Reading: ➢ closet, n. v. Oxford English Dictionary

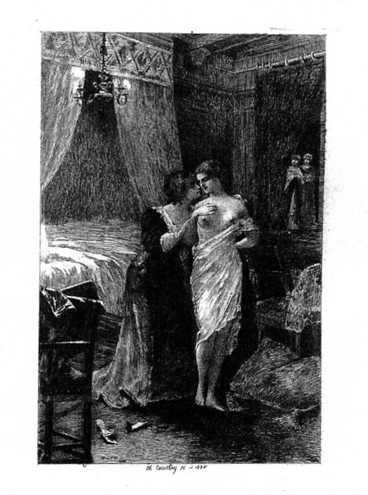

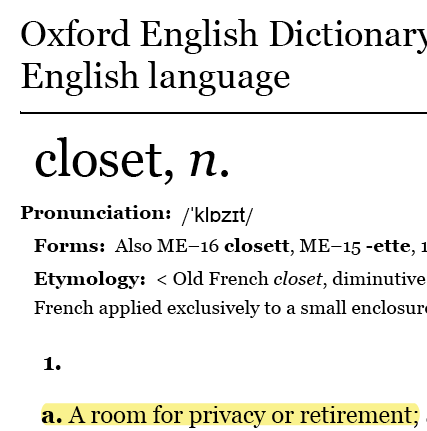

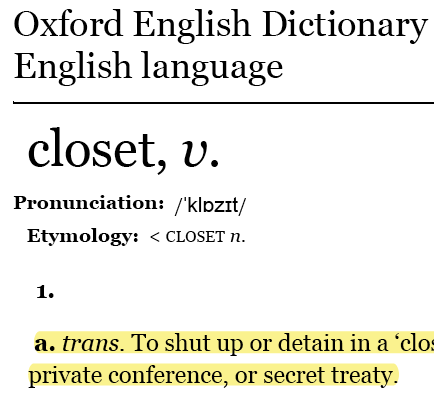

We also explore the use of the word as a general metaphor for privacy and seclusion. Some of these metaphors are negatively charged: closet as a marker of “mere theories as opposed to practical measures” (1c) or of painful, shameful secrets, including, especially since the late 1960s, secrets about one’s sexuality (3c, 3d, and 10b). Other metaphors are more neutral: closet as an analogy for a hidden interior site—”the Closet of your Conscience” (6b)—or as an adjective that qualifies a particular experience or thing as inward—”closet-sins” as opposed to “stage-sins” (10a). It is not surprising that, as the private room known by this name proliferated in English culture, closet began regularly to be used as a verb meaning “to retreat,” whether alone or—as in the title of Allan-Fraser’s painting (Figure 5)—with another person. With reference to such events as the Glorious Revolution, the lapse of the Print Licensing Act, and the founding of the Royal Society and the Bank of England listed on a timeline (Figure 6), my opening lecture characterizes the long eighteenth century as a period of gradual, uneven transition—from absolutism to constitutional monarchy, a land- to commodity- and money-based economy, from manuscript to print culture, and from a court public to a modern public sphere. Then, turning back to the OED definitions and citations, we consider in which of them the closet seems to encapsulate traditional values, in which of them progressive values, and in which a tension between the two. This collective interpretive work helps to ground a basic thesis of the course: that closets became central to eighteenth-century English discourse and culture because they were such flexible and such evocative spaces. |

Category Archives: Pedagogies

The Philosophy of Progress – Bobker

Readings:

➢ John Locke, Essay Concerning Human Understanding, selections

➢ John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, selections

In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke contests traditional notions of knowledge; in the Two Treatises, he contests traditional notions of government. Our discussion of excerpts from these texts gives depth to the historical transformations introduced in the opening lecture.

Our conversation about the epistemology touches on Locke’s rejection of prior models of innate knowledge. We note his special use of such terms as sensation and reflection, and explore various images of human understanding at work turning experience into ideas, including that of the “closet wholly shut from light, with only some little opening left, to let in external visible resemblances, or ideas of things without.” We then approach the political theory as a comparable rejection of top-down authority. Students become familiar with such key concepts as patriarchy/patriarchalism, the state of nature, property, social contract, civil society, and paternal power.

Finally we find links between these two foundational texts of liberal democratic thought. I ask students to think with me about how the empirical mind is served by civil society and vice versa. We also discuss contradictions and gaps within and between Locke’s epistemology and his political theory, particularly relating to the status of women. On the one hand, Locke’s (largely) universal models of learning and political engagement cut against traditional views of female cognitive and political inferiority. On the other hand, though Locke refutes the traditional equivalence of political and familial authority, he ultimately rationalizes male superiority within the family and more or less takes it as a given within the state.

Rooms for Improvement – Bobker

Reading: ➢ Samuel Pepys, Diary, selections

During the nine years he kept his Diary (1660-1669), Samuel Pepys had three closets: he constantly renovated and redecorated them, and just as constantly wrote about them. Thus the Diary serves as a valuable social historical document of the period’s rich closet culture. Social mobility was then a tricky operation, only indirectly dependent on wealth. “Rooms for Improvement,” the title of this section, underscores the multiple important roles closets played in Pepys’s efforts to climb the social ladder.

