Abstract: R.F. Kuang’s bestselling 2022 fantasy novel, Babel, is set in the years leading up to the Opium Wars and chronicles the story of a Cantonese boy who is ferried to Oxford to learn the art of translation—and eventually discovers that his academic work is a tool used by the British imperial project. Kuang’s main character names himself after his favorite writer, Jonathan Swift, and the novel takes on a queer structure that aligns with Swiftian logic. This article examines this transhistorical intertextuality and reads both Swifts together. In so doing, and drawing from queer and Asian American studies work on “sideways”ness, this article argues for a sideways reading practice. This reading practice, the article theorizes and demonstrates, orients the reader obliquely to the text, accounts for narrative nonlinearity, asides, and marginalized perspectives, and challenges the more normative, imperial systems of signification these texts initially seem to propose and ultimately refute.

Keywords: Kuang, R.F.; Swift, Jonathan; queer studies; transhistorical; Asian American Studies; decolonization; decolonizing narratives

翻译: A Sideways Introduction1

CATHY PARK HONG talks about not looking back on growing up Asian in America but looking sideways, a riff on the phrase used by Kathryn Bond Stockton, who theorizes growing up queer. For Hong, looking sideways at childhood means that, “when I look back, the girl hides from my gaze, deflecting my memories to the flickering shadow play of her fantasies” at the same time it means “giving ‘side eyes’” that signify “doubt, suspicion, and even contempt” (68). Looking sideways contrasts and challenges the typical white teleology of childhood that moves from innocence to experience. The Asian child in America can never be innocent, as they are always made aware of shame, of not belonging.

I have often thought about my relationship to the field of eighteenth-century British studies as a sideways one, my experiences as a Chinese American scholar in the discipline marked by obliqueness. On a personal level, by studying this literature in graduate school, I was obliquely exploring my questions about identity and form (social, academic, literary). Frances Burney’s and Jane Austen’s works were prisms through which I peered in order to reach some deeper understanding of myself and my forays into literary studies.2 At first glance, it would seem that eighteenth-century studies was a way to “safely” explore questions about identity and otherness at a distance—rather than, say, specializing in Asian American Studies, diaspora studies, refugee studies. If I was talking about Burney and her characters, I thought, I didn’t have to talk about my own otherness—just Burney’s, Evelina’s, Cecilia’s, and so forth. If I became exceptionally good, my younger self thought, at literary analysis in English, then no one could question my belonging here—in the classroom, in the country, in the discipline.

Of course, that safety did not exist, for as I was working on my dissertation to complete my doctorate in English, the pandemic happened, and anti-Asian rhetoric rose around me. And just as much as I wondered what I was doing there in the British eighteenth century, white academics asked me what I was doing there. Several times, they assumed I specialized in Korean Studies or History (I did not and do not). Even at the most welcoming academic conferences, especially as a young graduate student, I felt very much the outsider peering in, trying to access conversations at side angles (sometimes literally, quite conscious of how tangential to conversational formations I was). Aside from my own oblique orientation to the texts, there was my obliqueness of positionality in the field.

In R.F. Kuang’s 2022 alt-historical fantasy novel, Babel; or, the Necessity of Violence, set in the years leading up to the first Opium War, a young Cantonese boy is ferried away from his home by a British man named Professor Lovell, and enrolled in Babel, a fictional Oxford school for translational studies. There, the boy learns the art of translation in order to master the magic of silver bars which power the British empire. Silver bars are etched with translation match-pairs (for example, the word for speed in English is written on one end, while the word for speed in another language is written on the other, and these bars are used to make naval ships travel faster, operating on the linguistic and conceptual gaps between the match-pair). The boy, whose first language is Cantonese, is an especial asset to the school, since languages like Latin and Greek are losing their magical translational power and the British Empire must “acquire” more languages to maintain their colonial footholds. The boy begins his school days enamored with academia and the wonders of community and intellectual inquiry it offers, but grows appalled and disgusted as he realizes the academy’s ties to—indeed, fueling of—the imperial project, and how his work has been used to enable the colonial horrors he witnessed as a child.

