I.

WASHED ASHORE after a shipwreck, Robinson Crusoe walks distractedly about, wordlessly giving thanks to God for his reprieve, making “a Thousand Gestures and Motions which I cannot describe,” and grievously lamenting the loss of his comrades (RC 41, n.284). Recalling the moment sixty years later as he writes his memoirs, Crusoe still finds it “impossible to express to the Life what the Extasies and Transports of the Soul are” when a man is saved out of the very grave. He resorts to quoting a line of verse to convey the confusion of joy and grief that he felt upon finding himself safe on shore: “For sudden Joys, like Griefs, confound at first.”i The line is a talisman for a theme that runs throughout The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe—the power of joy, and its twin passion, grief, to render affected humanity speechless, ecstatic, even senseless. Crusoe experiences the overwhelming power of sudden joy not once, but sixteen times in the course of the first volume of his travels, and he is surprised by grief another twelve times.ii

Crusoe is aware that these moments have profound philosophical and spiritual significance, though he is unable to say what it is. Had he been a scholar, as Daniel Defoe was, he might have known that joy and grief (or sorrow) are the nearly indistinguishable passions in which, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, all other passions, and most narratives, terminate (Potkay 13-14). They differ only in their objects: joy tends towards the good, or union with God; grief tends towards evil, or separation from God. Of all the passions, they are the most likely to apprehend men and women suddenly, by surprise (Miller 63-4).

Of Robinson’s experiences of “sudden Joy,” the most surprising come in the course of his encounters with an unnamed figure whom he calls by such euphemisms as “my good old Captain,” “my old Patron, the Captain,” and “my old Portugal Captain” (RC 238, 240). Crusoe is profoundly affected three times by his encounters with this Portuguese captain, who treats him like a brother despite the national prejudices that separate them and the adverse historical circumstances in which they meet. It is the Portuguese captain who saves Crusoe from being lost at sea in a small boat, who carries him in freedom to Brazil and sets him up as a planter, and who, at the end of the first volume of his travels, restores his lost wealth. The extraordinary charity of the Portuguese captain, who is unrelated to Crusoe and seeks no return on his goodness, has not been fully explored by any of the commentators who have noticed him.iii Most commentators see the captain’s kindness merely as an example of selfless humanity that does not require further examination, even though his goodness is an anomaly in Crusoe’s fictional world, which is populated largely by criminals, pirates, cannibals, mutineers, and renegades. The captain’s inexplicable goodness and his central role in the story are sufficient reasons to consider more closely his place in the history of Crusoe’s life.

II.

Crusoe’s first encounter with the Portuguese captain occurs soon after his escape from the North African port of Salé, after having been held in captivity for two years by a Turkish rover. A timeline of the significant dates in Crusoe’s life suggests that the year of his escape was 1654.iv In that year, Oliver Cromwell dictated to King John IV the terms of a treaty of peace between England and Portugal, which ended an “undeclared war” that had begun around 1650.v The treaty gave English merchants the right to trade with Portuguese colonies in Brazil, so long as the goods passed through Lisbon in transit. In the next year, 1655, an English fleet under Admiral Robert Blake forced the Bey of Algiers to repatriate the English slaves in his dominion, which would have included Crusoe (Napier 424).vi Defoe may have chosen 1654 because, prior to that year, England and Portugal were still at war, and an Englishman would have been unwelcome on board a Portuguese ship; after 1655, it is unlikely that Crusoe would have been held as a slave by the Algerian pirates, thus precluding his escape, his subsequent adventures in Brazil, and his confinement on a Caribbean island. The year 1654 was therefore the most probable time in which Defoe could frame Crusoe’s friendly encounter with the Portuguese captain.

