ORCID: 0000-0002-9981-2740

Abstract: Because pirate tales as a genre are intensely intertextual and counterfictional, it is often befuddling when the historical record will not align with historical fiction. While it is assumed pirates may well have used prosthetic hooks, there is little reason to believe J. M. Barrie’s memorable villain wore a hook as an informed piece of historical continuity. What evidence we have as to the use of hook prostheses connects them to the laboring classes, not the Eton-trained menace of Jas. Hook and his iron appendage, and there is virtually no evidence at all of pirates using hook prosthetics. Rather than attempting to locate the pirate’s hook in historical antecedents among real one-handed adventurers—neglecting the importance of how disability was understood both in Barrie’s time and earlier—the piratical hook is better understood as a loose signifier for the pirate’s social perversity.

Keywords: piracy; prosthetic; Captain Hook; Long John Silver; disability

Introduction

IT WAS PROBABLY J. M. Barrie who made hooks a stock item for murderous pirates. While one-armed sailors had long dotted the cultural seascape, before Captain Hook came along, the hook-wielding pirate was really not a trope. In discourse around pirates in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries (that is, the Golden Age of piracy, so called), pirates are often terrifying torturers, and are potentially the defilers of other bodies, but they are only rarely depicted as having been maimed themselves. Descriptions of historical pirates with prosthetics are vanishingly rare. In contrast, by the end of the eighteenth century, prosthetic legs and missing arms became an increasingly common sight due to warfare and the dangers of maritime work, both on the street and in print, at least in London and major port cities. In the nineteenth century, the presence and marginalization of disabled people continued to increase—because of industrial accidents and wars, but also due to improved medical treatments that meant more people could survive grievous wounds. This happened concurrently with a palpable increase in the middle-class anxiety to make bodies outwardly conform to a standard, status-signifying appearance. Barrie’s decision to have his villain eschew a more realistic artificial limb in favor of a weaponized hook was therefore a choice with both aesthetic and, for his audience, moral freight.

Hook, in fact, draws attention to his evilness through his willingness to underscore (sometimes actually by making score marks with) his disability. But the very familiarity of Hook’s choice—discordant as it might once have been—has made it indelible in the piratical cultural imaginary. Or to put it another way, different imaginaries are combined in the figure of the pirate: loss of limb (real) along with the politics (intangible) of what a body should look like in public. Modern readers remember Hook; historians tell us there were maritime amputations, and so arises a collective sense that this is what all pirates had: we grow to “remember” pirates as having hooks. It is not only fiction readers who build and flex these associative sinews, but authors and scholars, too. Pirate lore is founded on a relatively small, dubiously accurate, self-referential groups of texts, and so it is particularly crucial to examine the types of evidence—literary, cultural, documentary—that underpin what feels true about pirates.

A strong feeling of familiarity does not mean assumptions about the correspondence between historical fiction and historical materiality—fantasies about them—are meaningless or careless. Memory studies rose to prominence as a field of academic interest in the later nineteenth-century, which is the same period Stevenson and Barrie wrote their piratical masterpieces. Moreover, interest in the formation of cultural memories—their constructedness, rather than historical roots—in particular has become conspicuous in the field.1 Works such as Daniel Schacter’s influential Seven Sins of Memory warn us that humans can easily be misled into creating false memories by feelings of familiarity—such as the kind that comes from past stories, dimply recollected in more mature days.2 What I propose here is, essentially, that there is a powerful Mandela effect around pirate prostheses.3 Scholars argue that there is even a specifically visual version of the Mandela effect in which people are prone to remember the same specific wrong detail about familiar images.4 This resonates well with the piratical case study, in which the iconic pirate, who is usually missing at least one and usually more than one major body part, so readily appears in visual media of all kinds.

This essay unpacks the fictional roots of our cultural beliefs about pirates to show how their constructedness comes not only from history, but from creative forms as well. Because of this, we need to understand popular ideas of pirates in terms of disability: its realities but perhaps more importantly its shifting cultural resonances.

***

We begin not with the question of historical cases of pirate disability, although those will come, but with canonical ones. Connected to Barrie’s reshaping of old nautical tropes into newer piratical clichés is the association between Robert Louis Stevenson and pirate disability. One of the memorable verbal tics of Treasure Island’s clever, one-legged pirate Long John Silver is his oath, “shiver my timbers.” Silver’s shivering timbers are sprinkled liberally throughout the text, along with other nautical markers that assure the reader of the briny nature of the piratical dialog: for example, “Cross me, and you’ll go where many a good man’s gone before you, first and last, these thirty year back—some to the yard-arm, shiver my timbers, and some by the board, and all to feed the fishes” (148). Treasure Island (1881-2) has been a key source for what readers grow up thinking pirates looked and sounded like for more than a century, but Stevenson is rather a nexus than a source in the sui generis sense. He admitted openly to borrowing some of his pirate color from other writers, such as Washington Irving’s Money Diggers stories (1824), which influenced the scene at the Admiral Benbow Inn; he was also certainly influenced by the pseudonymous General History of the Pyrates (1724-8).5

“Shiver my timbers,” though, is not a literary invention, but instead an ambiguous theatrical trope for pirate talk. Its cloudy history ably demonstrates the multifarious sources for popular culture beliefs around piracy. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that the phrase “shiver my timbers” (that is, shatter my ship), was a fictional sailors’ oath invented in Frederick Marryat’s 1834 Jacob Faithful, a yarn about a Thames waterman (e.g., “I won’t thrash you, Tom. Shiver my timbers if I do”). But the phrase, which in context serves the same general purpose as, “I swear,” or “damn it,” was extensively used in song, story, and on the musical stage, for decades before Marryat turned his hand from reefing and steering to fiction. It appears, for example, in C. W. Briscoe’s Clerimont (1786), Mary Robinson’s Angelina (1796), in comic operas like Samuel Arnold’s The Shipwreck (1797), and in periodical pieces, such as “A Conversation between an English Sailor and a French Barber” (1796).

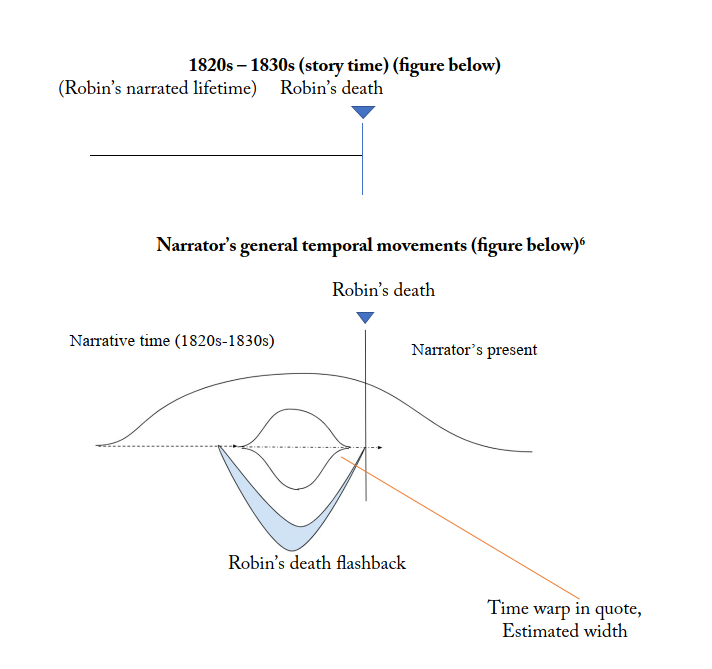

The 1800 image, “A Broken Leg, or, The Carpenter the Best Surgeon” [Figure 1] does really connect the phrase, as with Silver, to a mariner’s amputated leg. The sailor, Jack Junk, is intoxicated, and has fallen and broken his wooden leg; his companions waive off a doctor and instead hail a passing carpenter, explaining, “Jack … has shivered his Timbers—and wee [sic] want a Splice here.” The scene is comic, and notable for the cheerful good humor of its characters (even the woman looking on from the window appears to be gesturing knowingly, either in on the joke, or possibly picking her nose). Importantly, if the tableau mocks the disabled man, still there is no hint that he is sinister, a villain, or at all piratical.6 Shivering timbers, then, were a matter for the common mariner amputee, and only very belatedly for a more swashbuckling stereotype. Teresa Michals goes further by arguing that in contrast to the famous fictional pirates like Silver and Hook, up through the Napoleonic era, “the actual amputees who commanded tall ships were not villains. They were national heroes” (1). Michals’s study is of officer amputees, though, and the class status of even pirate captains is inevitably compromised, for a pirate officer may achieve wealth, fame, or notoriety, but cannot be treated as an acceptable member of the higher social classes.

Figure 1. [“A Broken Leg, or, The Carpenter the Best Surgeon,” 24 February 1800, Laurie & Whittle: 53 Fleet Street, London. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.]