Fig. 7. Samuel van Hoogstraten, View of the Corridor © National Trust. |

Many of Pepys’s closet episodes are easy to collate with the OED entries for closet, an exercise that reinforces the range of uses and resonances of this space. Pepys undertakes concentrated solitary work in his own closets, updates his journal in them, and, on at least one occasion, retreats to a closet to pray (10 August 1662). He also builds and nurtures valuable alliances as a frequent guest in royal and noble closets and, eventually, as a host in his own. And he develops his taste by paying close attention to closet contents and décor, like the perspective painting on the door to his colleague Thomas Povey’s closet that he frequently admired. [In their authoritative University of California edition of the Diary, Robert Latham and William Matthews suggest that the painting was probably Samuel van Hoorgarten’s 1662 View of the Corridor (Figure 7), a fine example, in any case, of the baroque aestheticization of receding space.] Pepys filled his own closets with maps, decorative plates, curiosities, like the tennis-ball-sized stone he had had removed from his bladder (27 August 1664), and his books—an ever-growing and much-prized collection that he had gilded for display in purpose-built bookcases. We sketch the parameters of closet gift exchanges among the Restoration elite. One memorable series of entries details the way Pepys provoked his colleague’s mistress, Abigail Williams, by “not giving her something to her closet” (6 August 1666)–pointedly excluding her from his chosen social circle (see also 19 March 1666, 10 February 1667, 22 August 1667, 15 May 1668). |

Class discussion is also elicited by those closet episodes that underscore Pepys’s social aspirations and fraught relationships with women. Though his wife Elizabeth participates in several of Samuel’s schemes to prettify their closets (see 5 October 1663, for example), he clearly sees himself as master of all these rooms–even the one officially designated for her use. Closets feature in entries exposing Pepys’s infidelity. He corners several young lowborn women into sexual indiscretions in closets (28 November 1666, 18 February 1667, 20 June 1667) and when setting up his office closet, drills a hole so that he can spy on the maid who cleans the common area (30 June 1662). Observing Mr and Mrs Pepys’s relationships to domestic space allows us to explore the period’s new ideals of companionate marriage and female privacy, and their limits under couverture, the longstanding legal convention that subsumed a wife’s identity into that of her husband.

The personal journal is the first of several genres with close ties to the closet that we discuss over the course of the semester. We consider the type of self-relation Pepys’s Diary reflects and reinforces, paying attention to linguistic tics like his use of a sexual cipher—as in: “my wife, coming up suddenly, did find me embracing the girl con my hand sub su coats” (25 October 1668)—and reflexive language—as in: “I do thinke myself obliged to thinke myself happy and do look upon myself at this time in the happiest occasion a man can be” (26 February 1666). How and to what extent is this journal a record of inner experience? In what way is Pepys a “private” man? For students, as for other critics, there tends to be significant disagreement on these questions.

Privacy and Modernity I: The Family – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Philippe Ariès, Introduction to The History of Private Life III: The Passions of the Renaissance

➢ Michael McKeon, “Chapter 5: Subdividing Inside Spaces” in The Secret History of Domesticity:

Public, Private, and the Division of Knowledge

Because a major goal of the course is to enrich and complicate notions of both private and public, students are invited to provide synonyms any time they find themselves using either of these words in discussion or writing. In this way, we can begin to uncover and, where necessary, let go of our assumptions about both categories and the relationships between them. Excerpts from two major histories of privacy ground the rethinking we have already begun: both Philippe Ariès and Michael McKeon narrate privacy’s emergence in relation to the development of the modern family.

Ariès contrasts the communality of medieval Europe–-“private was confounded with public” (1)–-to the compartmentalized forms of nineteenth-century social life – when private and public separated as the family home became a refuge from a basic state of anonymity everywhere else. According to Ariès, increasingly bureaucratic governments, the flourishing of print and literacy, and internalized religious practices like confession and closet prayer were major cultural factors in the shift from communality to compartmentalization. Early modern privacy consisted not only in more intimate family interactions than ever before in more intimate rooms than ever before, but also in changing discourses and practices of selfhood, including new concerns with bodily modesty, reflexive reading and writing, and friendship, which was increasingly characterized as shared solitude.