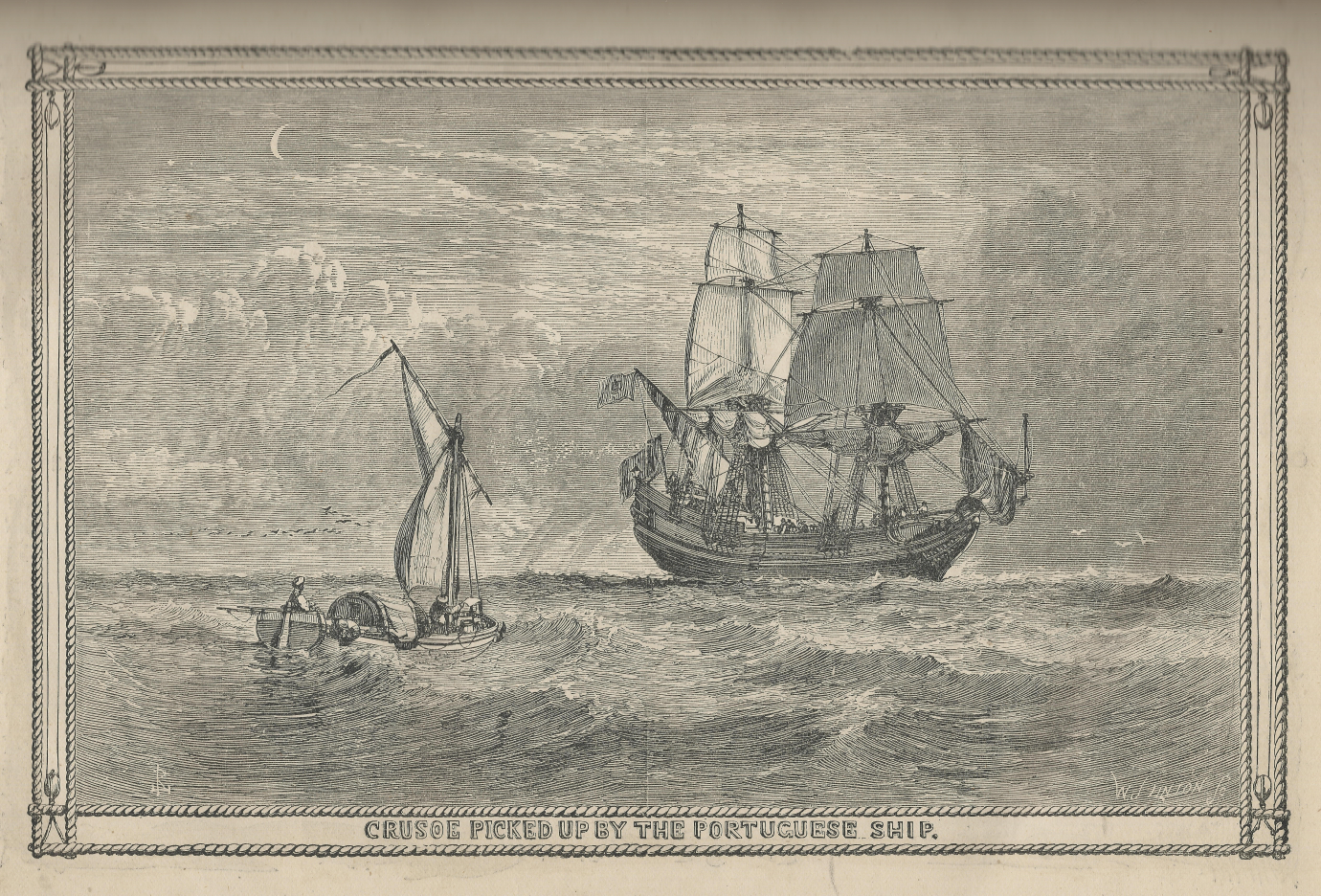

Fig. 1. “Crusoe picked up by the Portuguese Ship.” Engraved by W. J. Linton. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1863.

After escaping from his Algerian “Patron or Master” (18), Crusoe sails south in a small boat with Xury down the coast of Africa. After a voyage of about a month, Crusoe rounds Cape Verde and sees the Atlantic Ocean before him, with the Cape Verde Islands about 300 miles to windward. Uncertain about the safety of the mainland on his left and unsure if he can reach the Islands on his right, Crusoe faces the prospect of sailing on into the South Atlantic, with no landfall until he reaches Brazil, 2500 nautical miles distant. In this unhappy predicament, Xury cries to him, “Master, Master, a Ship with a Sail” (29). All ships at sea at this time had sails, so presumably the ship that Xury sees is a carrack, a square-rigged vessel capable of crossing the Atlantic, rather than a caravel, a coasting vessel with a lateen, or triangular sail (Boxer, Portuguese Seaborne Empire 27-8, 207).vii Crusoe deduces correctly that a carrack sailing westerly from the coast of Guinea must be a Portuguese ship carrying slaves. Crusoe is himself an escaped slave, though a European, so he knows that there is nothing to prevent the captain of the Portuguese ship from taking him prisoner, as well as Xury, and selling them both when they arrive in Brazil, particularly because Crusoe must assume that England and Portugal are still at war. In this “miserable and almost hopeless Condition” (30), Crusoe faces either a slow death at sea or life in servitude. His despair suddenly converts to “inexpressible Joy” when the ship’s captain, having discovered that he is an Englishman, “bad me come on board, and very kindly took me in, and all my Goods” (29). In gratitude for being delivered from his desperate circumstances, Crusoe offers “all I had to the Captain of the ship” (30). The Portuguese captain graciously declines Crusoe’s offer with a speech that is an example of Christian charity, such as one would expect to find in a sermon rather than on a slave ship at sea. The captain promises to treat this English stranger as he would hope to be treated himself in similar circumstances: he assures Crusoe that “I have sav’d your Life on no other Terms than I would be glad to be saved my self, and it may one time or other be my Lot to be taken up in the same Condition” (30). The captain’s speech is a plain-spoken paraphrase of the Golden Rule taught by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount: “So whatever you wish that men would do to you, do so to them; for this is the law and the prophets” (Matthew 7:12).