It may indeed have been the popularity of Stevenson’s tale that transformed “shiver my timbers” from a comic oath and in-joke of a group of sailors we can see in “A Broken Leg, or, The Carpenter the Best Surgeon” to the indelible utterance of a one-legged buccaneer. But here an odd thing happens: the timbers of Silver’s oath became, in the foggy memory of Stevenson’s reader, the timber replacing his lost leg. Silver explicitly used a crutch in the novel, but is often depicted in prints and film with a different wooden prosthetic: an artificial leg. (The drama Black Sails [2014-17] campily gave him a silver leg that could be used as a bludgeon.)

Perhaps Silver is associated with wooden legs, despite his not wearing one, because he often uses language that was metonymically attached to the practice; memory is constructive this way.7 Indeed, Silver’s very dexterity, the combination of his charm and criminality, make it difficult to read his disability.8 Stevenson, author of so many travelogues and pirate yarns, understood the vicissitudes and joys of travel with an imperfect body. He was for long periods made an invalid by his experience with tuberculosis; he was directed to travel as a medical treatment at a time when climatotherapy often involved such piratical locales as Malta, Algiers, and the Mediterranean (Frawley 72-76).9 Therefore, both the historical record and Stevenson’s own experience underpin the plausibility of Silver’s wooden prosthetic, crutch or otherwise. However, legs whose loss is assisted by a wooden crutch or peg have been documented among maritime workers much earlier than the use of hook hands—and this is why this essay primarily follows Captain Hook’s hook instead of Long John Silver’s prosthesis.

This essay uses as its main case study the hook-using pirate, a figure often treated as historically plausible but for whom, it turns out, the evidence is scanty at best. But it is interested in wider questions as well: Why, when it comes to Golden Age [ca. 1650-1730] pirates, do we feel that things happened without good evidence that they did? How do we transpose ideas from popular media back into educational work and scholarly inquiry? It is no wonder, given the cultural ubiquity of pirate stories, that Anglophone readers grow up believing some things about pirates that are, to put it gently, not well supported by evidence. The histories we have relied on for hundreds of years, chief among them Captain Charles Johnson’s General History of the Pyrates, intermix fact, fiction, and speculation, but stories told and retold from that core set take on a force of their own; their truisms start to exist in the popular imaginary. For example, the basis for claiming that the pirate Mary Read hid her identity as a woman and called herself “Mark” while on board John Rackham’s ship, or that Edward Thatch (Blackbeard) set his beard alight while boarding other ships, is about as compelling as the basis for George Washington cutting down that cherry tree.10 (In other words: this never happened.)

Documented examples of known pirates who used hooks are hard to come by. It is at least clear that loss of limb was a hazard of regular maritime work, to say nothing of maritime warfare. Not only regular seafarers, but pirates and buccaneers, from Henry Morgan to Bartholomew Roberts, accepted this risk, and even provided for a form of insurance payments for maiming in their articles.11 In the 1935 film Captain Blood, this well-known trope is played for humor, when the pirate Honesty Nuttall shoots his little toe off in a futile attempt to increase his share of booty. Moreover, depictions of one-legged sailors are so common in the eighteenth century that it would seem only logical to assume that there could indeed have been peg-legged pirates stumping the deck here and there; images of one-eyed men are slightly less common but still readily available. The case for progenitors of Captain Hook, though, is dicier. In fact, a “real” Captain Hook is unlikely, or at a minimum, unproven. I suspect that, more often than is readily acknowledged, readers of history who are interested in piracy begin with a picture of Captain Hook as the primary impulse for imagining hook-using pirates, and work backwards from there, rather than the other way around. These two arguments together point to a peculiar property of pirate yarns to become unmoored in both genre and temporality. We tell tales about pirates because we want them to be true.

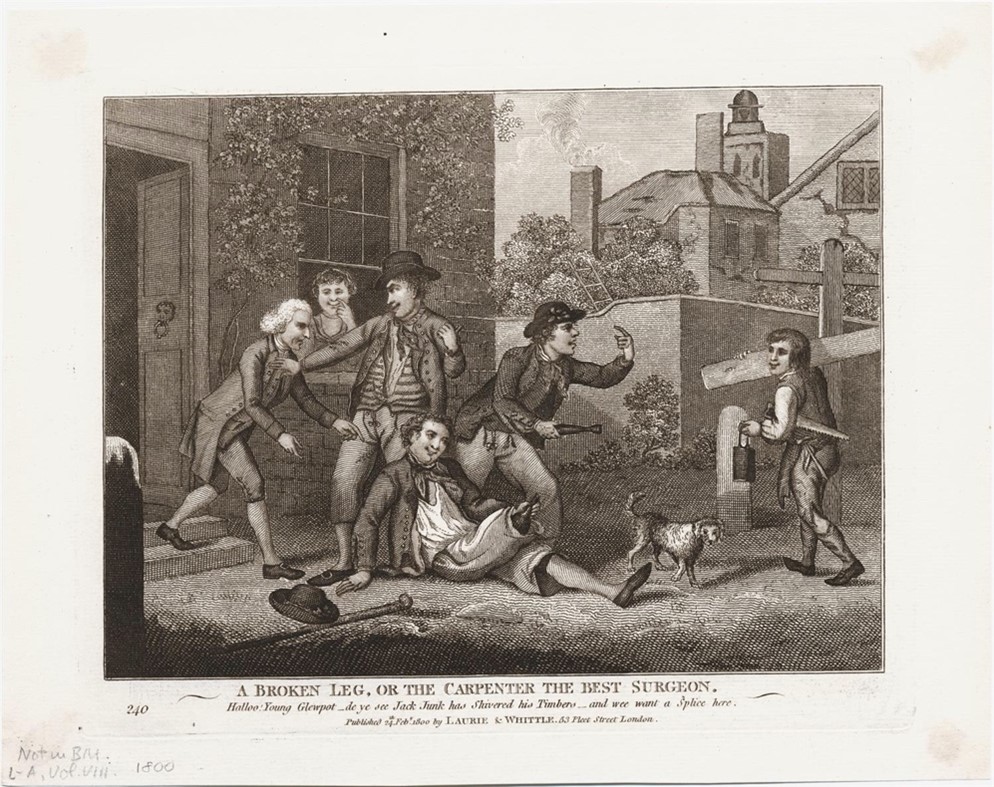

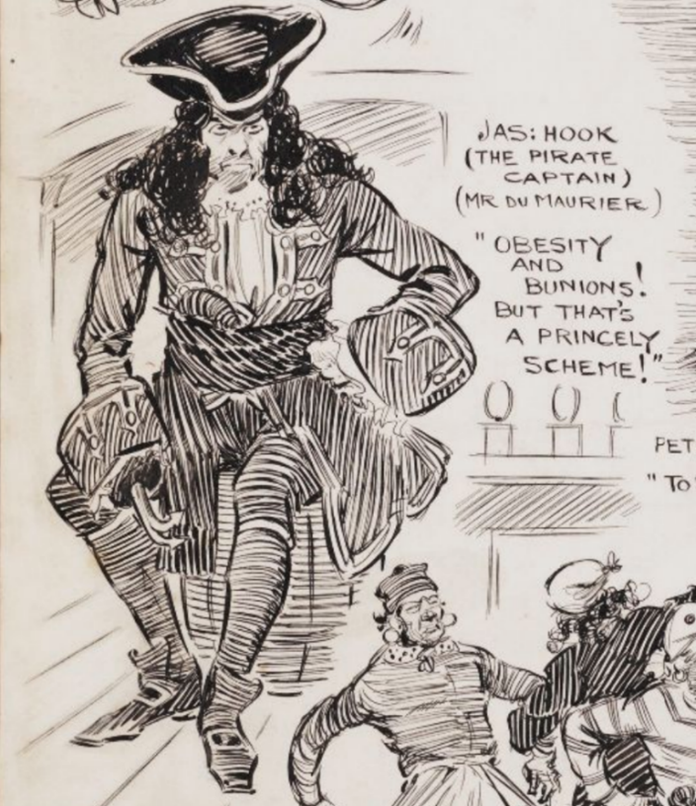

Here is the Captain Hook contradiction: while it is often assumed as a cultural truism that pirates did use prosthetic hooks, J. M. Barrie’s memorable villain did not wear a hook as a nod to historical continuity. Hook’s hook is improbable either as a late Victorian or a Golden Age accessory; it must be a fictional invention, and not one meant to invoke some kind of gritty realism. As Ryan Sweet points out, prior to Captain Hook, even literary depictions of pirates using hook prosthetics were uncommon (Sweet, “Pirates and Prosthetics” 87-88).12 The evidence we have as to the use of hook prostheses connects them more to the laboring classes than the aristocratic, Restoration fashion-wearing terror of Jas. Hook and the iron appendage that replaced his organic thieving fingers. [Figure 2] A number of critics have already traced the fictional antecedents that influenced Barrie; Jill P. May helpfully makes clear the attachment of Hook and his band not only to Marryat, Fenimore Cooper, and Stevenson, but also to Gilbert and Sullivan and the musical tradition of comic singing pirates they crowned in 1879 with The Pirates of Penzance (70).13 Yet none of these ancestral buccaneers satisfactorily explains Hook’s appearance. My suggestion is that Hook’s hook might be best understood as a loose signifier for Hook’s perversity. Speaking more broadly, it would do us no great harm to be suspicious of whether the foundational pirate fiction writers like Fenimore Cooper, Marryat, Stevenson (all of whom had at least some claim to expertise on the maritime world in general), or Barrie (who has become as influential as the rest) had any particularly deep knowledge about pirate history.