In this essay, queer and Asian/Asian American studies compound on each other, holding the potential to work in tandem to challenge the normative scripts forwarded by colonialism. Howard Chiang and Alvin K. Wong write,

Beyond the shared value in ambivalence, theoretical openness, and indeterminacy, one advantage in stressing the critical alliance between “queer” and “Asia” lies in their mutual transformative potentials in overcoming some of the enduring blind spots in each of their cognate fields of scholarly inquiry. If queer theory needs Asian studies in order to overcome its Euro-American metropolitanism and continual Orientalist selective inclusion of Asia and the non-West into its self-critique, so too can Asian studies revitalize itself through the queer disentanglement of the older version of “area studies” and its complicity within the nation-state form. (“Asia is Burning: Queer Asia as Critique”)3

Babel queerly toggles between Guangzhou and Britain, and runs between being about academia’s past and academia’s present, about (not) being a colonial subject and (not) being a model minority. A book about queer Asian diasporic characters and colonialism—that actively incorporates the works of eighteenth-century authors such as Swift—calls to be read through a combination of lenses. With these multiple lenses, I argue that Swift’s obliqueness and Kuang’s narrative strategies implode the storyworlds they construct as well as systems of signification they initially seem to establish, and therefore offer us an answer to our question of how we may go about decolonizing our field. Both, in other words, ask us to inhabit a sideways positionality—to the text and to the discipline of literary studies, challenging preconceived, scripted notions of subjecthood and the work we do in the academy.

Of interest to me in this essay is that the boy in Babel names himself Robin Swift—after his favorite writer, Jonathan Swift. This essay will explore the narrative effects of this intertextuality. In doing so, I am not trying to establish a one-to-one relationship between the two Swifts; rather, I am performing what Helen Deutsch calls “a mode of reading that responds to and re-animates the writers who make demands on us without erasing or taming their otherness” (“We Must Keep Moving”), which I believe is exactly what Kuang is doing by making these allusions to long eighteenth-century literature and by setting Babel in the long eighteenth century. I argue that, through the narrative’s engagement with Swift and the narration’s toggling between editorial, narratorial, and authorial voice, Babel presents obliqueness as a way to talk about Asian diasporic identity, colonial subjectivity, and queerness. It thereby presents obliqueness as an inevitable position of the marginalized in academia, but also, perhaps, as a site and method for anti-colonial revolution. The book’s narrative strategies (mainly, footnotes or asides) formally challenge readerly attempts to “master” or “pin down” the work, and, for both Swifts, these formal destabilizations also topple storyworlds. In this way, reading for sidewaysness in Swift and Babel—and orienting obliquely to the text—makes visible the anti-colonial form and message of both. Kuang and Swift do not offer us complete closure or readerly mastery over their texts; instead, they encourage us to think about what happens when our default (perhaps, colonial) hermeneutics are no longer viable, and leave open new possibilities for reading practices, theorizing canonicity, thinking about the relationship between academia and (anti-)colonialism.

Swift, and Swift

The novel makes a diegetic detour into Gulliver’s Travels at one point, comparing Robin’s eventual return to Guangzhou after years in England with Gulliver’s eventual return to his family following a voyage to the Houyhnhnms. Gulliver no longer knows if he is more human or Houyhnhnm, and Robin is no longer sure of where his political allegiances lie.