In the Gospel according to Luke, the same ethical principle is presented dramatically. A lawyer challenges Jesus to explain the way to inherit eternal life. Jesus asks the lawyer what is written in the law, and he replies by quoting two commandments of Moses: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your Heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind; and your neighbor as yourself” (Luke 10:25-8).viii When the lawyer asks whom he should consider his neighbor, Jesus tells him the parable of the good Samaritan: A man on his way from Jerusalem to Jericho was attacked by thieves, who wounded him and left him for dead. His body was passed by a priest and a Levite, neither of whom assisted him. A Samaritan, however, felt compassion for him, poured oil and wine on his wounds, conveyed him to an inn at Jericho, and provided for his care during his recovery. Jesus asks the lawyer which of the three has fulfilled Moses’s second command, and the lawyer answers, “He that showed mercy on him,” to which Jesus replies, “Go, and do thou likewise” (Luke 10:29-37).

Defoe’s re-telling in Robinson Crusoe of the Samaritan parable makes use of several salient features of the original. The Portuguese were considered an inferior, mixed-race people by many Europeans, much as the Samaritans were regarded as inferior by the Jews, so the charity of the Portuguese captain is as extraordinary as the Samaritan’s mercy toward his “neighbor,” the traveler. The captain buys Crusoe’s boat and goods at a very generous price, as well as Crusoe’s boy Xury, though he might easily have confiscated these goods without payment. He promises to free Xury after ten years, thus granting Crusoe cover for his unchristian act of selling the boy’s liberty. The Portuguese captain pours oil and wine, albeit in the form of his kind words and deeds, on Crusoe’s fears and grief and carries him to Brazil (or, in the parable, the inn at Jericho), where his cure begins. He frees Crusoe of any debt for the passage and sets him up on a sugar plantation. He helps Crusoe obtain “a kind of a Letter of Naturalization,” which (many years later) Crusoe admits required him to profess himself a Roman Catholic (241).

Crusoe and his neighbor, an Anglo-Portuguese named Wells, are able to grow enough food in Brazil to subsist on, but very little more (31). By the intervention of his old friend the captain, who has not yet returned to Portugal, Crusoe is advised to write “Letters of Procuration” that will allow his banker in London to send money and goods to Lisbon, which the captain will re-export to him in Brazil. This seemingly complicated financial arrangement is, in fact, necessary for historical reasons: due to the provisions of the Anglo-Portuguese trade agreement of 1654, no English ships could travel directly from the British Isles to Brazil; all trade had to pass through Lisbon, where it was licensed for export and additional duties were paid (Boxer, “English Shipping” 213). The captain returns to Lisbon, where he receives a cargo of “all Sorts of Tools, Ironwork, and Utensils necessary for [Crusoe’s] Plantation” (33) and brings them in his own ship to Brazil. When the cargo arrives, Crusoe is “surprised with the Joy of it,” particularly because the captain has also bought for Crusoe, with his own commission of £5, a “Servant under Bond for six Years Service,” perhaps a replacement for Xury, whose sale Crusoe now regrets. Like the Samaritan who provides for the wounded man’s care at Jericho, and also promises further assistance when he returns, the captain plays an essential role in facilitating Crusoe’s transformation from slavery to a subsistence farmer to a capitalist planter. The captain’s service to Crusoe is an extraordinary act of charity, particularly surprising because it is performed by a person of a mixed, and thus supposedly inferior, race. Nothing would have prevented the captain from absconding with Crusoe’s goods and money in Lisbon, except his resolve to treat his neighbor as he would be treated himself. Crusoe’s joy proceeds from his discovery that such goodness may be found in the world, even in a Portuguese.

Unfortunately, the benevolent captain’s return to Lisbon prevents him from extending any further guidance to Crusoe, who is tempted by a “secret Proposal” from a company of merchants and planters in Brazil to undertake a slaving voyage to the coast of Guinea. As Crusoe knows, such a voyage was forbidden except to contractors who held an asiento from the Spanish government (Boxer, Portuguese Seaborne Empire 330).ix Prior to 1640, contracts to transport slaves to Brazil were granted to the Portuguese, but after the revolution in that year, there was no asiento until 1662, when Genoese merchants were granted contracts to convey slaves in ships from the (Dutch) West Indies Company and the (English) Royal African Company. All other traders were interlopers, subject to severe punishments. Presumably, if Crusoe had the guidance of “my kind Friend the Captain” (32), his head would not have been so “full of Projects and Undertakings beyond my Reach,” which were to “cast [him] down again into the deepest Gulph of human Misery that ever Man fell into” (34). Crusoe blames his subsequent misfortunes on his neglect of his father’s advice to live “a quiet retired Life,” but in fact, he had long since rejected that advice and had prospered without it. His misfortunes, including shipwreck in an ill-advised slaving voyage, are more likely due to the absence of the Samaritan-like counselor, the Portuguese captain, whose advice and assistance had twice brought him joy.