Figure 2. [Detail from a sheet of nine illustrations by Frank Gillett (1874-1927) from the 1905 production of Peter Pan. Beinecke Library, GEN MSS 1400.]

I. Histories of the mariner’s missing hand

“Canonical” historical fiction about pirates does not align with the historical record. This may seem obvious, but the collective attachment to pirate lore overwhelms evidence time and again. (E.g., people persist in hoping to find buried treasure on Gardiner’s Island and Oak Island.14) It is difficult to find evidence that the hook prosthetic was in wide use among amputees at all, piratical or otherwise, prior to the nineteenth and perhaps the twentieth century. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but it does make it far from likely that Barrie’s detail about the hook was intended as historical verisimilitude, and it was not a direct literary allusion, either. What was true? This section will provide an introductory primer on the discourse around sailors’ manual amputations and how society did and did not make room for them. Missing limbs were real enough, and considerable thought was devoted as to what to do about them—but early on, the hook prosthesis is mostly absent from that discourse, which focuses on compensation and employment prospects, as well as occasional attempts at creating lifelike prostheses.

The immediate consideration was what was to become of the impaired man and his dependents. A naval sailor who was severely injured by his service could apply for a pension or, after 1705, for a spot in the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich.15 Civilian companies were often willing to take some steps to care for employees injured on the job, even as early as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and there were various charitable institutions who undertook to help provide for the impaired as well; those harmed in the course of employment could make a case for belonging to the category of the so-called deserving poor. At the same time, a history of employment and a continued willingness to work were strong prerequisites for receiving such aid, as Haydon and Smith have noted (54-55; 59). They provide the striking example of Thomas Joyce, a clerk in the employ of the British East India Company, who lost a hand when it was “cut off by an Arabian at the siege of Ormuz,” but learned to write with his left hand and petitioned, apparently with some success despite the company’s initial skepticism, for re-employment (60). The main question at the time, then, was less the appearance of any prosthetic, but whether the person could perform specific tasks.

Medical writing about hand prostheses existed but was not of widespread lay interest in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Surgical manuals make clear why amputation might well be necessary as a treatment, and how best to sever bone from bone as needed. On the other hand, these were not particularly hopeful, forward-looking tomes, and they do not address aftercare beyond the initial wound and surgery. The influential Surgeon’s Mate (1617) described the implements of amputation as “very needful instruments to be at hand upon all occasions in the Surgeons Chest,” making clear how vulnerable the mariner’s body was, particularly if he—like a pirate—were at all likely to be shot at (2). Attempting to cure a gunshot wound was likely to lead to permanent aftereffects due to scarring, infection, and, often, amputation, with pain, inflammation, fever, gangrene, and mortification (what the buccaneers called “stiff limbs,” and compensated as they would an amputation); death, too, was far from improbable. Woodall’s Viaticum, Being the Path-Way to the Surgions Chest explained:

No wound of Gun-shott can be said to be a simple wound … [f]or the composition of Gun-shott-wounds are ever reall, and very substantiall, witnesse the poore patient, where Fibres, Nerues, Membrances, Veines, Arteries, et quid non, suffer together, so that such wounds in their recency resemble Vlcers rather then wounds … all the whole member suffereth together, and the parts adjacent in the highest degree. (5)

The reason for amputation might involve other possibilities—a badly broken bone due to accident or battle; uncontrollable infection in a limb; cancer. But violence was depicted as a leading cause.

Traumatically, it was sometimes alleged that the real reason for amputation was over-eager and under-skilled surgeons who amputated rather than attempting more complicated and labor-intensive forms of care; this was, of course, especially likely in a battle environment, or on a ship that might not even possess a qualified surgeon.16 The Pirate Captain William Phillips was wounded in the leg during battle. A General History of the Pyrates includes a harrowing description of the subsequent treatment: “There was no surgeon aboard, and therefore it was advis’d … that Phillips’s Leg should be cut off, but who should perform the Operation was the Dispute.” They pick the carpenter to do it, “Upon which, he fetch’d up the biggest Saw, and taking the Limb under his Arm, fell to Work, and separated it from the Body of the Patient, in as little Time as he could have cut a Deal Board in two; after this he heated his Ax red hot in the Fire, and cauteriz’d the Wound,” but did so clumsily, badly burning the man’s leg. Improbably, Phillips recovered—and later executed the carpenter-surgeon for an escape attempt.17 (Phillips’s colorful career ended in 1724, when yet another discontented carpenter led a successful mutiny against him.)

As with the historical Phillips, the fictional Long John Silver did not lose authority with his limb. He was arguably demoted from quartermaster to sea cook because of his disability, but this demotion lasted only until the pirates mutinied against Captain Smollett, whereupon he assumed command. And of course Lord Nelson, who was blinded in one eye and whose right arm was amputated above the elbow because of a musket wound, is the quintessential example of a man who lost an arm but not his status.18 While the loss of limb could theoretically befall a member of any level of society, though, it was certainly more likely to afflict men in the military and members of the laboring classes, who were more exposed to accidents and less likely to be able to dictate the terms of their treatment. Notably, enslaved Africans were particularly likely to be treated with amputation when other therapies might have been offered to white people in similar circumstances (Boster 45-48, 68-69).

Pirates, sensibly, if we are to take surgeons like Woodall at their word, expected to risk major injuries. Sailors often had to travel without good physicians or surgeons, and pirates were not any more likely than their cousins who sailed legally to have competent medical practitioners with them; they therefore had ample reason to plan for serious injury and the possibility of amputation—and they did, although their insurance payouts varied widely. According to A General History of the Pyrates, which as noted is often fanciful in the details but usually attached to some version of reality in the broad strokes, multiple crews had these kinds of provisions. Captain Bartholomew Roberts’ crew was promised that if “any Man should lose a Limb, or become a Cripple in their Service, he was to have 800 Dollars, out of the publick Stock, and for lesser Hurts, proportionably” (212).19 Captain Lowther offers a comparatively lower sum, for a pirate that “shall have the Misfortune to lose a Limb, in Time of Engagement, shall have the Sum of one hundred and fifty Pounds Sterling,” but, interestingly, such a man is also promised he may “remain with the Company as long as he shall think fit”—amputation need not amount to loss of employment; Lowther’s group appears to take a more generous stance than the East India Company had, when it needed much convincing to give work to the amputee Thomas Joyce (Defoe, General History 308). But whether the pirate’s continued employment implies prosthesis or any other manner of workplace accommodations is left unclear; no hooks of either silver or iron are invoked.

What is invoked, sometimes, is the value of a hand or other limb in terms of another human’s whole body. Pirates often attacked ships engaged in the transatlantic race chattel slave trade; while the effect of their engagement was occasionally to free enslaved African prisoners, they were not by any means a politically abolitionist group. Pirates calculated the worth of human prisoners, Black and white, based on their capacity to work at sea or their ability to be exchanged for money. Because pirates, like other mariners, were willing to consider captive humans a form of currency, they also entered into a calculus of human value. In this racialized metonymy, exchanges are predicated on both labor needs and identity, loss of limb equated mathematically to loss of freedom. In a well-known example of such exchanges, Henry Morgan’s group regarded the African and Indigenous captives of the Spaniards they were targeting as a fundamental part of their wealth and currency exchange system, so that the mutilation of a European’s body could be translated via a simple formula into so many non-European bondspeople. The Buccaneers of America chillingly records that among Morgan’s articles in the Panama campaign were promises that

for the loss of both Legs, they assigned 1500 pieces of Eight, or 15 Slaves, the Choice being left to the election of the Party. For the loss of both Hands, 1800 pieces of Eight, or 18 Slaves. For one Leg, whether the right or the left, 600 pieces of Eight, or 6 Slaves. For a Hand, as much as for a Leg. And for the loss of any Eye, 100 pieces of Eight, or one Slave. (Exquemelin 9)

Also noteworthy here is the severity of the injuries contemplated, and the apparent valuation whereby hands are worth more than legs, but individual eyes substantially less than either (the possibility of complete blindness is not explicitly addressed). But this shows, of course, only that the limbs might be lost and recompensed, not how the pirate might treat, or feel about, the impairment afterwards.