Though Gulliver’s is invoked by the text, Babel also parallels Swift’s scatological poems, by proposing a subject and narrator and then subverting the very positionalities of both, turning initial systems of signification on their head. Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room,” for example, emphasizes the queer blurring between subject and object, a creation of that sideways-ness. A “dirty Smock” appears to Strephon as if by its own agency (line 11), and he “turn’d it round on ev’ry Side” (line 12); what follows is a colon which suggests the smock will be described, but the speaker elides this as “Strephon bids us guess the rest” (line 16). Poetic opacity is as play here, and already objects in Caelia’s room have subjecthood. Another moment of blurring happens later:

But O! it turn’d poor Strephon’s Bowels,

When he beheld and smelt the Towels;

Begumm’d, bematter’d, and beslim’d;

With Dirt, and Sweat, and Ear-wax grim’d. (lines 42-45)

Because of the semi-colons and the placement of the adjectives, an argument can be made for “Strephon’s Bowels” being the antecedent to “begumm’d, bematter’d, and beslim’d” just as much as Caelia’s towels may be. What is outside Strephon’s body is now inside; what is inside Caelia’s body is now outside. There is a blurring of subject and object. What might seem on the surface as a misogynistic poem about the lewdness of women’s bodies is, rather, about Strephon’s realization that bodies are permeable and categories fluid (pun intended). He is the subject of the poem, as well as the object of satire.

In a productive transhistorical move, Julia Ftacek finds resonances between Jonathan Swift’s and Taylor Swift’s artistry, which both blur the distinction between author and reader: who is being read, really? Ftacek writes about queerness, transness, and asexuality, and what unites these elements in both Swifts’ work—a knowledge of the reader.

The brilliance of both artists is clear, then. They know their audience, know us. We are a people who gaze, who guess, who try to pin down identities. Jonathan and Taylor live (or did live) their lives under the weight of a thousand stares. But when we start to see them together, these Two Swifts, that’s when we start to understand that we voyeurs are also the obsessed. Jonathan and Taylor, the Two Swifts, always gazing back (Ftacek, The Rambling).

By gazing back, like Derrida’s cat,4 the two Swifts put into question readers’ assumptions, our sense of our own subjectivity, our seeing I (read: eye). Swift’s satirical power lies in this ability to inhabit our assumptions—about narrative form, about gender, about allonormative scripts—and to turn these assumptions back upon us.

In Paddy Bullard’s account of Swift’s theorization of his own satire, razors and knives are a common centralizing metaphor. They cut, they dissect, they examine and dig, they hurt and heal. “Swift’s blades often represent a finely balanced conceptual tension: acuity runs into bluntness, edge is poised against surface, or, occasionally and more positively, incisive violence is mitigated by accomplished tact” (3). Aggression, anger, and precision of thought are all combined and finely-tuned in Swift’s satire, and, I would add to Bullard, a deft movement from inside to outside, and between inside and outside. That is, in order to enact such a scathing (violent) satire, Swift cuts in.

Babel makes Swiftian incisions into the workings of academia, and it does so through its main character, Robin. Robin goes through the same defamiliarization that Swifts’ readers go through, and also, toward the end, has the same effects that the Swifts do. He is both the object of satire in the book when it comes to his loyalty to academia, and the satirist once he awakens to the paradoxes of academia, which fetishizes him and his translational labor just as it needs him to survive. To the first: at the start of his Oxford journey, Robin is enamored by certain aspects of academic work: community, intellectual pursuit, an illusory sense of belonging. But when he encounters a rebel on the street stealing from Babel—a boy who is his “doppelganger”—the result is uncanny. He learns that this boy is his half-brother who the professor (their biological father, they deduce) also put through schooling, and Robin begins to see 1) that he himself is a cog in the machine, a repetition of the status quo of the empire and 2) that there is an alternative path to the one he’s on.

