of James Codner a Mrs. Harris stated that she “had known him from a Child,” and a Mrs. Simpson, who “knew him well,” also “observed him to be out of his Senses for Two Months before this matter happen’d and that he was a sober good Man before.” Insanity pleas tended to be successful with judges and juries, and the word of established neighbours and of employers was especially persuasive (King 304, 309). Codner’s Master deposed

that he found him disorder’d in his Mind, and that he was forcd for 2 Months before this Fact to employ another in his Room; that he let him come to him however, and imployed him in some little matters now and then; that before his Disorder he found him very Honest having entrusted him frequently. (t17201207-12)

How influential was character testimony in general? The Proceedings reporter tends to note its absence in negative terms. Mary Hughes had “none to her reputation,” and was condemned to death (t17200115-40). On the other hand, both Edward Preston (t1720907-29) and Alice Jones (17200303-4), neither of whom called any witnesses, received the lighter sentence of transportation. To some, character witnesses seem to have done no good at all. Katherine Crompton “called several to her Reputation: but the Evidence being very full, the Jury found her Guilty. Death.” Hannah Conner’s trial, reported in almost identical terms, ended with a death sentence, though she was subsequently respited for pregnancy. Margaret Elson and Elizabeth Simpson are the only accused in my sample to have been fully acquitted on the basis of defense testimony. In other cases a good character may have helped mitigate verdicts, or influence judges favorably. The receiver Elizabeth Pool was found guilty for a lesser offence and transported, while the man with whom she was tried, Richard Evans, had his death sentence respited on condition of undergoing experimental inoculation for smallpox. Codner, so strongly supported by neighbours and Master, got away with being burnt in the hand. The “26 Ells of Dowlas Cloth. value 33 s.” taken by Mary North was down-valued by the jury to 4s.10d, which saved her from a death sentence, while David Pritchard’s 28 yards of crape were valued at only 10d, letting him off with a whipping.

Moll might have hoped for a similar sentence, but for the fact that she has “no Friends” (281), certainly none likely to make a good impression in court. Her Governess is an underworld habitué who has quite other ideas about the “proper methods” of getting people off the judicial hook:

first she found out the two fiery Jades that had surpriz’d me; she tamper’d with them, persuad’d them, offer’d them Money, and in a Word, try’d all imaginable ways to prevent a Prosecution; she offer’d one of the Wenches 100 l. to go away from her Mistress, and not to appear against me; but she was so resolute, that tho’ she was but a Servant-Maid at 3 l a Year Wages or thereabouts, she refus’d it, and would have refus’d it, as my Governess said she believ’d, if she had offer’d her 500 l. Then she attack’d the tother Maid, she was not so hard-Hearted as the other; and sometimes seem’d inclin’d to be merciful; but the first Wench kept her up, and chang’d her Mind, and would not so much as let my Governess talk with her, but threaten’d to have her up for Tampering with the Evidence. (276-77)

One of the “illegal tunnels” out of Peter King’s judicial corridor, tampering with the evidence, which in theory included any kind of endeavour to dissuade a witness, was punishable by imprisonment and a large fine (Jacob, qtd. by Starr 390n), so it is not surprising that the Governess desists when threatened with being ‘had up.’ Less comprehensible is the iron resolution of a maid-servant who refuses the equivalent of thirty-three years’ wages rather than let an unsuccessful thief go free. Defoe never has Moll even hint at why this woman is so adamant. There is no mention of rewards, but nor is it suggested that she is driven by a sense of public service or reforming zeal. She could hardly have been impelled by a desire to please her employers, who are at best lukewarm about this prosecution.

Even now, the mistress continues to argue in Moll’s favour, and though her husband rejects the Governess’s blandishments, it is for a puzzling mix of reasons:

the Man alledg’d he was bound by the Justice that committed me, to Prosecute, and that he should forfeit his Recognizance.

My Governess offer’d to find Friends that should get his Recognizances off of the File, as they call it, and that he should not suffer; but it was not possible to Convince him, that could be done, or that he could be safe any way in the World, but by appearing against me. (277)

Seemingly unconcerned about the ethics of getting recognizances “off of the File,” this prosecutor worries only that the Governess’s “Friends” (presumably malleable clerks to the court) will not succeed, and that he will be left out of pocket. It is true that the sum he would have pledged at Moll’s pre-trial hearing could have been huge (£120, £40 each for himself and the two maids), though King finds that courts were lenient about enforcing such payments; one in ten of his sample prosecutors dropped out before the trial (43-44). In my Old Bailey sample only Daniel Veal (for his second indictment, t17211206-76) was acquitted because “no Evidence” appeared against him—but then the Old Bailey seems to have been trying to stamp down on “no shows” at this time. On December 6, 1721, while Defoe would still have been at work on Moll Flanders, the bench ordered that “All Persons that have not attended the Court in the Trials of those Prisoner [sic] whom they were bound to Prosecute, are to have their Recognizances Estreate” (s17211206-1).