After his deliverance from a twenty-eight-year confinement on the island, Crusoe arrives back in England on the 11th of June 1687, a date that was celebrated by many Protestants as the anniversary of the Duke of Monmouth’s ill-fated invasion of England in 1685 (Novak 82-6). (It is also very likely the time that Crusoe may be supposed to have read the poem by Robert Wild, a satirical welcome to the Declaration of Indulgence of 1672 that was indirectly related to Monmouth’s Rebellion). Crusoe’s family, other than two sisters and two nephews, is “extinct,” meaning that his inheritance is gone, and his former benefactor, the widow who had invested his money for him, is now “very low in the World,” having lost both his money and her own as well (234). Defoe seems to use the coincidence of dates to suggest a comparison between Crusoe and Monmouth: both men went into exile, both suffered trauma upon their return, and both knew grief as a result of their reverses. There is, however, one major difference: Crusoe is to be saved again by his Samaritan, who binds up his wounds and makes him whole, while the Duke found no friends among the priests and courtiers.

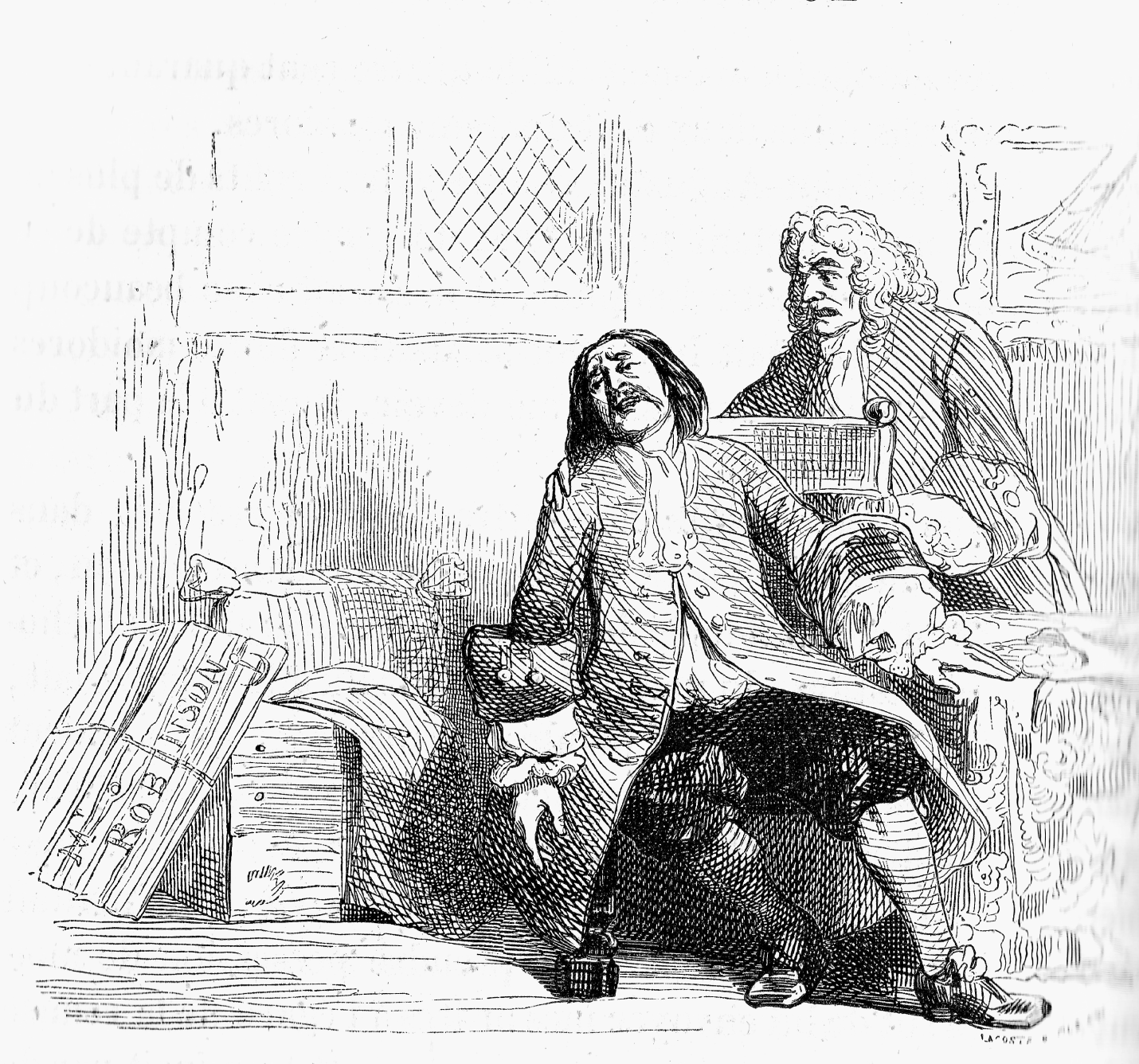

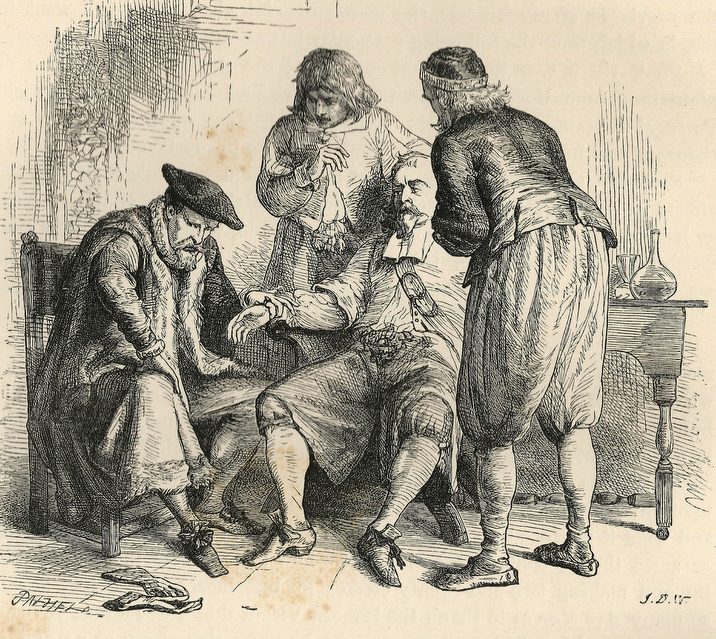

At his lowest ebb since arriving on that other island, Crusoe resolves on a voyage to Lisbon in order to seek out news of his estate in Brazil. In Lisbon, he quickly locates the Portuguese captain who, more than thirty-five years earlier, had rescued him at sea. The captain remembers Crusoe and is as improbably good to him as he had been on their first meeting. He knows Crusoe’s old partner in Brazil and the stewards, both secular and religious, who hold Crusoe’s estate in trust; his own son is managing the plantation and has paid his father the first fruits of income in trust for Crusoe, which the old man has unfortunately lost. However, the old man is ready to give Crusoe all of his money on hand, plus a half interest in his ship. Defoe uses an unmistakable marker of what would later be called the sentimental novel to express the confusion of grief and joy that overtakes his hero: “I could hardly refrain Weeping at what he said to me,” Crusoe sniffs (237). When he wonders at the captain’s generosity, the captain admits that, while “it might straiten him a little,” the money is Crusoe’s, and “I might want it more than he” (237), another proof of the unworldly selflessness that the captain showed in their first encounter. The old man’s affection for him so touches Crusoe that, once again, “I could hardly refrain from Tears while he spoke” (237-8). When all of the accounts are cast up and all of Crusoe’s ships have come in, “I turned pale, and grew sick; and had not the old Man run and fetch’d me a Cordial, I believe the sudden Surprize of Joy had overset Nature, and I had dy’d