To the second, Robin is a satirist himself, especially as he realizes he will never be loved by England or his biological father, and that both England and his father have been the source of his and many others’ suffering. After Robin’s diplomatic trip to Canton as a translator is followed by Lin Zexu setting chests of opium on fire, Professor Lovell questions Robin’s loyalty and calls him ungrateful. For the first time, Robin questions back: “‘Did you think,’ said Robin, ‘that enough time in England would make me just like you?’” (319). When Professor Lovell responds with racist remarks about how “‘there is no raising you from that base, original stock’” (320), and refuses to call Robin’s Cantonese mother by name other than a racist slur, Robin kills him with a magic silver bar obtained from his half-brother, Griffin. He “spoke the word and its translation out loud…Bào: to explode, to burst forth with what could no longer be contained” (322). Robin is Jonathan Swift’s razor literalized, harnessing the pain, anger, and rage of his mother, his half-brother, and himself to turn against the academy—and through the academy, the empire.

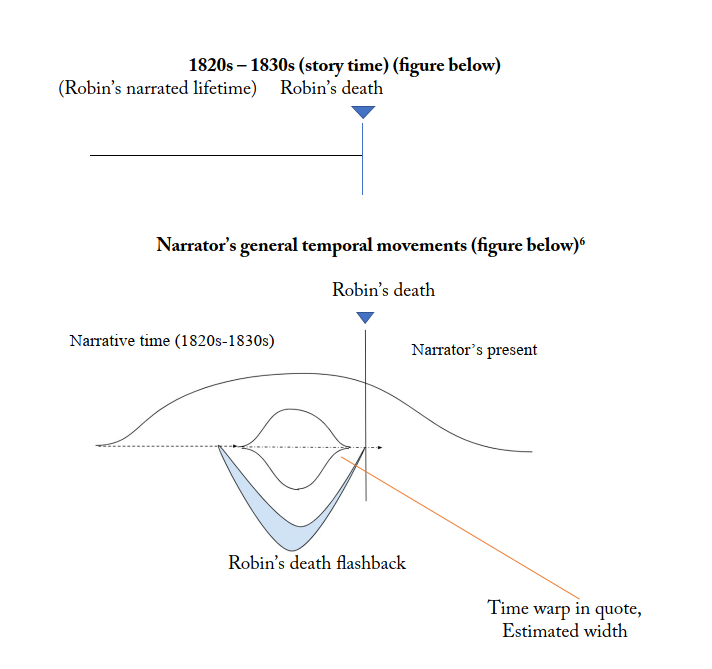

The queer narrative style allows Robin to be both of his diegetic time, bookended on either side by death—his mother’s and then his own— and of a time beyond his own. There are moments when the narration in story time leaps forward to a future Robin—impossible because he is dead at the point of narration, it is suggested, but there nonetheless. For instance, when Robin’s first formative encounter with his future best friend and love interest Ramy is described, the narrator interjects: “In the years to come, Robin would return so many times to this night” (51), painting a brush stroke that suggests many years to come when, really, Robin has only a handful of years left to live. When Robin murders his father, the narrator slows time down and fast-forwards it simultaneously: “Afterwards, Robin wondered often if Professor Lovell had seen something in his eyes, a fire he hadn’t known his son possessed…Over and over again he would ask himself who had moved first” (321). And in the last chapter, as Robin dies in the collapse of Babel, the narration creates a new section and reads: “He went back to his first morning in Oxford: climbing a sunny hill with Ramy, picnic basket in hand…The air that day smelled like a promise, all of Oxford shone like an illumination, and he was falling in love” (535).5 In a rather eighteenth century move, I will attempt to illustrate the general idea of the queer narration here:

Robin cuts through systems of power and through linear time. Put another way, Robin as a protagonist demonstrates that a teleological narrative (from uncivilized to civilized, from innocence to experience) is a colonial construct. He destabilizes, queers these categories, leaving open a gap in time and interpretation that escapes linearity—opening out the narrative to readers, a space where he might live on.