With the failure of her Governess’s efforts to buy off the prosecution, Moll begins to lose hope: “so I was to have three Witnesses of Fact against me, the Master and his two Maids, that is to say I was as certain to be cast for my Life as I was certain that I was alive” (277). Against “three Witnesses of Fact,” she assumes that she has no chance: “I had a Crime charg’d on me, the Punishment of which was Death by our Law; the Proof was so Evident, that there was no room for me so much as to plead not Guilty; I had the Name of a Old Offender, so that I had nothing to expect but Death in a few Weeks time …” (278-79). Early readers acquainted with the procedures by which “our Law” was applied would have known that Moll’s fate is not yet sealed. She does not yet know what offence she will be charged with in court—it could yet be the non-capital crime of petty larceny[13]—nor is it clear that the “Name of an old Offender” has in fact caught up with her, or indeed under what name she is being prosecuted (Gladfelder 129). Moll has now has taken yet another step along Peter King’s grim corridor, but she has by no means passed all the possible exits to safety.

4. A Plain Case?

First among these, that “Proof” Moll labels “Evident” has yet to be vetted by a grand jury. Throughout the eighteenth century grand juries continued to play an important role in filtering out weak and malicious prosecutions (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 318-19). This body of twenty or so men of property, most of them experienced jurymen and many themselves magistrates, must now hear the sworn testimony of Johnson and his maids, and either find the bill of indictment “vera,” sending Moll to trial, or “ignoramus,” in which latter case she will be discharged.

Grand jury verdicts were not foregone conclusions: a surprising number of bills were thrown out (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 403). Their deliberations remain “shrouded in mystery,” but they would have been influenced by factors such as how seriously they considered the offence, perceptions of the state of crime and of economic conditions, and any prior knowledge of the offender (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 327; King 221). No defence testimony will be heard however, so Defoe’s early readers would have understood why Moll’s indefatigable Governess now goes to work behind the scenes: “a true Friend, she left me no Stone unturn’d to prevent the Grand Jury finding [the Bill and finding] out one or two of the Jury Men, talk’d with them, and endeavour’d to possess them with favourable Dispositions, on Account that nothing was taken away, and no House broken, etc.” (282).[14] Again the usual arguments seem about to succeed, but again crumble in the face of direct testimony: “all would not do, they were over-ruled by the rest, the two Wenches swore home to the Fact, and the Jury found the Bill against me for Robbery and Housebreaking, that is, for Felony and Burglary” (282). For the third time the maids succeed in slamming shut a door to safety. One of Moll’s keepers reports the Newgate consensus as to her prospects: “They say, added he, your Case is very plain, and that the Witnesses swear so home against you, there will be no standing it … indeed, Mrs. Flanders, unless you have very good Friends, you are no Woman for this World.”

Yet is this case so “very plain”? Howard Koonce has accused Moll of getting in a muddle, but she is not the only one who seems confused here. The bill of indictment seems to equate the usually violent crime of “robbery” with the generic “felony,” and “house-breaking” (a day-time crime) with the more serious night crime of “burglary.” As to house-breaking, Moll has always insisted that she had entered through an open door, and was leaving the same way, so that we do not expect such a charge, even as so broadly defined by Giles Jacob’s Dictionary. Blackstone was to complain about lack of clarity in the concept of burglary (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 162): should we attribute the unclear wording of this indictment to a general legal haziness, or is Defoe telling us that Johnson deliberately opted for the tougher charges—and if so why? Surely not under the influence of his maid, however fiery? Could it be the Grand Jury which has introduced the muddle? Has Defoe deliberately entangled the matter, and does he expect his readers to notice?

The Proceedings are of no help to us here, for they do not specify under which statute a prisoner is being charged. But Moll’s prosecutor, or someone, does seem to have over-reached himself here—or so Moll sees it, we may deduce from the manner in which, after many weeks in prison, she faces her accusers in the most public of judicial spaces.

5. Moll Speaks

First her arraignment, the day before the trial. Only now, and in accordance with the practice of not allowing the accused time to prepare a story for the jury, is Moll told the precise charge against her: “I was indicted for Felony and Burglary; that is, for feloniously stealing two Pieces of Brocaded Silk, value 46 l., the goods of Anthony Johnson, and for breaking open his Doors” (284). To this she has no hesitation about pleading “not Guilty, and well I might … I knew very well they could not pretend to prove I had broken up the Doors, or so much as lifted up a Latch” (284).

Moll’s self-confidence sets the tone for her comportment in court next day. The format for her trial is quite unlike that of the modern adversarial stand-off between professional barristers, in which accused and judge speak hardly at all, in which evidence is highly-regulated, and defendant presumed innocent until proved guilty beyond reasonable doubt. In the ‘accused speaks’ trial described by Langbein (48-61), the prisoner was meant to address the jury directly and spontaneously, conveying as much by his or her aspect and manner as by his or her words. Expected to challenge the prosecutor’s version of what happened and, if innocent, be able to explain to the satisfaction of the jury how he or she came to be involved, defendants could call witnesses, but they testified unsworn, and counsel was not permitted: legal learning and studied eloquence would supposedly obscure a jury’s unmediated perception of the naked truth.