upon the Spot” (239). This grave consequence of sudden joy is averted when a physician is called, who, by letting Crusoe’s blood, is able to give vent to his animal spirits and prevent his death. The confusion of joy and grief that deprives Crusoe of speech and threatens his life is forcefully expressed in the illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by J. J. Grandville (1840) and J. D. Watson (1864) (Figures 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. “Robinson Crusoe surprised by joy.” J. J. Grandville and others, Aventures de Robinson Crusoé. Paris: H. Fournier ainé, 1840.

Fig. 3. “Crusoe needs a Physician.” J. D. Watson. London: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge, 1864.

Having accumulated and consolidated his capital, which had grown to an estate of some £5000 and an income of £1000 per year (240), Crusoe addresses the problem of what to do with his surplus wealth. In the absence of an international banking system, he must transport it back to England himself. A sea route would expose him to Algerine pirates or to shipwreck, both of which he fears from personal experience (242). Once again he turns to the Portuguese captain, whom he identifies first as “the old Man” (235), but who becomes “this ancient Friend” (237), “my good old Captain” (240), “My old Patron, the Captain” (240), and “my old Pilot” (243)—all euphemisms that stress the captain’s age, wisdom, and goodness. The old captain advises him to travel by land through Spain and France, crossing the Channel at Calais, thus greatly reducing his exposure to shipwreck or capture by pirates. The captain further assists him in forming a party of three English and two Portuguese merchants, who with two servants and Friday form a “little Troop” (243) under Crusoe’s leadership. This “little Troop,” which is transnational, multiracial, and unstratified by class, represents humanity in the allegorical reading of the Samaritan parable, which was codified by the patristic fathers of the Roman Church, among them Irenaeus, Origen, Ambrose, and Augustine. Origen was the first to identify the injured traveler in the parable as Adam, the “original” of humanity, who after the Fall is ministered to by Jesus, represented allegorically by the Samaritan (Roukema 63). Crusoe confirms this allegorical reading of the parable when he accepts the honor of leading the troop “as well because I was the oldest Man, as because I had two Servants, and indeed was the Original of the whole Journey” (243). If the Portuguese captain is analogous to the Samaritan, and the Samaritan is an allegorical representation of Jesus, then the captain is a latter-day personification of Jesus, and the joy that his acts of charity provoke in the Adamic Crusoe (who seems unaware of the allegory that explains his joy) may be more easily understood.x