|

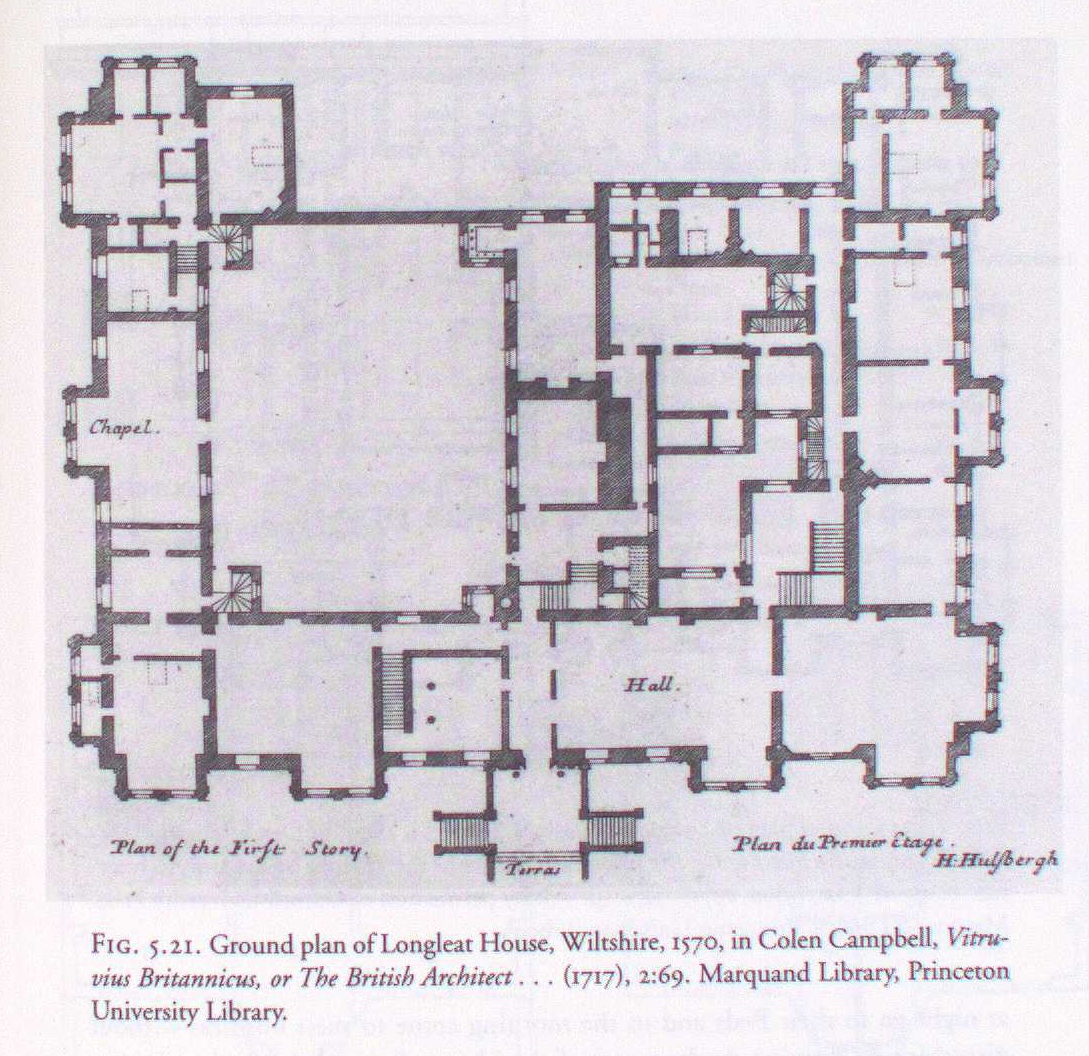

Fig. 8a. Longleat House, 1570. From Michael McKeon, The Secret History of Domesticity, 253. Marquand Library, Princeton University Library.

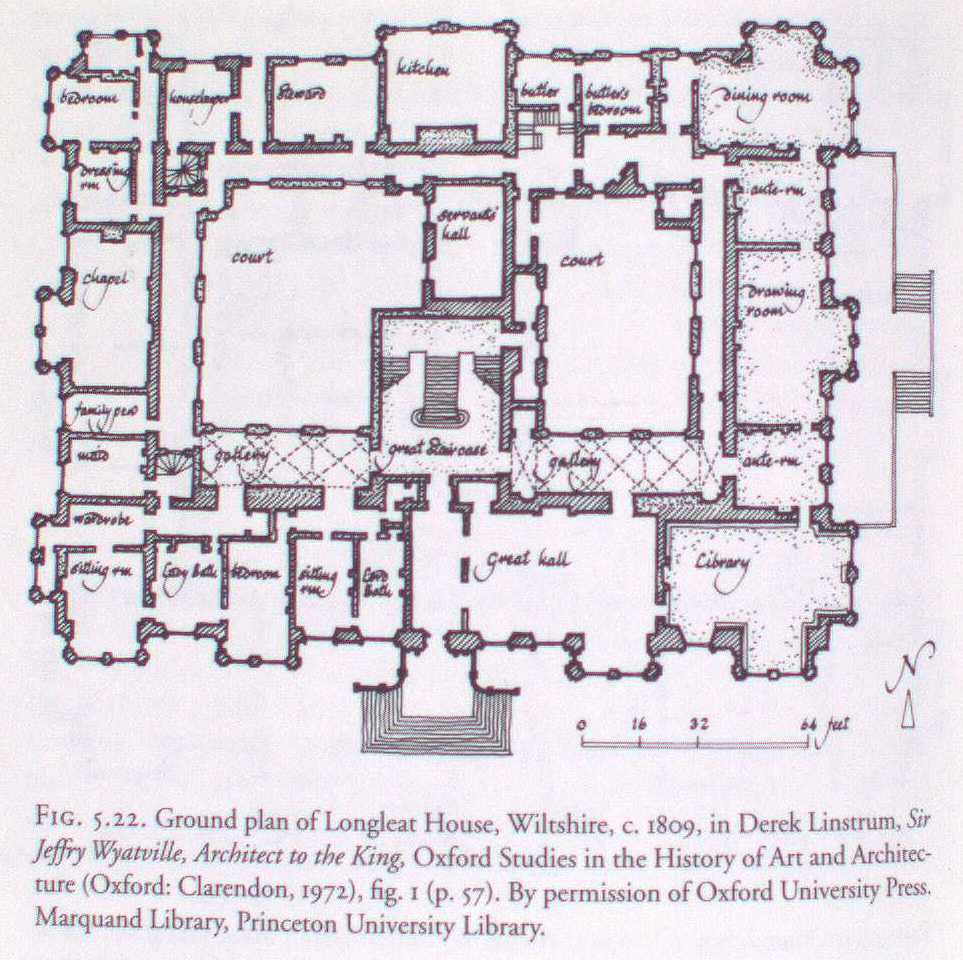

Fig. 8b. Longleat House, c1809. From Michael McKeon, Secret History of Domesticity, 254. Marquand Library, Princeton Univesrity Library. By permission of Oxford University Press. |