So much for the theory. In practice, Beattie suggests, most of the accused were men and women

not used to speaking in public who suddenly found themselves thrust into the limelight before an audience in an unfamiliar setting—and who were for the most part dirty, underfed, and surely often ill—did not usually cross-examine vigorously or challenge the evidence presented against them. (Crime and the Courts 50-51)

The impression we gain from Proceedings reports of 1720-21 shoplifting trials is fairly consistent with Beattie’s little sketch. Alice Jones, Henry Emmery, and Edward Preston are all said to have had “nothing to say” for themselves (t17200303-4; t17200907-16; t17200907-29). Katherine Crompton merely “denied the Fact” (t17200907-30); Mary Hughes “had nothing to say in her Defence but a bare denial of the Fact” (t17200115-40); and Richard Evans denied everything, including his confession: “he did not know what he said before the Justice” (t17200115-34).

The Proceedings reporter evidently construed having “nothing to say” as evidence of guilt, and perhaps juries did also. No wonder most prisoners did try to say something. Edward Corder, rather feebly, “laid in his Defence, that he was Drunk, and knew not what he did” (t17211206-6). Others offered an alternative version of events, but it is they who would have borne the burden of proof, and few of their stories were believed. John Abraham pleaded that he had had his huge mortar “of a Gentleman out of the Country, who desired him to sell it for him; but could not prove it” (17201207). Hannah Conner had confessed to stealing a silver mug, but “on her Tryal denied that she stole it, saying as at first, that a Man desired her to weigh it for him, (but could not prove it)” (t17201207-6). John Scoon “in his Defence laid he won the Chain at Southwark Fair, but could bring no proof of it” (t17211206-3). Mary Atkins, perhaps more plausibly, claimed that James Bartley, the servant who had followed and searched her, “had been in her Company several times, asked her to come to him and he would give her something, pay his Master for it; that accordingly she went, and he gave her the Goods she was now charged with”; but then, having “called none to prove it,” she was found guilty (t17210525-38). The only accused who seems to have convinced the jury (and reporter) is Elizabeth Simpson who, besides calling several to give her a “very good character,” gave a detailed account of her shopping expedition with Ruth Jones; unlike Jones, who had little to say for herself, Simpson was acquitted (t17200115-3).

How does Moll’s behaviour at the bar compare with that of her flesh-and-blood counterparts? Like them, she has no counsel; unlike many, she has no character witness either. As for speaking for herself, her account of life in Newgate, rapidly reducing her and all its inmates to a stone-like state, “Stupid and Senseless, then Brutish and thoughtless” (278), would lead us to expect a no-better-than-average performance—if it were not for her proven ability to rise to the toughest of challenges. When “brought to my Tryal” on the Friday, she is fresh and vigorous: “I had exhausted my Spirits with Crying for two or three Days before, that I slept better the Thursday Night than I expected, and had more Courage for my Tryal, than indeed I thought possible for me to have” (284). Moll faces her moment in court as a test of personal courage, strength and above all of her ability to give “good words.” She is so eager to address the jury that the judges have to explain: “the Witnesses must be heard first, and then I should have time to be heard.”

The witnesses are, of course, the “hard-Mouth’d Jades.” Moll reports their words carefully:

tho’ the thing was Truth in the main, yet they aggravated it to the utmost extremity, and swore I had the Goods wholly in my possession, that I had hid them among my Cloaths, that I was going off with them, that I had one Foot over the Threshold when they discovered themselves, and then I put tother over, so that I was quite out of the House in the Street with the Goods before they took hold of me, and then they seiz’d me, and brought me back again, and they took the Goods upon me … (285-86)

Speaking impromptu, as she must, Moll says nothing to refute the ‘aggravating’ circumstance of the goods being “hid … among my Cloaths,” but pins much on the liminal position of her foot (or feet?) at the moment she is grabbed: “I believe, and insisted upon it, that they stop’d me before I had set my Foot clear of the Threshold of the House” (285). Her main defence, however, consists of the two negative arguments she has been offering throughout, plus an ingenious new explanation of what she had been doing in Anthony Johnson’s house:

I pleaded that I had stole nothing, they had lost nothing, the Door was open, and I went in seeing the Goods lye there, and with Design to buy, if seeing no Body in the House, I had taken any of them up in my Hand, it cou’d not be concluded that I intended to steal them, for that I never carried them farther than the Door to look on them with the better Light. (285)

This story sounds plausible enough, as Moll had never been clear about the nature of the space she had entered;[15] but “[t]he Court would not allow that by any means, and made a kind of Jest of my intending to buy the Goods, that being no Shop for the Selling of any thing.” The Judge’s joke opens the way for the maids to add their own “impudent Mocks” on the need for more light: they “spent their Wit upon it very much; told the Court I had look’d at them sufficiently, and approv’d them very well, for I had pack’d them up under my Cloathes, and was a going with them” (284-85).