It is clear, though, that mariners expected to risk being maimed in their line of work, which if anything would make Captain Hook less remarkable, not more; and yet he remains a cultural standout. Further, Hook’s apparent prosperity also contrasts with the historical record of the sailors in what would have been his historical moment, had he really sailed, as Barrie wrote he did, with Blackbeard. Barrie joked that Hook was “the only man of whom Barbecue [Long John Silver] was afraid,” directly connecting him with a legacy of disabled literary pirates (Peter and Wendy 56). The pirates’ planning for disability pay described above outstrips what was available in the merchant service, in an example of what historians Rediker and Linebaugh have characterized as the radical egalitarianism that was characteristic of Golden Age piracy and set it apart from other maritime cultures.20

It also set them apart from land-based cultures, which offered no formal safety net for the poor or disabled. In a notable example, the collection of moral essays extraordinaire known as the Spectator in 1712 published an uncomfortable essay urging Mr. Spectator to “censure” the “scandalous appearance of poor” people in London by homing in on injured mariners as an example of the deserving poor who were failed by their society (166).21 This indifference was not universal, though, and some attempted to suggest policy solutions, including insurance conglomerates, or “friendly societies.” In 1745, John Griffin petitioned Parliament on behalf of sailors who were “Maimed, Aged, and Disabled” in the merchant service, arguing that since disabled naval seamen—the example he gives is “a poor Man, who loses his Limbe”—were entitled to pensions, merchant mariners ought to be as well (4).

Griffin wants something that will work as a complement to Greenwich Hospital, which was then a retirement home for mariners supported in part by automatic pay deductions. His petition notes that “by an Act made in the Eighth Year of the Reign of his late Majesty King George the First, For the more effectual suppressing of Piracy, every Seaman on board any Merchant Ship, who is maimed in Fight against any Pirate, is likewise to be admitted into the said Hospital”—but that the hospital lacks the resources actually to permit this (10). His argument, which is plagiarized in part from Daniel Defoe’s An Essay Upon Projects (1697), depends upon the threat of piracy throughout its reasoning; here (as in Defoe’s version), pirates are depicted less as losing hands than as taking them. A guaranteed pension in the case of disability at sea would save “many a good Ship, with many a rich Cargo,” he says. Here is why:

A Merchant Ship coming Home from Abroad, perhaps very rich, meets with a Privateer (not so strong but that she might fight him, and perhaps get off) the Captain calls up his Crew, tells them. Gentlemen, you see how ‘tis; I don’t question but we may clear ourselves of this Caper, if you will stand by me. One of the Crew, as willing to fight as the rest, and as far from being a Coward as the Captain, but endowed with a little more Wit than his Fellows, replies, Noble Captain, we are willing to fight, and don’t question but to beat him off; but here is the Case, If we are taken, we shall be set on Shore, then sent Home, lose perhaps our Cloaths, and a little Pay; but if we fight, and beat the Privateer, perhaps half a score of us may be wounded, and lose our Limbs, and then we and our Families are undone. If you will sign an Obligation to us, that we may not fight for the Ship and go a begging ourselves, we will bring off the Ship, or sink by her Side, otherwise I am not willing to fight for my Part. The Captain cannot do this; so they strike, and the Ship and Cargo is lost; which has often been the Case. (4-5)

It was often complained that merchant sailors hesitated to put up enthusiastic resistance in the face of pirate attacks, for why would a man risk life and limb for a company that was not likely to reward the sacrifice? Griffin’s use of this complaint stands out for just how strongly it emphasizes the risk to limbs over life in particular. Loss of limb meant “undoing.”

Defoe’s Essay upon Projects similarly complained that naval sailors received “Smart Money” (i.e., money for hurting) for disabling wounds while those in the merchant service did not. From 1721-4, threatened by a resurgence of piracy off the West African Coast, the Royal African Company (RAC) actually promised incentive pay—“Three Chests of silver”—to merchant crews who bravely resisted piracy (Minutes; Instructions).22 In addition, the RAC promised, “To every seaman that shall loose his Life in defence of the ship as aforesd thirty pounds, to be payd to his Widdow, Children, Father, Mother or Execrs &c” and “To every seaman that shall lose a Leg or an arm, For either Twenty pounds; for both thirty pounds, and for both legs, or both Arms, thirty pounds” (Royal African Company). One arm or one leg is therefore worth half as much as the entire man. But for the RAC, the incentive pay seems primary—mirroring the pirate or privateer’s pay for prey, they offer pay to avoid becoming prey—and the “smart money” seems secondary to their strategy. Griffin’s petition is strange not only for the way it focuses on lost limbs, but also for its timing. When Defoe wrote in 1697, or when the RAC developed its policies, piracy was a far more present and legitimate threat to trade than when Griffin recycled his rhetoric in 1745. Both authors use a connection between piracy and severed limbs to make a broader economic argument, but Griffin’s anachronistic use testifies to the extent to which pirate violence had already entered the realm of the powerfully figurative. Griffin, perhaps wanting to avoid any imputation of greed or privateerism, centers the fear of disabling injury. There also may be a calculation at work on the power of the idea of the injuring pirate, however figurative here, to fire the imagination.

Also worth considering is that Griffin says “limb” rather than specifying a particular injury, but leg amputations were considerably more common that arm amputations, and the loss of a leg is the more common symbol for nautical misfortune (Ott 14). While Griffin’s plan was to raise the funds for a hospital via subscription, Defoe suggested a payout scheme tagged very specifically to the limb that was lost (and, notably, significantly lower than what our piratical examples above were suggesting): £25 for an eye (£100 for both); £50 for a leg (£80 for both); £80 for the loss of the right hand but only £50 for the loss of the left, and so on (Essay Upon Projects 130). A widow would receive £50—the whole man evidently equivalent, for her purposes, to his right hand.

While lost hands could bear major symbolic significance, they simply do not dominate in the eighteenth-century iconography of disability. In both visual and textual imagery, wooden legs were far more common, often (but not always) functioning as stand-ins for poverty. They were associated with beggars, as in the Spectator—perhaps former war heroes, naval or army, who had sacrificed or been made to sacrifice on behalf of the homeland. They were also a subject for mirth and cruel humor. Simon Dickie writes that, “the man with a wooden leg becomes almost a master trope for testing the limitations of sympathy,” and after all, “many deformities were predictable consequence of labor” (93).23 Responding to scholarship like Dickie’s, Gabbard and Mintz wonder why the “great age of sensibility” is better known for its derision or hostility than compassion for people with physical impairments and disabilities; their answer, in part, is because sensibility functioned on amelioratist logic, demonstrating the moral virtue of a select few of the able-bodied by allowing them to demonstrate their pity and sympathy (10-13). Sensibility itself was understood as a highly physical matter, arising from the body’s material nerves and their vibrations as much as from the metaphorical heart. Missing limbs, so often the revenants of war wounds or workplace injuries, could potentially testify to a person’s virtue or innate dignity, but this was far from a universal interpretation, and the ableist correlation between moral and physical deformity was an ever-available trope. For all these reasons, the oddly limbed pirate would seem to make perfect sense—and yet there is little evidence of such figures in imaginative works prior to the nineteenth century, and none at all of hook-wearing ones.

II. Disability and the prosthetic hand

This section considers the history of hand prosthetics in more detail, and attempts to offer some context for understanding the hook-using pirate figure in terms of disability. The course of the eighteenth century saw the gradual emergence of disability as a generalized category, as opposed to singular instances of injury or inability, as well as an emerging consensus that disability often could and should be treated medically.24 My emphasis here is on prosthetic hands, which have a long history, but one that refuses to come into focus as sharply as the more ubiquitous artificial leg. Before the industrial accidents of the later eighteenth and nineteenth centuries became a common source of manual loss, warfare and dangerous nautical labor were the primary reasons a person, most often a man, might lose a hand or arm; at least a sporadic interest in functional replacements for these losses seems to have developed early as well.25 John Gagné, for one, has shown that plans for prosthetic hands (and arms) stretch back at least to the 1400s, and moreover were, if hardly omnipresent, at least “eminently feasible” as treatment for amputation (134). Per Gagné, prostheses were usually made by artisans and tradespeople—blacksmiths, carpenters, leatherworkers—which may have made them more accessible down the social ranks than is commonly thought. And indeed, as late as the nineteenth century, as Sue Zemka has shown, artificial limbs were often still “designed and made by artisans, men who … took a craftsman’s approach to the problem.”

Despite the fact that hooks would have been simple and easy to construct from shipboard materials, not to mention just generally more usable than hand-like prostheses, there was considerable interest in the early modern period and eighteenth century in making artificial limbs lifelike and movable, a challenge considerably more daunting in the case of the iron hand than the wooden foot. David Turner cites a 1749 London advertisement in The Scots Magazine for a French surgeon who both amputates all manner of body parts, and sells “wholesale of retale [sic] all sorts of legs, arms, eyes, noses, or teeth, made in the genteelest manner” after the fashion of “persons of rank in France” (qtd. in “Disability and Prosthetics” 301). Ambroise Paré’s (1510-90) account of ingenious clockwork hands made by a locksmith that could bend their fingers is perhaps the best-known example from the early modern period, but it is not isolated. Incidentally, and evocative of Captain Hook, Paré did not write about hooks for hands, but he did write an account of hunting for crocodiles in the River Nile by using strong metal hooks baited with meat (680).26 On the other hand, clockwork hands and lifelike legs with flexible knees or ankles do not appear to have been widely adopted in the early modern period, or at least are not represented that way. Common people, based on what we see in periodicals and engravings, were more likely to use a wooden peg leg. And while images and descriptions of wooden legs abound, there is little proof that the average sailor used any prosthetic hand at all. Surviving hand prostheses, artisanal creations of metal and leather, tend to be hand-shaped, and often to have movable fingers, even when the purpose of such hands was not primarily aesthetic, but instead to restore function to the warrior or tradesman who needed still to work.27 This is a detail that the often fanciful David Jenkins’ Our Flag Means Death (HBO 2022) gets right: the pirate-adjacent character Spanish Jackie (Leslie Jones) sports a jointed, realistic wooden hand that she can use to smoke.