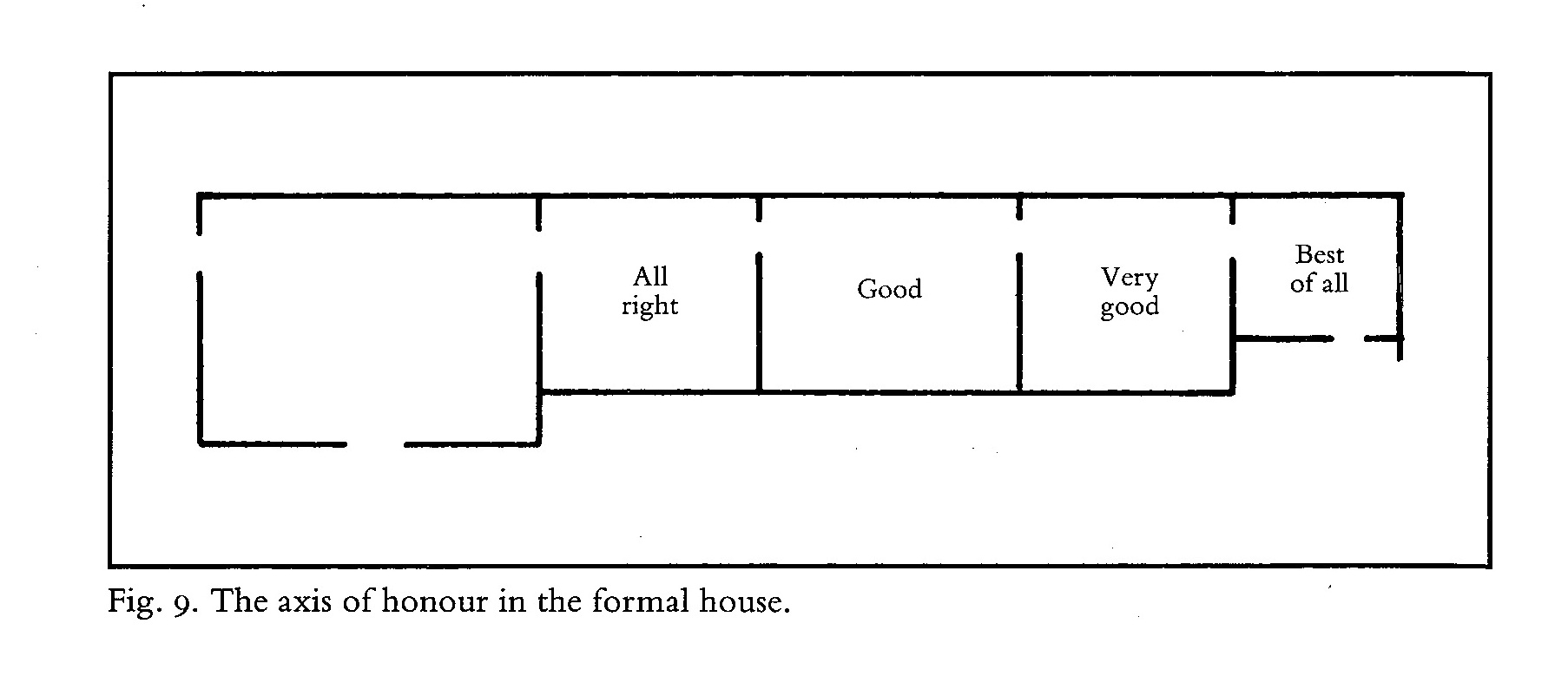

In his Secret History of Domesticity, McKeon situates the increasing coherence and complexity of the private in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries within a series of interrelated categorical and disciplinary divisions, including the separation of science from the arts and humanities and, most significantly, the separation of workplace from household. Our initial encounter with McKeon’s book focuses on his exploration of the architectural corollaries to this process. In the chapter on “Subdividing Inside Spaces,” McKeon is interested in how changing domestic designs mirrored and precipitated the conceptual evolution of privacy in the period. Privacy had traditionally been defined—and designed—as a withdrawal from the fundamental publicness of the household. Later, the generous use of corridors made individual rooms discrete and less permeable (see Figures 8a and 8b), thereby reinforcing the new feeling that privacy was a positive and distinct value. Separate rooms variously accommodated women’s desire for distance from men (and vice versa), family members’ desire for distance from servants, and the desire of any and all members of the household for distance from outside visitors. McKeon’s chapter also provides our third catalogue of the varieties of the closet and cabinet in the period, including the cabinet of curiosities and closet as study, library, boudoir, harbour of secrets, and site of secretarial business.

|

Privacy and Modernity II: The Public Sphere – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, selections

➢ Michael Warner, “Public and Private” in Public and Counterpublics

➢ Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, The Spectator, Numbers 1, 10, 217