No holds are barred in this battle of wits: mockery plays its part alongside straight affirmation of fact, fine distinctions and logical analysis. Less neatly and sequentially-ordered than it would be a modern trial, testimony is given, challenged and counter-challenged in a contest for the jury’s favor in which the judges act as not very impartial umpires (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 342). A true oral ‘altercation’ between contestants, Defoe’s fictional trial exemplifies Langbein’s model of common law procedure as it was before the lawyers took charge. The witnesses’ words come through clearly, with Moll resembling Langbein’s articulate challenger more closely than Beattie’s feeble defendants. Their performances realize in fiction a key moment in the ideal process of English criminal justice in the early eighteenth century.[16]

In the last phase of her trial Moll is once more called on to speak in public for herself. She has been “found Guilty of Felony, but acquitted of the Burglary” (285), the acquittal being, as Moll comments bitterly, “but small Comfort to me, the first bringing me to a Sentence of Death, and the last would have done no more” (285). By the standards of her time the verdict is a harsh one. In general Old Bailey juries acquitted around 40% of all those charged, whereas less than 19% of my sample was found not guilty. Moll’s jury has also failed to apply any of the mitigating options commonly used to avoid death sentences for non-violent crimes. It has not downgraded the capital felony charge to non-capital larceny (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 428), nor has it apparently brought the value of the goods stolen below the five shillings for which a death sentence was mandatory, as they did in the trials of a full seventeen of Moll’s real counterparts. Eschewing these outcomes, Defoe sends Moll to join the small group of the six actual shop-lifters who, out of the thirty tried and found guilty at the Old Bailey in 1720-21, were condemned to death.[17]

The fictional sentencing scene is one of high drama. This is how Moll faces her judges for the last time:

The next Day, I was carried down to receive the dreadful Sentence, and when they came to ask me what I had to say why Sentence should not pass, I stood mute a while, but some Body that stood behind me prompted me aloud to speak to the Judges, for that they cou’d represent things favourably for me: This encourag’d me to speak, and I told them I had nothing to say to stop the Sentence; but that I had much to say, to bespeak the Mercy of the Court, that I hop’d they would allow something in such a Case, for the Circumstances of it, that I had broken no Doors, had carried nothing off, that no Body had lost any thing; that the Person whose Goods they were was pleas’d to say, he desir’d Mercy might be shown, which indeed he very honestly did, that at the worst it was the first Offence, and that I had never been before any Court of Justice before: And, in a Word, I spoke with more Courage than I thought I cou’d have done, and in such a moving Tone, and tho’ with Tears, yet not so many Tears as to obstruct my Speech, that I cou’d see it mov’d others to Tears that heard me. (285-86)

Defoe manages Moll’s transition from silence to eloquence carefully. Her offence is not clergyable, and she is too old to follow her mother’s example and claim pregnancy (8), so she has indeed “nothing to say to stop the Sentence.” But as to “bespeaking mercy” she is eloquent, once prompted to speak by that mysterious “some Body” standing behind her.[18] This person is clearly well-versed in court practice: her judges could indeed “represent things favourably” by including Moll’s name in the list of those deemed to deserve ‘administrative’ pardon which, at the end of every session, they sent the secretaries of state (Beattie, Policing and Punishment 288). Rehearsing the mitigating “Circumstances,” she adds new emotional force to her appeal. Thick with verbs of asking, speaking, representing, telling, saying and hearing, particulars of tone and gesture, her report foregrounds the orality and theatricality of her speech. It is a masterly performance, one that moves some to tears, but apparently not the decision-makers:

THE Judges sat Grave and Mute, gave me an easy Hearing, and time to say all that I would, but saying neither Yes, or No to it, Pronounc’d the Sentence of Death upon me; a Sentence that was to me like Death itself, which after it was read confounded me; I had no more Spirit left in me, I had no Tongue to speak, or Eyes to look up either to God or Man. (286)

The ‘accused speaks’ trial thus concludes with the judges “pronouncing” their “Sentence,” the condemned woman unable now to use her tongue, or even make the traditional gesture imploring divine mercy. The contrast between this fictional account and the bare lists of names offered by the Proceedings is marked. At end of the four-day session held in early September 1720, for example, readers were told merely that:

The Tryals being over, the Court proceeded to give Judgment as followeth;

Receiv’d Sentence of Death, 10.

James Wilson , John Homer , Edward Wright , James Holliday, James Norris , Henry Emmery , Robert Jackson , Katharine Crompton, John Tomlimson, and Anthony Goddard. (s17200907-1)

We hear nothing here of judge’s warnings or vindications of the law, or of prisoners’ pleas for mercy, and are given no sense of solemn ritual. As with defence statements, this silence does not prove that nothing was said, though later in the century there were complaints about the “desultory” manner in which sentencing was conducted (qtd. in King 336). As to these prisoners, surely a few of the ten condemned that day would have had something to say in the hope of gaining at least a respite. Three of the six shoplifters sentenced to die were certainly reprieved, and it would have been at this stage that they could have put their cases to the bench. Two of the women (Conner and Jones) must have ‘pleaded their bellies,’ for they were respited for pregnancy, and presumably there was an exchange in which Evans agreed to undergo medical experiment and had his death sentence remitted. We do not know what happened to Mary Hughes (t17200115-3), Henry Emmery (17200907-16) or Katharine Crompton (t17200907-30), but there is no trace of them in the extant Ordinary’s Accounts for the months following their trials, so they may have got off. Of the thirty in my sample who were accused and found guilty of shoplifting none was certainly hanged, and twenty-seven were definitely not.