Many who could manage it seem largely to have avoided the inconvenience, and likely the discomfort, of hand prostheses entirely, or at least this is how things are portrayed. The leftwards messenger in the 1790 etching “An Admiral’s Porter” wears an eyepatch and has his missing hand discretely tucked into his chest with the help of a sling, while his companion uses a crutch rather than a peg; the lack of artificial limbs may show their penury, but also it corresponds to their obvious mobility and ability to perform useful work. [Figure 3] Higher up the status ladder, there is no record of the historical Admiral Horatio Nelson using a prosthetic, although Moby Dick’s fictional Captain Boomer, who may well have helped inspire Barrie, has an odd, self-fashioned, mallet-betopped extremity.28 When Jane Eyre’s (1848) Rochester has his left hand amputated, we are told only that, “the left arm, the mutilated one, he kept hidden in his bosom”—there is no suggestion that he uses an assistive technology (… expect perhaps his marriage). While some women did need and use prosthetic limbs, depictions of amputees tend to focus on men, wrapping up the idea of patriotic sacrifice with the masculine body.29 In an unusual example of female amputation, Catherine Maria Sedgwick’s historical romance Hope Leslie (1827), the Pequod woman Magawisca tragically loses her arm fairly early in the narrative; thereafter she usually wears a discrete cloak, but is never depicted using a prosthesis.

Figure 3. [Two disabled veteran sailors, employed by an admiral as messengers, delivering a letter to the servant at the front door of a town-house. Coloured etching after G.M. Woodward, 1790. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).]

One status-conscious amputee of the early nineteenth century, Captain George Derenzy, offered a helpful tip strongly suggesting that prostheses were not at all the rule: “To those who have lost the whole arm it will be found very useful to have a loop of black ribbon fastened into the inside of the coat sleeve near the shoulder on the defective side, and of sufficient length to allow of its being fastened to a button of the waistcoat; by which means the coat will be prevented from falling off at the shoulder.”30 Derenzy’s work notably prioritizes almost every technology he can imagine except the hand or arm prosthesis. His fascinating Enchiridion: Or a Hand for the One-Handed (1822) describes the Captain’s own designs, not for a hook hand or other prosthesis, but instead for a series of devices to make everyday activities easier to do with a single remaining hand, such as nail-filing and eating one’s breakfast egg.31 The devices are, significantly, designed to look tidy and to be easy to carry and use, and to promote the user’s comfort, self-care, and independence. My favorite among the list is a rather superior looking spork: a curved utensil that combines the tines of a fork with the blade of a cheese knife for ease of cutting and eating one’s meals. It comes with a stylish carrying case of red Moroccan leather, which is spring-loaded so that it may be opened easily with one hand.32 (The item is an elegant predecessor of the “Nelson fork,” a knife-fork combination popularized after the army presented one to Admiral Nelson.) Derenzy’s assistive technologies, then, were meant to maintain a level of social status by enabling physical function consistent with that status.33 While a hook might enable a soldier to steady a rifle, or a heavy armored glove prosthetic to grasp a horse’s reins, for some men the important issue was to be able to sit with dignity at table, or to hold a pen.

Captain Hook, markedly, would not be among that group; his prosthetic inventions were a double-cigar holder and a murderously sharpened hook. The case of a man named James Cragie, which was detailed in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1793, stands, like Derenzy’s aspirational devices, in strong contrast to the extremely violent uses to which Hook puts his own inventions. The “Character of Gavin Wilson,” essentially an advertisement, describes its subject as an “ingenious artist,” that is, a journeyman bootmaker of Edinburgh who had a sideline in cleverly constructed prosthetic limbs. It includes a letter, reprinted from the Caledonian Mercury, in praise of Wilson’s wares, purportedly from James Cragie, “a person who was unfortunate enough to be deprived of both his hands [they were taken off by an 18-pound cannon ball near Ticonderoga] while serving in the Royal Navy,” but who is now able to write and perform offices of self-care thanks to his leather hands (308-309). Cragie had been pensioned, but said that he still felt he had been “rendered useless to my king, my country, and myself,” until fitted with his leather prostheses (309). The wrists and fingers of his new hands could be bent, thanks to hollow “balls and sockets made of hammered plate brass,” and a screw plate in the palm allowed them to hold knives and forks. Two of the details here stand out: the description of Cragie’s inability to write, restored with hand-like prostheses, is couched in the language of patriotism and national identity: to feel himself British, he must work. But the need to employ a complex, jointed artificial hand, to which utensils are affixed, rather than a simple measure like attaching a hook or other tool directly to his wrist, is not questioned: it is better to have either no hand, or a lifelike hand, than an in-between utilitarian solution.

In a literary example of this principle, Charles Dickens’ Dombey & Son (1846-8) offers us Captain Cuttle, a rumored privateersman with a hook for a right hand. [Figure 4] Cuttle, who “unscrewed his hook at dinner-time, and screwed a knife into its wooden socket instead,” is a kind-hearted and loyal soul, but also decidedly uncouth, often gesticulating and even kissing his hook as though it were a right hand of flesh in a manner the narrator finds mildly off-putting. The utilitarian hook registers as bad, or at a minimum strikingly unpolished, manners.

Figure 4. [Frontispiece to Dombey and Son, by Charles Dickens, with illustrations by H. K. Browne (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848). Beinecke Library.]

The non-medical interest in bodily disability was strong and often contradictory, torn between interest and pity. In their foundational study of disability in the long eighteenth century, Helen Deutsch and Felicity Nussbaum argue that “in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a ‘defect’ was both a cultural trope and a material condition that indelibly affected people’s lives” (1-2). Prosthetic devices centered around walking are arguably more ambiguous, or perhaps multipurpose, than arm prostheses. The cane or walking stick (or for a lady perhaps a parasol), for example, could indicate fashion or wealth, or be used as a means of self-defense, as well as serving as a mobility aid (Bourrier 49). Even as the technological possibilities for light and useful prosthetic legs increased over time, the cheap and reliable peg leg remained commonly visible (Bourrier 51). Moveable metal prostheses in the eighteenth century and earlier could be noisy. According to Stephen Mihm, “amputees often carried an oil can with them”—another reason to prefer a peg or crutch (284). Walking aids are generally not treated as incongruous or arresting, not compared to the jarring sight of a hook for a hand in literary and visual representations.

The language in Cragie’s testimonial, then, points to a developing difference between the early modern and eighteenth-century understanding of impairment, and that of the nineteenth century. Over time, the appearance of the prosthetic came to matter more and more; its function was to restore image and symmetry as well as movement. In the eighteenth century, argues David Turner, the medical community saw an amputee as possessed of a “deformed” body, and “a deformed body was necessarily an unhealthy one” (Turner, “Disability and Prosthetics,” 303). Because of a pervasive eighteenth-century culture of exercise, anyone whose impairments made exercise difficult “were thus seen as naturally unhealthy,” and so restoring movement and encouraging muscle use were key medical tenets, which explains both the utilitarian concern with prostheses that we have seen, and perhaps also the relative lack of interest in hand prostheses versus legs—and the preference for realistic, less functional hand prosthetics versus functional hooks in the cases where an artificial hand was preferred to a sleeve discretely tucked into a pocket or bosom (Turner, “Mobility Impairment” 43).34 During the period most associated with piracy (the so-called Golden Age), there seems to be almost no discourse around hook-handed men or mariners, and so we must look further forward for the origins of that image. In the nineteenth century, visible disability was more explicitly depicted as incompatible with bourgeoise propriety and higher social status. The action that Hook takes, to make his disability both his calling card and a useful weapon, is almost comically defiant to this mode of propriety.

III. Captain Hook

It seems eminently likely that rather than Hook’s hook being inspired by the historical pirates of the Caribbean, the common belief in hook-handed pirates was inspired by Hook. While no pirate historian to date has published evidence of the widespread use of a hook prosthetics among pirates, the possibility is at least plausible. While amputated arms were less common than legs, these were far from unheard of in sea life. For example, the pirate and Madagascar enslaver Captain Condent/Condon, was missing one hand (or arm, depending on the source), but there are no known references to his having used a hook prosthetic.35 The question is less the missing limb, then, but whether pirates used particular prosthetic limbs to replace them. By the mid-nineteenth century, it was true that the artificial arm ending in a hook was a cheap and practical possibility for a soldier whose arm had been lost to war (Kirkup, 160-161). But whether hooks—as opposed to either more handlike prosthetics, or simply a stump tucked into a shirt or sleeve—were very common earlier on is unclear at best. As there are no widely known depictions of Golden Age pirates using hooks in either history or fiction, it seems unlikely that the origin of the common belief in such figures comes to us from the archives, instead of from Barrie.