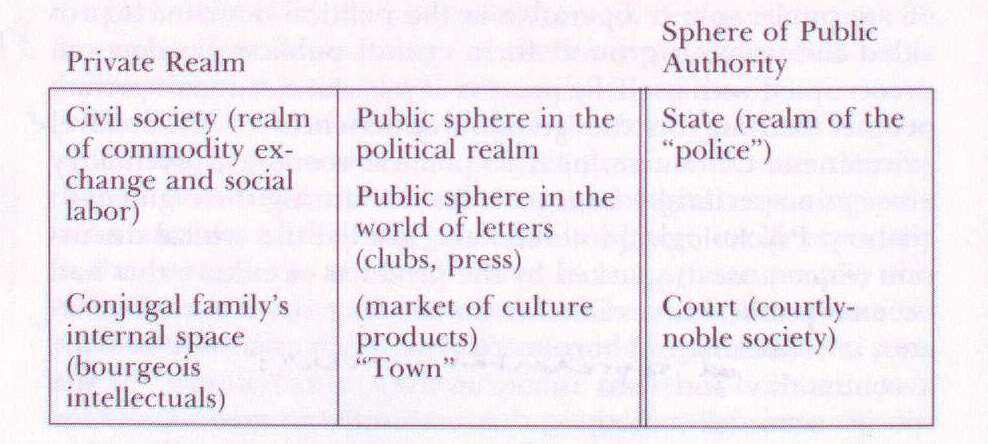

An introduction to public sphere theory extends students’ understanding of changing ideas and practices of privacy as corollaries or complements (and not necessarily in opposition) to changing ideas and practices of publicness. This section turns on Jürgen Habermas’s influential account of how new modes of political action and interpersonal connection, independent of the state, were made possible by the growth of capitalism, personal wealth, and print culture in eighteenth-century England. We note that here, not only is the family the major site in the development of privacy “in the modern sense of a saturated and free interiority” (28), but it is also the subjective condition of possibility of the modern public sphere (43).

|

Fig. 9. Public and private

Fig. 10. Private and public. Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 30.

|

With reference to three essays from Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s highly successful, daily London periodical, The Spectator (one of Habermas’s exemplary texts), we observe how print’s quick turnaround and low costs facilitated a more reciprocal relationship between authors and readers. This is most obviously manifested in the many letters from readers that Mr Spectator solicits, publishes, and engages with in print. In Number 10, when Mr Spectator declares, “I shall be ambitious to have it said of me, that I have brought Philosophy out of Closets…,” he makes the private room symbolize the antiquated, impenetrable form of intellectual authority that he explicitly rejects in favor of a more interactive mode of engagement. (As we will see in Section 7, in the eighteenth century, the closet or cabinet “opened” in fact became a very common figure for the unprecedented accessibility of commercial print.) The issue of women’s access to the public sphere is especially charged in the Spectator. Mr Spectator represents female readers as important beneficiaries of the daily guidance provided by his publication because they are naturally susceptible to frivolity and other passionate excesses, but he also seems eager to discipline female embodiment and women’s collective agency beyond the home. In Number 217, for example, Mr Spectator responds with bemused reproach to “Kitty Termagant”’s description of a “Club of She-Romps,” a wild all-female midnight gathering. Convinced by Habermas’s narrative in outline, Michael Warner emphasizes the democratic potential of modern media publics while criticizing the ways their putative universality in fact privileges heterosexual white men. Warner especially champions the idea and manifestations of counterpublics, that is virtual collectives in which the embodied conditions of gender and sexuality are not denied and repressed as in conventional publics but rather treated as “the occasion for forming publics, elaborating common worlds, making the transposition from shame to honor, from hiddenness to the exchange of viewpoints with generalized others” (61). For instance, Warner finds in the “Club of She-Romps” in Spectator Number 217 a striking illustration of an early counterpublic. This part of Warner’s argument causes some debate among students, some of whom are skeptical that this obviously satirical essay can be read so much against the grain. Warner’s discussion of a famous anecdote about Diogenes masturbating in the marketplace succinctly illustrates “the visceral force behind the moral ideas of private and public” (21). Another very helpful point of reference is his comprehensive chart of definitions (Figure 9), which elaborates the wide range of meanings of private and public, some but not all of which are opposing. We use it to review Habermas’s specific uses of the terms private and public (Figure 10) (which may seem contradictory but in fact are not) and we return to this chart often throughout the semester to make sense of our own and other current investments in these categories. |

The Courtly Closet and the Closet of Devotion – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Anthony Hamilton, Memoirs of Count Grammont, selections

➢ Edward Wettenhall, Enter into thy Closet, selections

|

|

Excerpts from Anthony Hamilton’s Memoirs of the Count Grammont, a secret history of the Restoration court, and Edward Wettenhall’s Enter into thy Closet, a frequently republished prayer manual, open up distinctive but overlapping modes of political and spiritual privacy: court favouritism and closet devotion. At court, decisions about when and to whom to grant access to the closet were exercises in arbitrary power and the status and roles of secretaries and other royal favorites were explicitly defined in relation to the closet. As one sixteenth-century secretary had put it: “To a Closet, there belongeth properly, a doore, a locke, and a key: to a Secretorie, there appertaineth incidently, Honestie, Troth, and Fidelitie.” We consider the many examples of closet relations in Hamilton’s Memoirs, focusing on (1) a funny and puzzling episode involving the Duchess of York, Miss Hobart (the Duchess’s favourite), Miss Temple (the Duchess’s favorite’s favorite), and the Restoration’s most notorious rake, the Earl of Rochester (Figures 11 and 12), (2) the author’s bond with his biographical subject, his brother-in-law Philibert de Comte de Gramont, and (3) the virtual transfer of favor to readers throughout this text and in the genre of secret history in general. We especially consider the politics of same-sex closet relations: Who gains what through relations of patronage and favoritism between people of the same sex? Under what circumstances and in what way do these relationships become erotic? What are the broader social and political implications of this kind of ambitious intimacy? At first glance, the prayer closet seems a very different space from the courtly closet. Satisfying the basic Protestant impulse to strip away Catholic mediations, the King James translation of the Bible (1611) gave a new specificity to the injunction to pray alone in Matthew 6.6: “But when thou prayest enter into thy Closet…” Along with new modes of self-examination, closet prayer formalized a special kind of closeness to God and Jesus. With reference to Wettenhall’s manual, we parse out the key components of closet prayer and the interesting notions of time and timelessness associated with this practice. Wettenhall writes that the most powerful prayers belong to those “whose daily and frequent application of themselves to the throne of grace hath rendred them there well acquainted and favourites” (29). Students are asked to think about how the discourse of favouritism connects the prayer closet to the courtly closet. We also discuss the homoerotics of closet prayer with reference to Richard Rambuss’s Closet Devotions, which argues that the prayer closet was an important site for the internalization of sexuality.