By far the majority of the latter, twenty-two, were sentenced directly to transportation. Moll too will escape the fatal tree and be sent to Virginia, though only in extremis. She is evidently not on the judges’ list recommending ‘administrative’ pardons, for her name is on the dead warrant sent down to Newgate twelve days after her trial (289). In the meantime, however, she has been brought to true repentance by the good minister sent by her Governess. It is he who obtains a last minute reprieve (290), giving Moll time to make “but not without great difficulty … an humble Petition for Transportation” (293).[19] Her petition is granted, though we are not told on what grounds, but her trial judges would have been consulted, and one wonders whether Moll’s eloquence in court had not contributed to some extent. Perhaps the “easy hearing” she receives from her Old Bailey judges stands metonymically for the “easy reading” we, throughout the novel, accord her many “good Words.”

6. Credible, surprising, edifying?

Where does this leave Defoe’s narrative of the prosecution of Moll Flanders? How does it compare to the story we have extrapolated from reports of trials of real thieves going through London’s central criminal court in the early 1720s? And how might we interpret Defoe’s adhesion to or divergence from the expectations readers of those reports would bring to Moll’s story?

On the whole, Defoe’s account of the prosecution of Moll Flanders would not have grossly violated early eighteenth-century assumptions about who might do what, when, where and how at the scene of a theft and subsequently. She is caught by people on the spot, prosecuted by her victim and goes through the pre-trial procedure as laid down by law. A bill of indictment against her is found true by a grand jury, and before a petty jury she directly confronts the witnesses against her according to the old ‘accused speaks’ trial format. If in the end she is convicted but avoids execution, her salvation is accomplished according to standard pardoning procedure, enabling her to join the large numbers of transported property offenders. By telling us what nearly happens to her, or happens to her associates, Defoe extends his coverage of the probable; he has Moll avoid the usual methods of fencing stolen goods, hinting at the dangers that lay that way, and he makes her live in dire fear of being tracked down by accomplices, thus pointing to ways of catching thieves that were commonly used and reported in his time.

Yet as we have seen, Moll’s story includes silences and emphases which detract from rather than reinforce credibility. Years ago J. Paul Hunter remarked that even in the midst of verisimilitude we long for the marvelous, the strange and surprising (30-34), and Wolfram Schmidgen recently argued that we should turn to Defoe less for realism than for the various and surprising (96). Hunter also insisted that we take the didactic intentions of eighteenth- century novels seriously, recognizing that they respond to the needs and desires of their readers (ch.11). When Moll’s editor insists that we “make the good Uses” of her life (2), and learn something “from every part,” he means us to read for practical instruction in crime management as well as for moral and religious guidance (4). Can either or both of these counsels help us to “know how to Read” Moll’s progress along his or her route from arrest to committal, from committal to trial, and from trial to punishment or pardon?

We have noticed, for instance, that Defoe excludes from his cast the professional thief-takers who sent many robbers and burglars to their deaths, and who did not turn up their noses at the chance of profiting from the occasional shoplifter. I suspect that he did not eschew these figures out of fear that the reader might find them dull and predictable, but because he preferred not—at least not here—to bring to his public’s attention the role played by blood money in the administration of English justice. The uncertain wording of Moll’s indictment raises the prospect of a turn in her favor and hence an element of suspense, but also warns potential prosecutors to take care in framing their charges. If the verdict against her is more severe than those usually handed out to women shoplifters, this too adds tension and suspense, but also reinforces the warning to thieves which was certainly an item on Defoe’s agenda. It is also a necessary prelude to a death-sentencing scene for which there is no equivalent in the Proceedings, one which adds dramatic interest, but also magnifies the solemnity of criminal court practice.

Perhaps most surprising of all Defoe’s emphases, however, is the clarity and force with which he amplifies the voices of plebeian women as they negotiate with constables, magistrate, and grand jurymen, and fight out their battle for the hearts and minds of the Old Bailey bench and jury. Anyone who followed the trials of petty thieves in the Proceedings would surely have been struck by the energy, intelligence and pathos with which an uneducated, elderly shop-lifter argues her own defense in every “room” along the corridor of prosecution, and especially in that theatrical Sessions House. He or she might also have been struck by the Governess’s tenacious negotiating with prosecution witnesses and grand jurymen. Perhaps even more striking would have been the ways in which two maid-servants dominate the process of prosecution, not merely grabbing Moll at the scene of the crime but fetching the constable of their own initiative, keeping the Justice of the Peace to the rule book, defying their mistress and forcing a reluctant master first to indict for burglary a woman taken in a “bare Attempt,” and then, in defiance of all claims to compassion, never mind gender solidarity, and with no prospect of material benefit, persist with the case right through to the shadow of the gallows. We know from social history—such as Lawrence Stone’s study of divorce cases Broken Lives, and Carolyn Steedman’s Labour’s Lost (30)—that early modern law allowed (and sometimes forced) many ordinary and illiterate people to speak of their experiences in a wide range of contexts. Paula Humfrey, who has studied defamation suits and settlement hearings in which domestic servants deposed has called them ‘highly visible participants of public life’ (29). Perhaps these wenches’ bellowings would have surprised Defoe’s readers less than they do us now. But it is probably still fair to say that his telling of the prosecution and trial of Moll Flanders foregrounds the active and articulate roles played by women near the bottom of society in the practical administration of justice in early eighteenth-century England.