First appearing in J. M. Barrie’s 1904 play, Peter Pan, Hook was famously a late addition during the composition of the drama, which had not originally featured a clearly demarcated villain at all. Barrie’s novelization of Peter Pan, the 1911 Peter and Wendy, describes him pointedly as regal, cowardly, and beclawed:

A man of indomitable courage, it was said of him that the only thing he shied at was the sight of his own blood, which was thick and of an unusual colour. In dress he somewhat aped the attire associated with the name of Charles II, having heard it said in some earlier period of his career that he bore a strange resemblance to the ill-fated Stuarts; and in his mouth he had a holder of his own contrivance which enabled him to smoke two cigars at once. But undoubtedly the grimmest part of him was his iron claw. (67)36

In other words, Hook’s hook is a major and material part of his character, flagged from the start as iconic, and in provocative contrast with his vaguely regal bearing. Barrie’s ableist conflation between Hook’s evil and his disability was a common shorthand within the context of the Victorian stage, although the banality of this prejudiced trope makes it no more acceptable than his unbearably racist depictions of Native characters elsewhere in the play, though these, too, were common in contemporary representations. Even so, Hook has not primarily been read through the lens of disability studies; instead, we have an enduring tug-of-war between symbolic and historicist interpretations.37 Many readings of Hook and the hook have been proposed—perhaps most often variations on the Oedipal theme, wherein the hook is a prominent but ultimately failed phallus—but there is also considerable investment in trying to identify potential literary-historical antecedents for the character (besides Charles II, whom Barrie himself invokes). None of the proposed pirate ancestors, though, offers obvious or indelible proof of a pirate with a hook prosthetic.

Historical figures who have been proposed as Hook’s inspirations include James Cook, the “pirate” called “Barbarossa,” Christopher Newport, and even the terrestrial soldier Henri de Tonti.38 The first two we may dispense with quickly. Captain Cook, a famous explorer, was in full possession of both of his hands up until the day he was dismembered in 1779, although undeniably he was a famous mariner, and the names do rhyme. Oruç Reïs was a famous corsair of the western Mediterranean whom the Europeans called Barbarossa; a story told of him was that in 1512 he lost an arm to the Spanish, and thereafter wore a silver cap or prosthetic—but no mention is ever made of him using a hook.

Newport is a more tempting potential referent. The Elizabethan privateer and Virginian colonist apparently lost an arm in battle: as captain of the Little John in 1590, his “right arm [was] strooken off” near Cuba while he was (unsuccessfully) trying to take a pair of Spanish galleons from Mexico (White 321). Newport is sometimes depicted as having replaced his arm with a hook—so much so that when a statue was unveiled of him at Christopher Newport University depicting the captain with both arms, it provoked a minor scandal (Dougherty). Moreover, the one thing we can be sure about with respect to Newport is that he continued actively privateering for most of twenty years; he was another of our rare one-armed active captains. More tantalizing still, in 1605, Newport gifted a live pair of crocodiles from Hispaniola to King James (Ransome). Hook, Captain, and crocodile are all here united tidily in a single historical figure, even if he did serve the wrong Stuart for Barrie’s Charles II-favoring creation. However, there seems to be no contemporary source verifying that choice of prosthesis for Newport; indeed, our only contemporary witness to his loss of limb, John White, doesn’t mention how much of the arm he lost or whether he used any prosthetic technology at all. I have not been able to find any source suggesting Newport wore a silver hook that predates Barrie’s play. Likely, then, the assumption that Newport wore a hook follows from Captain Hook, rather than Hook’s hook from him.

The belief in Newport’s hook may also be linked to another possible Hook inspiration, Henri de Tonti. Tonti was a French military officer native to Sicily, and, like Newport, a North American colonialist. In 1674, fighting in the Messina Revolt, he lost his right hand to an explosion. Thereafter he seems to have worn a metal prosthesis covered by a glove. His portrait by Nicolaes Maes is a rare example of a seventeenth-century man shown wearing a prosthetic limb—in a hand shape, or perhaps it is hook-like; it is unclear. [Figure 539 It was more common for portraits to idealize their subjects than to immortalize scars or impairments; Maes seems to split the difference. There was, provokingly, some avid interest in de Tonti around the time of Peter Pan’s composition. A 1903 romance by William R. A. Wilson, A Rose of Normandy prominently featured an iron-handed Tonti hectoring Native North Americans, but he is actually the dreamy heroic lead, rather than a villain. Edward Sims van Zile’s With Sword and Crucifix includes a proud and satirical de Tonti, much more Byronic in character, but his iron hand is not referenced the way it is in the other fiction. In other words, de Tonti is one among several adventurers whose parallels to Hook include one-handedness—one who was even prominent in contemporary popular fiction—but who was not, in the end, clearly associated with the use of a hook prosthetic.

| Figure 5. [Nicolaes Maes, Henri de Tonti, History Museum of Mobile. Image file on Wikimedia Commons.] |

What reasons besides history may Barrie have had for assigning his villain a severed hand and iron claw? (What, in other words, made the story’s hook such a hook?) The material prosthesis works as a metaphor, well enough that it need not even require the hook to have been real at all, although I believe readers tend to want it to have been. If historically severed legs were more common than dismembered hands, still there are metaphorical reasons Barrie might have preferred the latter, and not only because when it came to missing legs, Stevenson had beaten him to the punch. At the risk of belaboring the obvious, the hand has a particular freight in nautical parlance, as the hand is so strongly synecdochal for the man that we have accepted the expression “all hands on deck” as a matter of course since at least the early eighteenth century. In 1719, Robinson Crusoe, musing upon his lack of labor partners to fit out a vessel, remarked pointedly, “If I had had hands to have refitted her, and to have launched her into the water, the boat would have done well enough,” later wondering whether he could make a canoe, “even without tools, or, as I might say, without hands” (149).40 Hand, man, and tool are inseparable within the linguistic hydrarchy; it is no great stretch to literalize this just a little bit further in the figure of Hook.

Hook’s particular realm of villainy—piracy—makes this metaphorical melding especially likely. From around 1820 or so, and at least for the next several decades, “thieving hooks” was a synonym for fingers (“hooks,” as short for “thieving hooks,” could also mean fingers), and “thieving hook,” in the singular, for hand. For example, a lurid 1838 magazine pirate yarn offers this phrasing to the lucky reader: “he claps his thieving hook upon my shoulder in going aloft, and shoves me under” (“Pirate Craft” 888). “Hook” could be a euphemism for a pickpocket as well, presumably synecdochcally for the use of those same thieving fingers. Moreover—and I suggest this context as complementary, not as an alternative to the metaphor just discussed—the theatrical and later the film medium in which Captain Hook was developed as a character is significant. Not coincidentally, nineteenth-century melodrama was markedly friendly to pirate tales (Burwick and Powell 33-57). Melodrama deployed a stylistic system in which its characters’ “moral states [could] be seen in their bodies and heard in the tenor of their words,” using physical expression to provoke physical emotion: emotion and morality both by the body and of the body (Holmes 16-17). Melodrama was thus unsurprisingly prone to use “physical monstrosity,” a la Richard III, as a cue for delineating the villain; early film picked up that tradition as well (Mitchell and Snyder 97).41 Furthermore, from a costuming point of view, a missing hand or hook prosthetic is far easier and probably more comfortable to depict than a missing leg.42 The particularly Victorian flavor of conflating physical disability with moral monstrosity can be seen in the total physical contrast between Hook—older, suffering, marked—with Pan, a symbol of youth and vitality who eerily flashes his perfect white baby teeth when he smiles.

Besides, to locate monstrosity or alienation in the hand was arguably a strongly Victorian choice. In her study of severed and disembodied hands, Katherine Rowe argues that in the Western tradition, “the hand is the preeminent bodily metaphor for human action,” Aristotle’s instrument of instruments–that is, “manual activity” is symbolically linked to human agency (x, xii).43 See, for example, the importance of manual gesture to acting, particularly on the pantomime and melodramatic stages. Rowe also argues that the Gothic writing of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries pays unusual attention to disembodied hands, including Hand of Glory stories (about the special powers of the hands of executed criminals), which became popular a century and more earlier (112, 120).44 There is, following Rowe, a strong line between the severed hand and the uncanny, one that resonated strongly in the cultural moment of Peter Pan’s composition. And so, there are a great many reasons, cultural, aesthetic, and linguistic, that might have suggested to Barrie his villain’s memorable prosthetic.