Shifting Narration & Footnotes as Destabilizing Narrative Technology

Kuang’s narrator is not interested in strict linearity and is not a static persona. At times, the third-person narration is distant and fairytale-esque, telling us of the events in sweeping historical gestures. At other times, we are inside Robin’s head in typical free indirect discourse fashion. Other times still, we are clued into future Robin’s reminiscences about the present story-time moment, but this, as previously mentioned, seems improbable and confusing as he dies at the end. The scale of the timeline of the narrator’s knowledge, then, shrinks and expands depending on the moment.

The novel also makes frequent and interesting use of footnotes, some of which are historical (“Thomas Love Peacock, essayist, poet, and friend of Percy Bysshe Shelley, had also enjoyed a long career in India as an official with the East India Company” [390]); others which are etymological and in line with the translational work of the characters (“Thief’s slang for a gaoler [jigger meaning ‘door’, and dubber meaning ‘closer’]” [129]); others which are fantasy worldbuilding (“The Hermes Society also had connections with translation centres at universities in America, but these were even more repressive and dangerous than Oxford” [383]); and others still which are infused with what seems to be authorial, essayistic perspective (“This is true. Mathematics is not divorced from culture. Take counting systems—not all languages use base ten” [105]). In Romantic Period literature, paratext was, as Ourania Chatious has argued, quite commonly used: “The division between ‘letters’ or literature and factual writing was not securely in place—the former might include travel and biography, for instance—and that is partly why footnotes and/or endnotes could be and were used in such writing. Romantic writers thus imaginatively exploited this liminal moment before the genres were more precisely defined and annotated fiction became an oddity” (640). It was not only Byron, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Southey who employed what Chatious refers to as “liminal” generic tools; Charlotte Smith, for example, among other women poets, used footnotes to various ends. Women poets could undercut masculine empiricist knowledge by employing footnotes to establish their own authority (Knezevich 1); to open a poem up to transhistorical, intertextual possibilities, thus exploring the slipperiness between absence and presence (Huerta, Poetry Foundation); and to use footnotes as a form of gender play (Jacqueline Labbe 167). In all these accounts, footnotes productively interrupt the textual narrative such that univocality is no longer—or revealed never to have been—possible.

Babel’s frequent use of footnotes creates the effect of a narrative constantly being destabilized. In line with the sideways reading practice I’m proposing here, we can think about these footnotes as asides. Elaine Freedgood’s account of eighteenth-century novelists’ footnotes argues that notes “create a sort of side relationship between narrator and reader” (399) and “ask us to think about where we are reading from, and where we go when we read, and about how the type(s) on the page take us to these various levels of [temporal and geographical] frames, and how we know or can know what level or space we are in at any given moment” (400). Footnotes serve to put the story time and space in conversation with the reader’s time and space. Thus, Babel and its use of footnotes create a tale that is not able to exist stably as a story about one singular boy; other relationships are at play as well.

Perhaps ironically, the footnotes (typically viewed as scientific and factual) remind readers that the book is not a history, but an alt-historical fantasy, that it crafts a space between historical fact and fiction. In Freedgood’s words, “the realistic novel creates an open circuit between fictionality and factuality, between fiction and history, and thus gives us the choice fiction or history” (408). Babel presents itself as a refraction of historical and sociopolitical truth but, importantly, not historical fact proper: it is important that one such as Robin could have existed, but that he was not a real person. The footnotes drive a wedge through the pages so that readers tempted to read a book written by a woman of color as an autobiography or as a textbook about Chinese culture writ-large do not and cannot read it that way.7 This is a particularly eighteenth-century footnote effect: Freedgood writes that “metalepsis in the form of the footnote insists that what we are reading may be based on other texts, but those other texts may also be fictional. The basis of historical belief is undermined; realistic fiction is of course also thoroughly bedeviled” (400). Yet, the eighteenth-century novelists in Freedgood’s account employ footnotes to colonial ends: “The collecting of data…holds together an empire and makes space imaginable and then readable, and then, finally, physically inhabitable” (404). In contrast, Babel employs footnotes to anti-colonial, destabilizing ends, and is actively invested in “social, historical, and psychological probability and truth” (Freedgood 400)—but sets reading for these truths markedly apart from reading a work of fiction by a writer of color as purely historical truth. This interpretation is buttressed by the sad fact that Kuang felt the need to write a preface that anticipates such arguments:7 “Some may be puzzled by the precise placement of the Royal Institute of Translation, also known as Babel. That is because I’ve warped geography to make space for it. Imagine a green between the Bodleian Libraries, the Sheldonian, and the Radcliffe Camera. Now make it much bigger, and put Babel right in the centre. If you find any other inconsistencies, feel free to remind yourself this is a work of fiction” (xii).