If so, questions arise not only about Defoe’s rhetorical purposes, but also about the part he may have played in changing the way law enforcement was narrated. Did Moll Flanders—and Colonel Jack too—influence the representation of actual judicial process? In the early 1720s the Old Bailey Proceedings were still meagre publications of four to nine pages from which the actual words of witnesses were almost wholly absent; Moll Flanders is a reporter ahead of her time, anticipating the verbatim transcriptions and dramatic presentation of evidence that begin to be included from the end of the decade in which she appeared on the London scene. Did Defoe’s full, first-person account of an ordinary thief fighting for her life help bring about that development, and stimulate the growth of critical interest in testimony, its value and its reliability? My enquiry started from the hypothesis that the Proceedings journalist could have been of help to a master of fictions—but that master of fictions may also have been of help to the Old Bailey reporter, and to the long line of his successors in the narrating of true crime, its prosecution and punishment.

Ca’ Foscari University of Venice

NOTES

[1] I am most grateful to Robert Shoemaker and Shelley Tickell for reading so carefully an earlier version of this essay, and to the Digital Defoe referees for precise and useful suggestions. I would also like to thank Danièle Berton and the research group who organized the colloquium “Témoigner: De la Renaissance aux Lumières” at the Université Blaise Pascal in November 2011; this essay grew out of a paper presented on that occasion and a French version of it is forthcoming in the proceedings (Editions Honoré Champion Paris). In its turn the essay will be the nucleus of a book-length study dealing also with Colonel Jack and non-fiction, provisionally entitled Catching Thieves: Defoe and Law Enforcement in Eighteenth-Century England. Paola Pugliatti and Giacomo Mannironi continue to give their invaluable advice and encouragement to this project.

Shoplifting because this is one of Moll’s two specialities. All data on trials are taken from Hitchcock et al., The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674–1913. My sample of trials consists of those produced by a search on “offense = shoplifting” and limited by date to 1720–1721—with one exception: I have eliminated t17210113-9, in which Thomas Knight was found guilty of stealing £6666 5s worth of jewellery from the shop of the well-known ‘toyman,’ William Deard (Battestin 55), because Knight used an auger to get into the shop and was surely on trial for burglary. As we shall see, Moll too will be accused of burglary, but she clearly thought she was “stealing privately,” i.e. without breaking in and without being seen. I am grateful to Shelley Tickell for drawing my attention to the crime categorization problems arising from the Proceedings’ failure to state under which statutes prosecutions were brought.

[2] For a comparison between the Account and the Proceedings, see Faller, Turn’d to Account, and Clegg, “Moll Flanders, Ordinary’s Accounts and the Old Bailey Proceedings,” 108–109. Andrea Mckenzie shows that violent crimes were hugely over-represented in the select trials; on the volume most pertinent to Moll Flanders, the 1718-21 Compleat Collection of the Most Remarkable Tryals, see 52–54.

[3] Tickell suggests that some of the new features of shops were in fact designed to prevent shop-lifting (304).

[4] In chronological order of appearance in court: Elizabeth Simpson (t17200115-3); Thomas Johnson (t17200115-29); John Tracey (t17200907-02); Margaret Elson (t17201207-9); Ann Wood (t17210113-23); William Moor (t17210525-53); Edward Thomas (t17211206-38); John Nash (t17211206-73).

[5] Thomas Kingham (t17200303-12); Zephaniah Martin (t17200427-56); Thomas Riggol (t1721071206-73); Ann Nicholls (t17211206-2); John Alcock (t17211206-27).

[6] Thanks again to Shelley Tickell for pointing out that, since Crompton was seen taking the muslin, she may not have been charged under the 1699 Shoplifting Act, which covered stealing privately, but (since shops were so often parts of houses), under the 1713 law which made stealing goods of over 40 shillings from a house a capital offence, and this could explain her death sentence. The same might apply to Mary Hughes (who was also condemned to death); yet Susannah Lloyd, Margaret Townley and Thomas Rice too were seen taking the goods and were sentenced instead to transportation. It is evident, in any case, that all of them meant to take the goods by stealth so I have treated all five as shoplifting trials.

[7] All the more strange if, as I am convinced, the True and Genuine Account of the Life and Actions of the Late Jonathan Wild (1725) is by Defoe (Clegg, “Inventing Organised Crime”).