Suggested Presentation Topics: The history of court favoritism

Fig. 13: Enter into thy Closet.

|

The Cabinet of Curiosity and the Dressing Room – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Selections from The Ladies Cabinet broke Open, Modern Curiosities of Art and Nature, Cabinet of Momus,

and Cabinet of Choice Jewels

➢ Alexander Pope, “Rape of the Lock” and “The Key to the Lock”

|

Fig. 14. Franz Ertinger, Le Cabinet de la

Fig. 17: A Rich Cabinet. Frontispiece of A Rich Cabinet. |

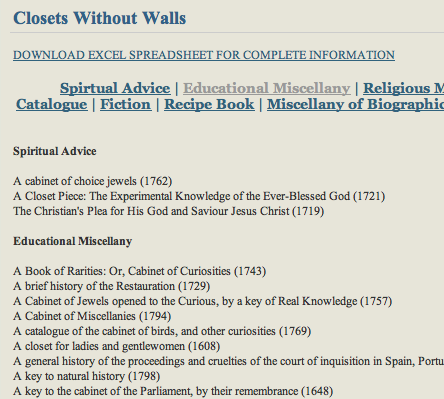

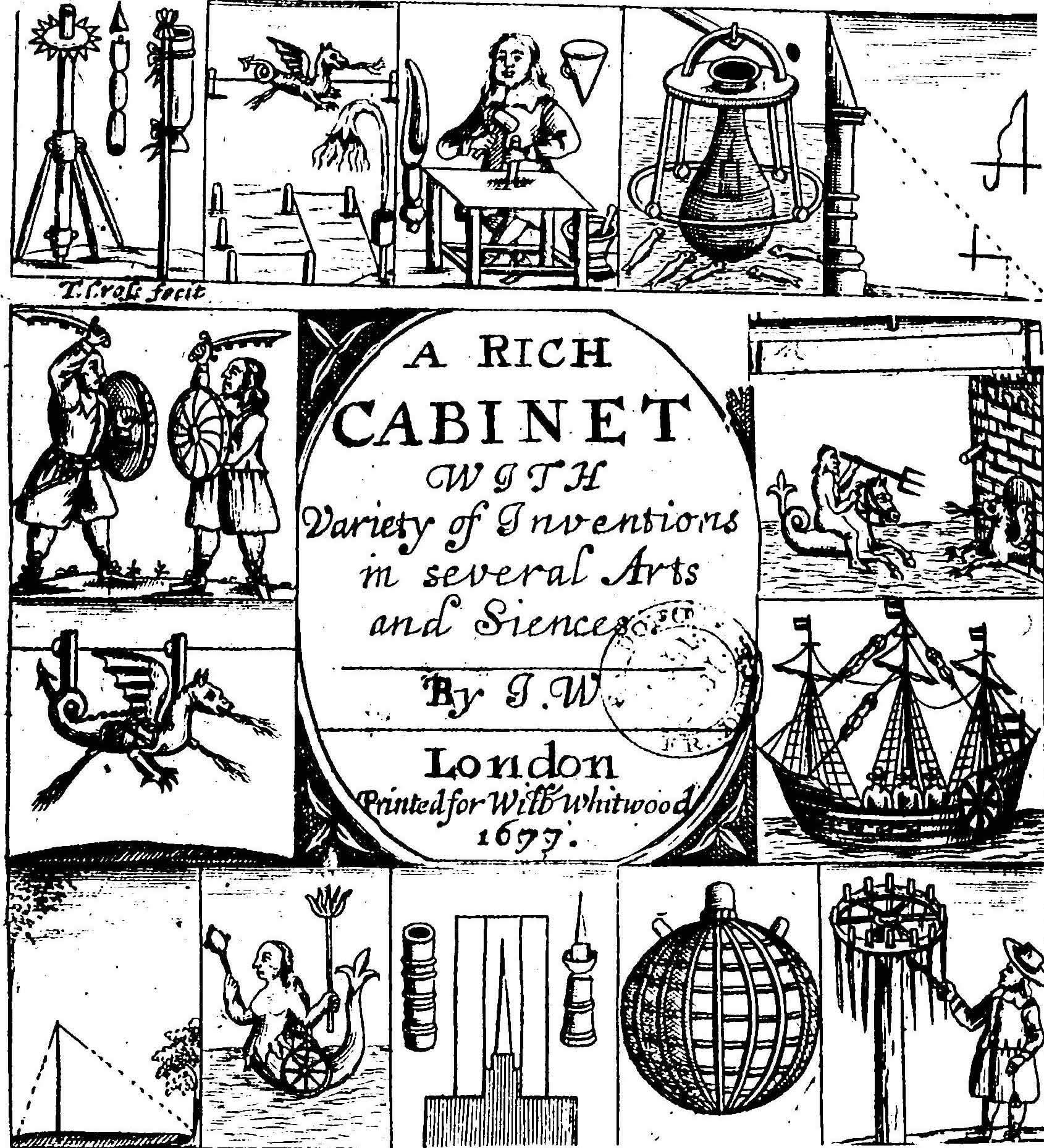

When the British elite and a growing group of merchants developed a taste for collecting in the middle of the seventeenth century, they brought into their closets freestanding wooden repositories, and the word cabinet–- from the French for “closet”–-was increasingly attached to this latter smaller enclosure (Figure 14). In the eighteenth century, cabinet-makers had a booming trade (Figure 15). Multi-sectioned, lockable cabinets permitted not only the safe storage and organization of books, art works, antiquities, natural specimens, and other curios, but also their elegant display. I briefly introduce this practice with reference to a subsection of Michael McKeon’s “Subdividing Spaces” (218-19) and Patrick Mauriès’s beautifully illustrated Cabinets of Curiosity (see especially III “The Collector: senex puerilis,” and IV “The Phantom Cabinet: 18th-19th Centuries”), emphasizing the triumph of systematic methods of organization over the collector’s subjective experience of awe or wonder. In the eighteenth century, as Mauriès explains, “The concept of the cabinet of curiosities began to change when differences became more important than correspondences. This would lead to the breaking up of the great collections and their re-allocation to specialized institutions, the naturalia to natural history museums and the artificialia to art galleries” (193). The Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, opened in 1683, housed the collection that John Tradescant had originally displayed in his private home; the British Museum, the first national public museum in the world, was founded in 1753 to exhibit the contents of the private cabinets of naturalist and collector, Sir Hans Sloane. Closets Without Walls (Figure 16) is my bibliography of 170 publications, most from eighteenth-century England, called “closets” and/or “cabinets,” many of which were also qualified as “unlocked” or “broken open.” Its title alludes to the phrase “libraries without walls,” which was coined by book and media historian Roger Chartier to refer to the textual bibliothèques— book catalogues—popular in eighteenth-century France. Whereas in the French “libraries without walls,” publishers confronted the longstanding fantasy that all