Even if it is granted that the captain’s goodness mimics that of the Samaritan and that the captain is thus an allegorical emblem of Jesus, it is still unclear why this captain should be Portuguese. The association of goodness with a Portuguese is extraordinary in that it radically contradicts the character of the Portuguese sailors, soldiers, and explorers that was generally held among the English, and perhaps even by Defoe.xi The fullest expression in Defoe’s works of the English national prejudice against the Portuguese is The Life, Adventures, and Pyracies of the Famous Captain Singleton, published in June 1720, ten months after the Farther Adventures and two months before the Serious Reflections of Robinson Crusoe. Bob Singleton receives his early education at the hands of the Portuguese, from whom, he says, “I learnt particularly to be an errant Thief and a bad Sailor” (Singleton 22). As the cabin-boy for the “old Pilot” of a Portuguese carrack, not unlike the slave ship in the first volume of Robinson Crusoe, Singleton learns “every thing that is wicked among the Portuguese, a Nation the most perfidious and the most debauch’d, the most insolent and cruel, of any that pretend to call themselves Christians, in the World” (23). Thus begins a long stream of invective against the Portuguese, whom Singleton describes as “the most compleat Cowards that I ever met with”; a people capable of “Thieving, Lying, Swearing, Forswearing, joined to the most abominable Lewdness”; a nation “so brutishly wicked . . . so meanly submissive when subjected; so insolent, or barbarous and tyrannical when superiour, that I thought there was something in them that shock’d my very Nature” (23). Putting these xenophobic and racist views in Singleton’s mouth, rather than his own, allows Defoe to both express them and, ultimately, disown them as Singleton’s hatred of the Portuguese is, like Crusoe’s wanderlust or Colonel Jack’s thieving, revealed as a perversity of youth from which he is to be cured through the charity of the Samaritan-like character, William.

Another instance of anti-Portuguese prejudice is found in the Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Early in the story, Crusoe returns to his Caribbean island and speaks with one of his colonists, a “grave and very sensible Man,” who tells him that “it was not the Part of wise Men to give up themselves to their Misery, but always to take Hold of the Helps which Reason offer’d” (Farther Adventures 76). The man, who is a Spaniard, quotes a Spanish proverb, which Crusoe translates as “In Trouble to be troubl’d, / Is to have your Trouble doubl’d.” The man explicates his proverb by saying that

Grief was the most senseless insignificant Passion in the World; for that it regarded only Things past, which were generally impossible to be recall’d, or to be remedy’d, but had no View to Things to come, and had no Share in any Thing that look’d like Deliverance, but rather added to the Affliction, than propos’d a Remedy. (76)

He praises Englishmen for their “Presence of Mind in Distress,” while he laments that his own

unhappy Nation [Spain], and the Portuguese, were the worst Men in the World to struggle with Misfortunes; for that their first Step in Dangers, after the common Efforts are over, was always to despair, lie down under it, and die, without rousing their Thoughts up to proper Remedies for Escape. (76)

This disparaging stroke at the Portuguese, which resembles Singleton’s remark about Portuguese cowardice, appears at first to be gratuitous, but it serves Defoe’s narrative purpose by licensing English explorers to challenge the claims of Spain and Portugal to the exclusive right to settle colonies in the Americas on the grounds that these Iberian nations have, through their grief and neglect, turned away from God and forfeited their right to the land.xii

In his non-fiction writings as well, Defoe exploits the national prejudice against the Portuguese in order to advance his political and colonialist goals. In the Review of June 1704, “Mr. Review” mocks the Portuguese army, which he says is led by a “Wooden General” (the statue of St. Anthony of Padua, a miracle worker, which was carried before the troops). This “Hobgoblin Officer,” he scoffs, leads his troops in a “Wooden C[au]se,” and he laughs, “here is an Army of Portuguese; an Army of Portuguese, An Army of Old Alms Women! we should say….” (Defoe, Review 203-4).xiii Mr. Review’s sarcasm supports Defoe’s political argument that the “Portuguese war” must be fought with Anglo-Dutch troops, because the Spanish and Portuguese armies will make a “comedy” of it. At the other end of his writing career, in his Plan of the English Commerce (1728), Defoe encourages England to adopt Portugal’s colonial policy, even though Portugal itself is “an effeminate, haughty, and as it were, a decay’d Nation in Trade.” (Plan 121). Defoe claims that Portuguese colonies in Brazil and Africa currently import “above five Times as many [European manufactures] as were sent to the same Places, about 30 to 40 Years ago” (120), because the Portuguese cultivate their colonies as markets for their goods, rather than regarding the native populations as savage peoples to subjugate. The Portuguese, says Defoe, succeed by “bringing the naked Savages to Clothe, and instructing barbarous Nations how to live” according to “the Christian Œconomy, and . . . the Government of Commerce” (121). Defoe’s slighting allusion to Portugal as “effeminate, haughty, and . . . decay’d” is meant to suggest that Portugal’s monopoly on the trade in slaves, sugar, and coffee from Africa and Brazil, re-exported via Lisbon to English and European markets, could easily be usurped, either by separate traders (such as young Robinson Crusoe) or by the Royal African and South Sea companies. If England were to intervene in this trade and adopt a Samaritan-like policy of treating their neighbors (i.e. colonial populations) as they would be treated in their place, then the expanding English colonies in the Americas would be more civil, more religious, and more prosperous trading partners than they now are.