[8] For detailed comment on these scenes see Faller, Crime and Defoe 152–53; Clegg, “Popular Law Enforcement,” 530–31.

[9] Thus Richard Evans and Elizabeth Pool (t17200115-34); Susannah Lloyd (t17200303-38); Henry Emmery (t17200907-16); Hannah Conner (t17201207-6); James Codner (t17201207-12); Ann Nicholls (t17211206-2); Robert Lockey (t17210830-3); Edward Thomas (t17211206-38).

[10] The fourth was enlistment in the armed forces.

[11] I am grateful to one of my referees for bringing my attention to chapbook abridgements in which the title pages assert that Moll was “15 Times whipt at the Cart’s Arse”; this was a standard punishment for disorderly women, but Shoemaker has found magistrates committing thieves to houses of correction as well (Prosecution and Punishment 172).

[12] Simpson (t17200115-3); Evans and Pool (t17200115-34); North (t17200303-10); Crompton (t17200907-30); Conner (t17201207-6); Codner (t17201207-12); Pritchard (t17210830-25); Rice (t17211011-5).

[13] If one were to take seriously the claim that Moll’s story was “[w]ritten in the Year 1693,” she would be ahead of history in assuming a clear-cut distinction between capital and non-capital offences; throughout the seventeenth century anyone (even a woman, after 1623), could claim benefit of clergy for many crimes (Beattie, Crime and the Courts 142-43).

[14] Unlike her attempts to tamper with the witnesses, these “endeavourings” do not take the form of bribes, but the phrase may have rung alarm bells with Defoe’s early readers. As G.A. Starr notes (390n), jury corruption was highly topical. In 1721 a bill had been introduced for preventing it, and in March 1722 Defoe was writing optimistically of a “Law lately pass’d” to that effect; Starr finds no such new law reaching the statute book at this time however.

[15] In her first telling of the theft Moll states that “it was not a Mercer’s Shop, nor a Warehouse of a Mercer, but look’d like a private Dwelling-House” (272). Because shops occupying parts of dwelling-places would have been familiar to Defoe’s early readers, her uncertainty is less ridiculous than the judge’s sneer implies.

[16] I am grateful to Robert Shoemaker for reminding me that, because of the scant attention paid by Old Bailey reporters to the defense, Defoe’s account may have been more true to what actually took place in court than the Proceedings.

[17] Mary Jones (t17200115-3); Evans (t17200115-34); Hughes (t17200115-40); Emmery (t17200907-16); Crompton (t17200907-30); Conner (t17201207-6).

[18] Whoever this person is, in trying to help Moll he (or possibly she) is typical of eighteenth-century trial audiences, which in property cases “tended overwhelmingly to favour mercy” (King 256). On the other hand, he may have been one of those ‘Newgate attorneys’ who frequented the courts and prisons in order to pick up clients and keep abreast of current trends (Beattie, Policing and Punishment 396-99).

[19] In Policing and Punishment, Beattie (288-89) distinguishes between special pardons for named individuals, expensive documents inscribed on parchment, and “general” or “circuit” pardons for groups of “poor convicts” held in a particular gaol or gaol of an assize circuit. It would have been onto one of the latter type that Moll’s younger colleague had earlier got her name after “starving a long while in Prison” (Defoe 204 and Starr n3). It often took a long time for such documents to pass under the Privy Seal, so if Moll’s pardon too is of this type, she is lucky in having to wait only two weeks, and in having managed to conceal the wealth she will take to Virginia: those “able to bear the charge of a particular pardon” were supposed to be excluded from circuit pardons. There would indeed have been “great difficulty” in drawing up the petition; of the arguments most frequently successful–old age, youth, infirmity, distressed circumstances, and proof of having “lived in a neighbourly, honest, and orderly manner” (King ch 9)–only the first is available to Moll. The one most likely to have been used by the minister, “signs of reformability” was, according to King, not often successful and was rarely employed (289).

WORKS CITED

Battestin, Martin C. A Henry Fielding Companion. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000. Print.

Beattie, J. M. Crime and the Courts in England, 1660-1800. Oxford UP, 1986. Print.

———. Policing and Punishment in London 1660-1750 : Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Chaber, Lois A. “Matriarchal Mirror: Women and Capital in Moll Flanders.” PMLA 97.2 (1982): 212–26. Print.

Clegg, Jeanne. “Inventing Organised Crime: Daniel Defoe’s Jonathan Wild.” Many Voicéd Fountains: Studi di Anglistica e Comparatistica in Onore di Elsa Linguanti. Ed. Mario Curreli and Fausto Ciompi. Pisa: ETS, 2003. Print.

———. “Moll Flanders, Ordinary’s Accounts and Old Bailey Proceedings.” Liminal Discourses, Subliminal Tensions in Law and Literature. Ed. Daniela Carpi and Jeanne Gaakeer. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013. 95–112. Print.

———. “Popular Law Enforcement in Moll Flanders.” Textus 21 (2008): 523–46. Print.