I do not engage in this manual digression to discount the material possibility out of hand (if you will). It is very likely that Barrie had encountered men using hooks in his own lifetime, and, as we do today, simply extrapolated backwards: such things are, and so such things may have been. The earliest surviving metal hand prostheses seem to date from around 1450; their number has only increased since that point, although these very old prostheses are not hooks, but instead hand-shaped.45 (Perhaps hooks were less used, or perhaps they were less likely to be preserved; perhaps both; we don’t know.) By the middle of the nineteenth century, particularly after the American Civil War (as well as the Crimean War, for British populations), the use and variety of prostheses available to the public had expanded considerably compared to the previous centuries (Turner, “Disability and Prosthetics” 301). This is because they were needed. While musket balls always had the potential to cause catastrophic injury to human limbs, the firearms used in the Civil War, deploying hollow “Minié balls,” were particularly likely to destroy bones upon impact, and created messy, dangerous wounds; overburdened field doctors practiced amputation widely. Thanks in part to the nascent but increasing use of antisepsis, their patients were more prone to survive than previously (Mihm 282-3). Moreover, Michals argues that in the eighteenth century, naval amputees may have been more likely to live through and recover from the operation than similarly afflicted civilians (Michals, “Lame Captains” 16-17). All of this together added up to an explosion in the number and variety of prosthetic limbs manufactured and worn by both Americans and Europeans; hooks were just one among several options, but were among the cheapest and most utilitarian.

But this fact points us to something curiously out of place about Hook’s iron claw, if we wish to consider it a nod to Barrie’s own moment rather than to the Golden Age of Piracy. By the last third of the nineteenth century, prosthetic limbs, once heavy concoctions of wood, metal, and bone, but now composed of lighter materials and able to make use of innovations such as vulcanized rubber, could look and move more like organic body parts than in earlier times. In a brutal irony, the rubber extraction forced upon Congolese people that enabled advances in European’s artificial limbs was infamously associated with the severed hands of people murdered in the pursuit of rubber quotas.46 It is provocative, then, that Barrie reached for a simple hook prosthetic in imagining his iconic pirate. Conceivably, the difference between the hook and the more genteel prosthetic hands that would have been available to Barrie’s contemporaries (or, in contrast, the precious and beguiling silver arm said to have been used by the corsair of legend, Barbarossa) has less to do with history than an issue with decorum.

The fin de siècle was, overall, more obsessed with seeking a link between the body’s outward appearance and inward morals than many previous cultural moments had been, and was less forgiving of amputees in the middle classes and above who did not try to hide their impairments politely from the public gaze (Mihm 288-289). As Ryan Sweet argues, there was a powerful “social preference for physical wholeness: a predilection culminating from several factors, including the rise of bodily statistics, the vogue for physiognomy, and changing models of work,” so that the loss of a limb, or an eye, or even hair or teeth were stigmatized similarly (Prosthetic Body Parts 4). To choose function over form in that prosthetic is to misalign an important aspect of Hook’s appearance with his aristocratic aura, at least by nineteenth-century standards, and quite probably by earlier ones as well. Hook is a careful dresser with aristocratic taste, but he is unquestionably open about who he is, and the hook, however deplorably, marks him as a villain even more emphatically for Barrie’s first audiences than for ours.

This brings us back to the question: following the “thieving hook” resonance, was Hook’s hook only ever a stage metaphor? Had he no human forbearers at all?

Not among real pirates, no. Hook can at least in part be understood as a literary composite, owing something to Robert Louis Stevenson’s one-legged but nimble and magnetic Long John Silver, even as he stands simultaneously as the temperamental opposite to Dickens’ kindly Captain Cuttle. Another possibility, discussed above, might be that he was inspired by the foil to Melville’s peglegged Ahab, Captain Boomer of the Samuel Enderby. Both Rowe and Peter Boxall posit that there is a marked increase during the nineteenth century in fictions of the “dead hand”—hands that are really or metaphorically disembodied, cut off from the material wholeness of the body. Boomer’s example is, then, an apropos part of this pattern. His arm had been amputated after being wounded in an encounter with the White Whale, and, when Ahab encounters him, he boasts, “a white arm of sperm whale bone, terminating in a wooden head like a mallet”—an interesting implement designed by himself, and whose purpose is unclear.47 (While the ship’s surgeon claims he uses it to bash in his colleagues’ heads, this is clearly said in jest.) But if the prosthetics in Moby Dick are “the coming together of the living hand with the dead, of the living limb with the whalebone aesthetic,” as Boxall would have it, then Hook’s prosthetic is, like the ship flying a jolly roger, the coming together of the living and death itself (Boxall 18). Small wonder, then, that we often look to dead men in search of whatever germinated him.

The recurrent postwar increases in the use of real hook prostheses after the U.S. Civil War, and again post WW I, must have helped to amplify the sea change in hook iconography marked by Captain Hook, but this is not a complete explanation of Hook’s influence. Hooks were not popular in visual media and visual culture until after Captain Hook, and the hook he brandishes is a solution to a missing hand, but also a solution that conveys that he is a villain, and moreover a villain in the realm of children’s literature; the imaginative leap from disabled mariner to Disney fodder is massive.

It is possible that Hook’s hook—and the hook-wearing pirate in general—has a basis in historical reality, but that possibility is not well supported by the historical record. Turning to the historicist possibility prior to the culturally informed theoretical ones is an easy answer that downplays the role of fiction and stage—the literary—in creating common knowledge. It also downplays the ableism of writing that thrills in the association between prosthesis and evil. The modern image of the pirate would seem to lend itself naturally to a disability studies lens—often more prosthetic than organic, the pirate in popular culture is frequently missing at least one hand, one eye, and often at least one leg as well. Straining credulity (see LEGO’s Metal Beard the Pirate, who is merely a head atop a fantastical prosthetic creation, for an extreme example), the prosthetic possibilities have become half the imaginative fun, an end in and of themselves. But a disabilities approach to understanding pirates and their limbs is not common; instead, a loose historicism offers to explain the pirate prosthesis as realistic, and too often, it stops there. Hook’s hook suggests one angle for understanding the relationship between piracy and disability, piracy and prosthesis. It is also a powerful example of how what feels familiar can be mistaken for what feels true.

Notes

1 See for example Erll and Nünning; Assmann and Shortt; and Ben-Amos and Weissberg.

2 “A strong sense of general familiarity, together with an absence of specific recollections, adds up to a lethal recipe for misattribution” (Schacter, Seven Sins 97). See also Schacter, “Adaptive Constructive Processes.”

3 The Mandela effect is the phenomenon whereby people share specific false memories about major cultural phenomena: e.g., that Nelson Mandela died in prison. The phenomenon was named by Fiona Broome, a paranormal researcher, in “Nelson Mandela Died in Prison? The Mandela Effect” in a blog post in 2010, and is sometimes taken as proof of alternate universes, rather as déjà vu is taken by some as evidence for past lives. On the other hand, psychologists are far more likely to suggest the Mandela effect is evidence of the constructive nature of memory.

4 As Prasad and Bainbridge explain, “a proportion of what dictates memory performance is intrinsic to the stimulus and independent of individual experience” (1972).

5 The General History of the Pyrates was attributed to Defoe in John Robert Moore’s Defoe in the Pillory and Other Studies (1939); that attribution is rejected by Furbank and Owens’s The Canonization of Daniel Defoe (1988) and Defoe De-Attributions (1994), as well as by the present author. Although some substitute authorial candidates have been suggested—in particular, Nathaniel Mist—no definitive identity for the text’s author has yet been established.

6 For further discussion of jokes about “healing” wooden legs, which was apparently a long-running phenomenon, see Van Horn 381.

7 On this point see Sweet 88-89.

8 Talia Schaffer has argued that a Victorian heroine might understand a lover’s disability as a way to form a judgment of his social character before agreeing to partner with and help care for him (160-61). Are we, though, to imagine such a virtuous relationship between Long John Silver and his unnamed Black wife and confidant?

9 Stevenson was also, interestingly, sent to try the effects of cold mountain air as well as warm sea breezes.

10 The origin of the claim that Read passed as a man on board ship, which is contradicted by court testimony in her trial, can be found in The General History of the Pyrates, and is credulously repeated by dozens of subsequent accounts. The “Mark Read” pseudonym originates in John Carlova’s 1964 novel, Mistress of the Seas. On the curious permeation of known fictions into modern historical scholarship on Mary Read and Anne Bonny, see Rennie 265-9. The Cherry Tree Myth was the invention of one of Washington’s first biographers, Mason Locke Weems.

11 On pirate welfare, see also Rediker, Villains of All Nations 73-74; Rediker, Outlaws of the Atlantic 69-70; and Leeson, Invisible Hook 71-74.

12 Sweet’s chapter is particularly useful as one of the only extended readings to treat pirate prostheses as narrative prostheses.

13 On Barrie’s literary influences, see also Friedman, Second Star; Stirling; and Green.

14 Both locations are erroneously attached to stories about Captain Kidd’s treasure, as are numerous other islands and enclaves.

15Unfortunately, pensions were underfunded and not always easy to secure. Chronic wounds or ulcers that would not heal, for example, were not usually enough to secure a man a pension; amputation, providing its cause was documented, might be (Nielsenm196).

16 Turner, “Disability and Prosthetics” 305.

17 Defoe, A General History 344-5.

18 Teresa Michals shows that in effect, Nelson (and officers who follow his example) is the exception that proves the rule: while “amputation was widely represented in the eighteenth century, Nelson’s portraits are unusual” because they unabashedly pair amputation with admirable military masculinity. “Invisible Amputation” 17; see also Lame Captains 128.