The footnotes ultimately allow Kuang to claim an authorial form of narration and annotation utilized by Byron in his Orientalist work, and encourage a reading practice that cues readers into the scathing satire of Babel, bringing readers into the seemingly warm embrace of academia before plucking them out of it. Even as the narration details Robin’s sense of infatuation with academia, the footnotes interrupt and maintain critical distance from the narration proper, serving as reminders that the novel as a whole (and, indeed, the older Robin) does not endorse this infatuation. The footnotes, in other words, topple the hierarchy of narrative power onto its side, keeping readers empathetic to how tempting it is for Robin (and readers) to subscribe to the system while also keeping readers aware of the dangers of this temptation. We are supposed to trust the authority of the footnotes—as products of research coming from a narrator and author who have clearly done the research— and, at the same time, not trust the footnotes—as annotations that operate on the authority of the academy in what is not a purely historical text. We are meant to, in other words, have a sidelong relationship with the text, to become better critics ourselves.

Savage Indignation

The paradox of the academy is that it fetishizes Robin just as its very survival depends on him and his labor. The paradox of a fetish is that it makes him feel special just as it erases his humanity. What does resistance look like in the web of all these paradoxes? Babel ends with a strike. Robin and his friends (notably, not his white feminist friend, who has betrayed them all to the authorities and even shoots one of them) take over the tower by force and choose to blow it up by using the magical silver bars that fuel the empire and keep the tower standing. In the book, the one rule of translation is never to use the silver bar match-pair for the word “translate,” because translation works on paradox, and professors theorize that such an unstable match-pair could have disastrous effects. Robin implodes the bars with the match-pair for the word “translate” and the tower of Babel collapses around him. Robin Swift unearths Jonathan Swift’s “savage indignation,” a phrase which comes from the latter’s epitaph, which was originally composed in Latin and needed to be translated.9 It is this type of rage that explodes forth and implodes structures.

Institutions built on paradoxes do not have strong foundations. In a rather acerbic satirical—Swiftian—fashion, Robin makes stark the unsustainability of the academy and the academy’s role in empire. It is a bleak ending, but it is not entirely without hope: there is a sort of relief in Robin’s realization that the academy and England will never love him, no matter what he does; there is a relief in his refusal to be a docile colonial subject, to be what the professor raised and conditioned him to be; there is also a relief in finding his true friends and community who will fight, struggle, and rejoice alongside him.

The message of Babel reminds me of a line in Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room”: “No object Strephon’s Eye escapes.” Read one way, Strephon’s eye has no chance of escape from any of the objects in the room that haunt him: these objects act upon him, making him the one without agency, entrapping him. He is not supposed to be there, and he is enamored and overwhelmed by the novelty (and the horrors) of all he sees. Yet, read another way, the line seems to convey the very opposite: that Strephon’s eye has agency and can see each and every object— none of the objects can escape his eye. This is a line that necessitates a sideways reading, a toppling of order, and an inclusion of marginal perspectives. When being gazed at, when caught in environs that invoke both attraction and disgust, Robin Swift and Jonathan Swift urge us to gaze back, to inhabit that queer position for just a little longer, to analyze the systems that surround us, that we find ourselves in, sideways and from a distance, in order to see systems of power for what they are—and, ultimately, to implode the paradox upon which they operate.