the books in existence (or at least their titles) might be gathered in one place, the books in the Closets Without Walls archive highlight the important metaphorical role played by private spaces for publishers, and others in the book trade, coming to terms with the growing popularity of print in eighteenth-century England. I introduce the figurative appeal of the closet or cabinet opened with reference to the frontispiece of John White’s Rich Cabinet (Figure 17), whose array of boxes is suggestive not only of the residual chaos of natural philosophical knowledge in the seventeenth century but also of the novelty and excitement associated with their public exposure in print. To further investigate this appeal, I ask students to analyze the front matter of The Ladies Cabinet broke Open, Modern Curiosities of Art and Nature, Cabinet of Momus, and Cabinet of Choice Jewels as well as three other texts of their own choosing, which they select on the Closet Without Walls bibliography then locate on Early English Books Online or Eighteenth Century Collections Online. As the Notes column (G) on the bibliography indicates, in textual closets and cabinets, the figure of private space serves as a very flexible conceptual bridge between an elite, exclusive, manuscript-centered culture of knowledge production and exchange and a growing print culture in which accessibility was increasingly valued. The discussion of “Rape of the Lock” focuses on the new light that histories of the closet can shed on it. The dressing room was the fashionable version of the closet reserved for storing and putting on clothes, accessories, and cosmetics. Following a brief introduction to this space by way of Tita Chico’s Designing Women: The Dressing Room in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture, we explore the impact of a burgeoning consumer culture in eighteenth-century rituals of privacy, especially as depicted in the famous toilet scene at the end of Canto 1 (lines 121-48). Pope clearly both scorns and delights in his characters’ love of surfaces. We discuss if and how the quality of this ambivalence differs where the different sexes are concerned. Next we approach the poem as a sort of collector’s cabinet: a container for arranging things in relation to one another. In particular, we consider how the poem’s many odd groupings—like the “Counsel” and the “Tea” that Queen Anne “sometimes takes” (3.8) or the “twelve vast French Romances, neatly gilt,” “three Garters,” and “half a Pair of Gloves” (2.38-39) on the Baron’s altar to love—comment on the difficulties of Pope’s contemporaries in distinguishing between style and substance. Finally, with reference to the satirical paratext “The Key to the Lock,” which Pope wrote himself, we consider if and how the poem parodies the genre of secret history.