III.

In closing, we return to the sudden surge of joy that Crusoe experiences at pivotal moments in his life, particularly in the presence of the Portuguese captain. As we have seen, Crusoe is “surprized with Joy” at the goodness of the captain, which seems to rival that of Providence itself. The captain’s benevolence is inexplicable until we recognize the pattern in which it occurs. Crusoe suffers grief or sorrow, such as the prospect of dying at sea in his small boat, or starving as a subsistence farmer in Brazil, or ending his life in poverty after losing his fortune, but his grief is suddenly reversed into joy through the captain’s intervention. The captain is only an ordinary sailor, but in his acts of kindness he performs the part of the Samaritan in the biblical parable, binding the wounds of the fallen traveler. The patristic fathers of the Church interpret the parable allegorically, such that the Samaritan represents Jesus and the fallen traveler Adam, the “original” of humanity whose sins are redeemed by Jesus. The instrumental role of the Portuguese captain in the story is all the more perplexing in that the Portuguese, like the Samaritans in the Bible, were the least powerful, the most despised, and the least likely of all the European nations at the time to offer salvation to wounded humanity. But the very paradox of discovering charity on board a Portuguese ship moves Crusoe closer to understanding God’s providence toward post-Edenic humanity and what mankind must do to retain it. A principal duty of humanity, as Adam Potkay suggests, is to transform the extravagant joys of survival into the spiritual joys of obedience to God’s plan for the world and to become an agent in that plan (93-4).

A dramatic illustration of the effects of joy and grief on humanity is found in The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, in which Crusoe, moved by the memory of his rescue by the Portuguese captain, rescues, in his turn, the crew and passengers of a French ship that has caught fire at sea (Farther Adventures 14-19). Their “inexpressible Joy” at being rescued allows Crusoe to describe at length the “strange Extravagancies” of joy they display, which resemble the “greatest Agonies of Sorrow” (16-17). Of the sixty-four who were saved, some were

stark-raving and down-right lunatic, some ran about the Ship stamping with their Feet, others wringing their Hands; some were dancing, some singing, some laughing, more crying; many quite dumb, not able to speak a Word; others sick and vomiting, several swooning, and ready to faint; and a few were Crossing themselves, and giving God Thanks. (17)

Crusoe turns his narrative account into a taxonomic case study: many sailors and passengers give vent to their joy in a manner indistinguishable from grief; some are speechless, or ecstatic; only a few retain command of their passions and give thanks to God. On the next day, the ship’s captain and one of the priests offer to Crusoe all of the money and possessions saved from the ship in return for rescuing them, which Crusoe refuses. His refusal mirrors and repays the Portuguese captain’s generosity upon saving Crusoe many years ago. Crusoe explains that “if the Portugal Captain that took me up at Sea had serv’d me so, and took all I had for my Deliverance, I must have starv’d, or have been as much a Slave at the Brasils as I had been in Barbary” (19). In his refusal, Crusoe assumes the mantle of his mentor, the Portuguese captain, and like him, pours oil and wine on the wounds of fallen humanity. Whether he fully understands and accepts the allegory of the Samaritan parable that underlies his act is unclear and, ultimately, unimportant; what matters is that his story, as he says, “may be useful to those into whose Hands it may fall, for the guiding themselves in all the Extravagancies of their Passions” (19). If it also serves England’s colonial interests, who will say him nay?

Rutgers University, Camden

The author is grateful to Gabriel Cervantes for his comments on an earlier draft of this essay.

NOTES

i Defoe quotes the line, “For sudden Joys, like Griefs, confound at first,” from Robert Wild’s “Dr. Wild’s Humble Thanks for His Majesties Gracious Declaration for Liberty of Conscience” (1672), a satirical poem on Charles II’s Declaration of Indulgence that plays on the twinship of joy and grief. See Sill.

ii For the mentions of “joy,” “joys,” “joyful,” “grief,” “griev’d,” and “sorrow” in Robinson Crusoe, see Spackman 355, 434-5, and 804.

iii For a reading that locates the Portuguese captain within Crusoe’s economic history, but does not attempt to explain his extraordinary charity, see Freitas 453-9.

iv Crusoe, born in 1632, first speaks to his father (and mother) about leaving home at the age of 18 (RC 8). He leaves home “almost a Year after this,” on September 1, 1651 (9). His first voyage to Africa, which includes a long illness and several trading excursions, requires about a year (17). On his second voyage, he is taken into slavery by a Turkish pirate from Salé (or “Sallee”), from whom he escapes “after about two Years” (19). His rescue a month later by the Portuguese captain thus occurs in 1654. The significance of that year in Anglo-Portuguese relations suggests that Defoe chose the dates of Crusoe’s voyages and shipwreck not for autobiographical, but for historical reasons.