Los Angeles, California

Notes

1 Mandarin for “translate.” 翻 fān means to turn upside down or inside out; to look through; to reverse; to cross; to multiply; to translate, in that order. 译 yì means to translate; interpret; decode.

2 I write more about this in “Ingénue Reading Ingénue.”

3 Although what I am doing here is drawing primarily from Hong’s work on Asian America, I too am taking Chiang and Wong’s mode of theoretical confluence a step further.

4 See Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am.

5 The “and” does a lot of beautiful rhetorical work in this sentence, driving a space between Oxford and the fact that Robin is falling in love—importantly, not with Oxford, but with Ramy.

6 Unlike Tristram Shandy’s figures, I doubt this one will show up as a tattoo on even the most avid eighteenth centuryist.

7 See the #ownvoices controversy.

8 This is a disclaimer I have seen more and more often in fantasy books by Asian authors. Xiran Jay Zhao, for example, wrote in a preface to Iron Widow (2020): “This book is not historical fantasy or alternate history, but a futuristic story set in an entirely different world inspired by cultural elements from across Chinese history and featuring historical figures reimagined in vastly different life circumstances. Considerable creative liberties were taken during the reimagining of these historical figures, such as changing their family upbringing or relative age to each other, because accuracy to a particular era was not the goal. To get an authentic view of history, please consult non-fiction sources” (Disclaimer page).

9 The full epitaph reads:

“Swift has sailed into his rest;

Savage indignation there

Cannot lacerate his breast.

Imitate him if you dare,

World-besotted traveller; he

Served human liberty.”

Translated by William Butler Yeats in “Swift’s Epitaph,” in The Poems of W. B. Yeats, ed. Richard J. Finneran. Macmillan, 1983.

Works Cited

Bullard, Paddy. “Swift’s Razor.” Modern Philology 113 (3), pp. 353-372. Doi.org/10.1086/684098

Chatsiou, Ourania. “Lord Byron: Paratext and Poetics.” The Modern Language Review, Vol 109 no 3, July 2014, pp. 640-662.

Chiang, Howard & Alvin K. Wong. “Asia is Burning: Queer Asia as Critique.” Culture, Theory and Critique, 58:2, pp. 121-126. DOI: 10.1080/14735784.2017.1294839

Derrida, Jacques. The Animal That Therefore I Am. Fordham University Press, 2008.

Deutsch, Helen. “We Must Keep Moving.” The Rambling. August 7, 2020.

Freedgood, Elaine. “Fictional Settlements: Footnotes, Metalepsis, the Colonial Effect.” New Literary History, vol. 41, no. 2, 2010, pp. 393-411. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40983828.

Ftacek, Julia. “Jonathan and Taylor: The Two Swifts.” The Rambling. February 13, 2021.

Hong, Cathy Park. Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. Penguin Random House, 2020.

Huerta, Javier O. “Ghosts in Charlotte Smith’s Elegiac Sonnets.” Poetry Foundation. October 31, 2008. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/2008/10/ghosts-in-charlotte-smiths-elegiac-sonnets.

Knezevich, Ruth. “Females and Footnotes: Excavating the Genre of Eighteenth-Century Women’s Scholarly Verse.” ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830, vol. 6, no. 2, Fall 2016.

Kuang, R.F. Babel; or, The Necessity of Violence. HarperCollins, 2022.

Labbe, Jacqueline M. Charlotte Smith: Romanticism, Poetry and the Culture of Gender. Manchester University Press, 2003.

Stockton, Kathryn Bond. The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century. Duke University Press, 2009.

Swift, Jonathan. “The Lady’s Dressing Room.” The Essential Writings of Jonathan Swift, edited by Claude Rawson and Ian Higgins, W. W. Norton and Co., 2010, pp. 603-606.

Zhao, Xiran Jay. Iron Widow. Penguin Teen Canada, 2021.