19 Note that “dollar” here is a reference to the Spanish dollar, aka a “piece of eight,” minted at about one ounce of silver per coin. This made them theoretically equal to a British pound sterling, except that the exchange rate in Britain artificially favored their own currency, which partly explains the difference between Morgan’s and Lowther’s rates.

20 Linebaugh and Rediker argue that the maritime world is organized “from below” by sailors in “motley crews”—and that pirates go a great deal farther in terms of organized resistance than other mariners (Many-Headed Hydra 156-67).

21 The gist of the essay (number 430) is a request that Mr. Spectator instruct the public on how to tell true beggars from undeserving ones, largely by distinguishing those who are physically impaired from those who sham impairment to generate sympathy. The fear of being taken in by the beggar who falsified their impairments was a perpetual bugbear of the middling classes well through the nineteenth century as well.

22 My profound gratitude to David Wilson for directing me to the RAC Minutes cited here and below, and for sharing his transcriptions. For context on the RAC’s position, see Wilson, Suppressing Piracy 161-2.

23 Ross Carroll makes the point that at least some social philosophers—Shaftesbury and James Beattie are named—regarded laughing at physical disability as appalling (28, 143).

24 C.f. Turner, Disability in Eighteenth-Century England 3-5.

25 There were two main causes for the normalization of seeing male amputees in the latter portion of the nineteenth century: industrialization, which caused industrial work accidents, and war, particularly the U.S. Civil War, meant that more male laborers than ever were losing limbs (Bourrier 44).

26 Benerson Little has proposed a similar crocodile-hunting scene from Exquemelin’s Buccaneers of America as a likely inspiration for Barrie’s Captain Hook, but the combination of crocodile with extensive descriptions of artificial limbs in Paré’s oeuvre is suggestive, even if only a coincidence.

27 Indeed, following Turner and Withey, it was not until well into the eighteenth century that using medical technologies only to improve the body’s aesthetics came to be seen more commonly as a virtue rather than treated with suspicion (“Technologies of the Body” 780).

28 Nelson is sometimes depicted with a hook—James Gilray’s 1798 “Extirpation of the Plagues of Eqypt” is a well-known example—but such examples are better understood as caricature than realism. See Michals, “Invisible Amputation” 24-25.

29 Turner argues that prosthetics are a deeply gendered issue in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (at least potentially positive for men; never so for women); Gagné that they were a strongly masculine matter in the early modern period.

30 Derenzy, Enchiridion 53.

31 For an extended discussion of the Enchiridion and its authors status and masculinity, see Daen 93-113.

32 This was one of the dearest implements in Derenzy’s catalog, retailing for 1 pound 1 shilling. The case was 4 shillings extra.

33 On Derenzy and class/gender, see also Daen 105-106.

34 As Teresa Michals notes, the hand tucked into a waistcoat (think of Napoleon) was a common pose for genteel masculine portraiture regardless of handedness, and so can function as a way to elide the visibility of amputation even when it’s being shown (“Invisible Amputation” 31).

35 His first name is often given as Christopher, but there are many variants, including Edward. Baylus Brooks puzzles over how the first name “Christopher” became attached to this man at all, since it occurs in none of his eighteenth-century sources (192-94). Possibly there was some twentieth-century confusion between the one-armed Christopher Newport and the one-handed Congdon.

36 I have incorporated the prose description of Hook, as it may be more familiar to the reader, but the original stage direction uses very similar language: “Cruelest jewel in that dark setting is HOOK himself, cadaverous and blackavised, his hair dressed in long curls which look like black candles about to melt, his eyes blue as the forget-me-not and of a profound insensibility, save when he claws, at which time a red spot appears in them. He has an iron hook instead of a right hand, and it is with this he claws. […] A man of indomitable courage, the only thing at which he flinches is the sight of his own blood, which is thick and of an unusual colour. At his public school they said of him that he ‘bled yellow.’ In dress he apes the dandiacal associated with Charles II., having heard it said in an earlier period of his career that he bore a strange resemblance to the ill-fated Stuarts. A holder of his own contrivance is in his mouth enabling him to smoke two cigars at once. Those, however, who have seen him in the flesh, which is an inadequate term for his earthly tenement, agree that the grimmest part of him is his iron claw” (Barrie, Plays 40).

37 Ryan Sweet is an exception here; see also note 10. Hook is often cited, glancingly, as a well-known example of disability in film or in children’s literature, but interpretive readings of Peter Pan concerned with Hook have not traditionally unpacked him as an example of negative portrayal of disability. See, for example, Margolis and Shapiro 18-22; Dowker; or Rubin and Watson 60-67.

38 See, for example, Lester D. Friedman, “Hooked on Pan” 193-4; and Alfonso Muñoz Corcuera, “True Identity” 70-74.

39 This image was in private collection until the 1930s; Barrie probably could not have seen it.

40 On Crusoe, see also Boxall 86-99.

41 Mitchell and Snyder specifically name Captain Hook as an example of the character type they call a “disabled avenger” (99).

42 The theatrical adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Dombey and Son (1846-48), entitled Dombey and Son, or, Good Mrs. Brown, the Child Stealer, depicted Captain Cuttle with a hook prosthesis, at least according to the illustrations in Penny Pictorial Play no. 4.

43 See also the Introduction to Peter Capuano and Sue Zemka’s Victorian Hands.

44 On “the hand of death, see also Stainthorp 11-13.

45 “From the century or so between 1450 and 1600 about thirty iron hands/arms survive, almost equally balanced between right and left” (Gagné 142). These were not, according to Gagné, relegated to the chivalric class, but were available to craftspeople and artisans, too (the labor pool who would have had the skills to make them) (143).

46 On hands, race, and rubber extraction, see Briefel 129-150.

47 David Park Williams, although he is more attached to a comparison between Hook and Ahab, still puzzlingly suggests that “from mallet to claw hammer to iron claw is no great stretch of the imagination” (486).

Works Cited

Addison, Joseph and Richard Steele. The Spectator. Volume 6, edited by George Aitken, London, 1898.

Assmann, Aleida and Linda Shortt, editors. Memory and Political Change. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Barrie, J. M. Peter and Wendy. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1918.

—. The Plays of J. M. Barrie. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1928.

Ben-Amos, Dan and Liliane Weissberg, editors. Cultural Memory and the Construction of Identity. Wayne State University Press, 1999.

Bilguer, Johan Ulrich. A Dissertation on the Inutility of the Amputation of Limbs. London, R. Baldwin, 1764.

Boster, Dea H. African American Slaver and Disability: Bodies, Property, and Power in the Antebellum South, 1800-1860. Routledge, 2013.

Bourrier, Karen. “Mobility Impairment: From the Bath Chair to the Wheelchair.” A Cultural History of Disability in the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Joyce L. Huff and Martha Stoddard Holmes, Bloomsbury, 2020, pp. 43-60.

Boxall, Peter. The Prosthetic Imagination: A History of the Novel as Artificial Life. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Briefel, Aviva. The Racial Hand in the Victorian Imagination. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Brooks, Baylus. Sailing East: West Indian Pirates in Madagascar. Poseidon Historical Publications, 2018.

Burwick, Frederick, and Manushag N. Powell. British Pirates in Print and Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Capuano, Peter, and Sue Zemka. Victorian Hands: The Manual Turn in Nineteenth-Century Body Studies. Ohio State University Press, 2020.

Carroll, Ross. Uncivil Mirth: Ridicule in Enlightenment Britain, Princeton, 2021.

“A Conversation between an English Sailor and a French Barber.” The Telegraph, 16 May 1796, p. 4.

Corcuera, Alfonso Muñoz. “The True Identity of Captain Hook.” Barrie, Hook, and Peter Pan: Studies in Contemporary Myth / Estudios sobre un mito contemporáneo, edited by Ed. Alfonso Muñoz Corcuera and Elisa T. Di Biase. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012, pp. 66-90.

Daen, Laurel. “‘A hand for the one-handed’: Prosthesis User-Inventions.” Rethinking Modern Prostheses in Anglo-American Commodity Cultures, 1820-1939, edited by Claire L. Jones. Manchester University Press, 2017, pp. 93-113.

Defoe, Daniel. An Essay upon Projects. London: Tho. Cockerill, 1697.

—. The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe. London, 1719. The Novels of Daniel Defoe, ed. W. R. Owens, vol. 1, Pickering & Chatto, 2008.

Defoe, Daniel [attributed]. A General History of the Pyrates. Edited by Manuel Schonhorn, Dover, 1972.

Derenzy, George Webb. Enchiridion: Or, a Hand for the One-Handed, London: T. and G. Underwood, 1822.

Deutsch, Helen and Felicity Nussbaum, editors. Defects: Engendering the Modern Body. The University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Dougherty, Kerry. “University’s Statue Has History Buffs up in Arms.” The Virgini-an-Pilot, July 19, 2007, https://www.pilotonline.com/2007/07/19/universitys-statue-has-history-buffs-up-in-arms.