vC. R. Boxer attributes the decline in English shipping to Brazil through Portugal from 1650 to 1654 to this “undeclared war” (“English Shipping” 213). A treaty with articles governing trade was “dictated” by Cromwell in 1654, the year in which Crusoe was picked up at sea, and ratified (reluctantly) by King John IV in 1656 (210-15). Trade relations between England and Portugal were strengthened by the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and his marriage to Catherine of Braganza in 1661 (217-18).

vi See also the timelines for 1655-57 at the British Civil Wars Project: http://bcw-project.org.

vii For the difference in rigging of the caravel and the carrack, see Boxer, The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 27-8, 207. See Fig. 1 for an illustration of both the caravel and the carrack.

viii The two commandments of Moses are found in Deuteronomy 6.5, “you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and will all your might,” and Leviticus 19.18, “you shall not take vengeance or bear any grudge against the sons of your own people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself,” as well as Leviticus 19.33, said of a stranger, “you shall love him as yourself; for you were strangers in the lands of Egypt.”

ix English voyages between Africa and Brazil that did not pass through Lisbon were “commonplace” by 1657, but were conducted outside the Asiento, and thus illegal (Boxer, “English Shipping,” 213). For the Genoese contract, see the Schimmel Archive at the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society & Historical Museum: www.melfisher.org/schimmelarchive/exhibit3/e30011a.htm.

x G. A. Starr points out that “at the time of his captivity and escape [Crusoe] is blind to the agency of Providence in his affairs” (Starr 86-7). We may add that, even after his conversion on the island, he remains blind to the persons in whom Providence is represented, though he is aware of the role of Providence itself.

xi Whether Defoe himself held these prejudices is a difficult question. Most commentators are cautious not to attribute the views of fictional characters to Defoe. Paul Dottin, however, writes that Defoe believed that the Portuguese were a “mongrel race, exhibiting all the vices of the whites as well as the negro” (30).

xii A similar argument is made in Defoe’s A New Voyage Round the World, 210-12.

xiii Defoe’s low opinion of Portugal’s prowess at arms is shared by modern historians, such as C. R. Boxer, who finds that Portuguese soldiers and sailors in the seventeenth century were “only too often forcibly recruited from gaol-birds and convicted criminals” who lacked the most basic elements of discipline and military training, worsened by an “overweening self-confidence” (Boxer, Portuguese Seaborne Empire 116-7). Boxer, however, notes that color-based racial prejudices often affected the public perception of Portuguese soldiers and sailors (215).

WORKS CITED

Boxer, C. R. “English Shipping in the Brazil Trade.” The Mariner’s Mirror: The Journal of the Society for Nautical Research 37.3, January 1951, pp. 197-230.

—. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415-1825. New York: Knopf, 1975.

Defoe, Daniel. The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Edited by W. R. Owens, Pickering & Chatto, 2008.

—. The Life, Adventures, and Pyracies, of the Famous Captain Singleton. Edited by P. N. Furbank, Pickering & Chatto, 2008.

—. A New Voyage Round the World. Edited by John McVeagh, Pickering & Chatto, 2009.

—. A Plan of the English Commerce. Political and Economic Writings of Daniel Defoe, vol. 7. Edited by John McVeagh, Pickering & Chatto, 2000.

—. A Review of the Affairs of France. Edited by John McVeagh. Pickering & Chatto, 2003.

—. The Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. Edited by Thomas Keymer, Oxford UP, 2007.

Dottin, Paul. The Life and Strange and Surprising Adventures of Daniel De Foe. The Macaulay Company, 1929.

Freitas, Marcus Vinicius de. “The Image of Brazil in Robinson Crusoe,” Portuguese Literary and Cultural Studies 4-5, Spring-Fall 2000, pp. 454-9.

King James Bible, Revised Standard Version. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. Edited by Herbert G. May and Bruce M. Metzger, Oxford UP, 1977.

Miller, Christopher R. Surprise: The Poetics of the Unexpected from Milton to Austen. Cornell UP, 2015.

Napier, Trevylyan M. “Robert Blake.” The Naval Review XII no. 3, August 1925, pp. 399-433.

Novak, Maximillian E. Daniel Defoe, Master of Fictions. Oxford UP, 2001.

Potkay, Adam. The Story of Joy: From the Bible to Late Romanticism. Cambridge UP, 2007.

Roukema, Riemer. “The Good Samaritan in Ancient Christianity.” Vigiliae Christiane 58.1, Feb. 2004, pp. 56-74.

Sill, Geoffrey. “The Source of Robinson Crusoe’s ‘Sudden Joy’.” Notes and Queries 45.1, 1998, pp. 67-8.

Spackman, I. J., W. R. Owens, and P. N. Furbank. A KWIC Concordance to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Garland, 1987.

Starr, G. A. Defoe and Spiritual Autobiography. Princeton UP, 1965.