[Defoe, Daniel]. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, Who Was Born in Newgate, and during a Life of Continued Variety for Sixty Years Was 12 Times a Whore, 5 Times a Wife, Whereof Once to Her Own Brother, 12 Times a Thief, 11 Times in Bridewell, 9 Times in the New Prison, 11 Times in Wood-Street Compter, 6 Times in the Poultry Compter, 14 Times in the Gate-House, 25 Times in Newgate, 15 Times Whipt at the Cart’s Arse, 4 Times Burnt in the Hand, Once Condemned for Life, and 8 Years a Transport in Virginia. At Last Grew Rich, Lived Honest, and Died Penitent. [London]: N.p., 1760. Gale. Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

———. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, Who Was Born in Newgate, And during a Life of Continued Variety for Sixty Years, Was 17 Times a Whore, 5 Times a Wife, Once to Her Own Brother, 12 Years a Thief, 11 Times in Bridewell, 9 Times in New Prison, 11 Times in Wood-Street Compter, 6 Times in the Poultry Compter, 14 Times in the Gate-House, 25 Times in Newgate, 15 Times Whipt at the Cart’s Arse, 4 Times Burnt in the Hand, Once Condemned for Life, and … Years a Transport in Virginia. At Last … Rich, Lived Honest and Died a Penitent. [London]: N.p., 1750. Gale. Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

———. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, Who Was Born in Newgate. And during a Life of Continued Variety for Sixty Years Was 17 Times a Whore, 5 Times a Wife, Whereof Once to Her Own Brother, 12 Years a Thief, 11 Times in Bridewell, 9 Times in New-Prison, 11 Times in Wood-Street Compter, 6 Times in the Poultry Compter, 14 Times in the Gatehouse, 25 Times in Newgate, 15 Times Whip That the Cart’s Arse, 4 Times Burnt in the Hand, Once Condemned for Life and 8 Year’s a Transport in Virginia. At Last Grew Rich, Lived Honest, and Died Penitent[.]. [London]: N.p., 1750. Gale. Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

Defoe, Daniel. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, &c. Ed. G.A. Starr. London: Oxford UP, 1971. Print.

Faller, Lincoln B. Crime and Defoe : A New Kind of Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993. Print.

———. Turned to Account : The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1987. Print.

Gladfelder, Hal. Criminality and Narrative in Eighteenth-Century England: Beyond the Law. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 2001. Print.

Hitchcock, Tim, Robert Shoemaker, Clive Emsley, Sharon Howard and Jamie McLaughlin, et al., The Old Bailey Proceedings Online, 1674-1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.0, 24 March 2012). Web. 13 Nov. 2014.

Humfrey, Paula, ed. The Experience of Domestic Service for Women in Early Modern London. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011. Print.

Hunter, J. Paul. Before Novels: The Cultural Contexts of Eighteenth-Century English Fiction. New York: Norton, 1990. Print.

King, Peter. Crime, Justice, and Discretion in England, 1740-1820. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000. Print.

Koonce, Howard L. “Moll’s Muddle: Defoe’s Use of Irony in Moll Flanders.” ELH 30.4 (1963): 377–94. Print.

McKenzie, Andrea. “‘Useful and Entertaining to the Generality of Readers’: Selecting the Select Trials, 1718-1764.” Crime, Courtrooms and the Public Shere in Britain, 1700-1850. Ed. David Lemmings. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012. 43–70. Print.

Mui, Hoh-Cheung, and Lorna H. Mui. Shops and Shopkeeping in Eighteenth-Century England. Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s UP, 1989. Print.

Schmidgen, Wolfram. “Undividing the Subject of Literary History: From James Thomson’s Poetry to Daniel Defoe’s Novels.” Eighteenth-Century Poetry and the Rise of the Novel Reconsidered. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell UP, 2014. 87–104. Print.

Shoemaker, Robert. The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England. London: Hambleton and London, 2004. Print.

———. “The Old Bailey Proceedings and the Representation of Crime and Criminal Justice in Eighteenth-Century London.” The Journal of British Studies 47.03 (2008): 559–80. Print.

———. “Print and the Female Voice: Representations of Women’s Crime in London, 1690–1735.” Gender & History 22.1 (2010): 75–91. Print.

———. Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex, c.1660-1725. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991. Print.

Starr, G. A. Introduction and Explanatory Notes. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of The Famous Moll Flanders, &c. London: Oxford UP, 1971. vii–xxix, 345–98. Print.

Steedman, Carolyn. Labours Lost: Domestic Service and the Making of Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. Print.

Stone, Lawrence. Broken Lives: Separation and Divorce in England, 1660-1857. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993. Print.

Swaminathan, Srividhya. “Defoe’s Alternative Conduct Manual: Survival Strategies And Female Networks in Moll Flanders.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 15.2 (2003): 185–206. Print.

Swan, Beth. Fictions of Law: An Investigation of the Law in Eighteenth-Century English Fiction. New York: P. Lang, 1997. Print.

Tickell, Shelley. “The Prevention of Shoplifting in Eighteenth-Century London.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 2.3 (2010): 300–13. Print.