Cabinets of curiosities

|

Privy Pastoral – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Ben Jonson, “To Penshurst”

➢ Jonathan Swift, “Panegyric on the Dean,” “The Lady’s Dressing Room,”

“A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed,”

“Strephon and Chloe,” and “Cassinus and Peter”

➢ Mary Wortley Montagu, “Reasons that induced D— S— to Write a Poem Called ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’”

➢ Samuel Rolleston, Philosophical Dialogue Concerning Decency

|

|

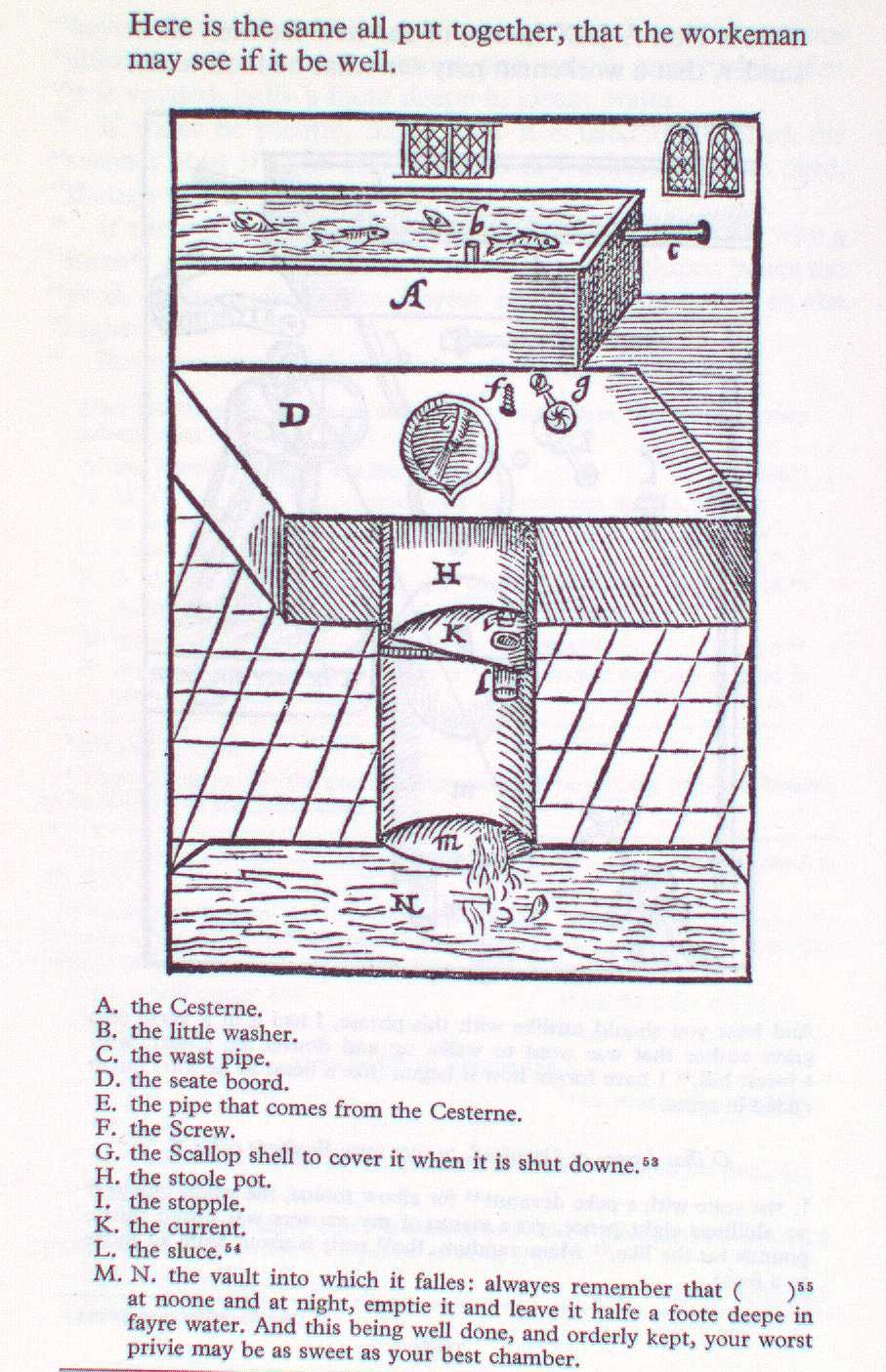

Is the desire for excretory privacy innate? Our discussion of some eighteenth-century responses to this question is informed by the material history of the water closet and the literary history of country-house poetry. A mechanized privy pot, capable of instantly flushing away waste, built into a room reserved exclusively for solitary excretion had been invented in the sixteenth century (Figure 18), but such a machine did not have wide appeal until the late eighteenth century. Before then, even among those who could have afforded to install special equipment, simple chamber pots, which could be used anywhere and emptied by servants, were vastly more common. The fundamental value encapsulated by the water closet – the fantasy of perfect excretory autonomy – was, however, already in the air, and already subject to critique, in the first half of the eighteenth century. Pastoral, georgic, and country-house poetry focus on relationships among nature (including the body and its impulses), culture (including art, labour, and agriculture), and retreat. The primary texts in this section all draw on the interrelated forms of nature poetry to depict excretory privacy as a fraught gender issue. Though each juggles a unique set of presuppositions about the extent to which culture can or should compensate for apparently natural sexual differences, all toy with the common (and enduring) belief that women are particularly shamed by the exposure of primal bodily functions. Mary Wortley Montagu’s retort to Swift’s “Lady’s Dressing Room” is an engaging way into these issues: Is there evidence in the poem that Montagu or any of her characters share Strephon’s fear of Celia’s shit? We then consider Rolleston’s Dialogue Concerning Decency as a countertext to Swift’s longest, earliest, and most explicit scatological poem. “Panegyric on the Dean” commemorates the pair of his-and-hers outdoor privies Swift had just built on the country estate of his patroness, Lady Anne Acheson, and is written for her (and in her voice). As they explore the modern ideal of complete excretory autonomy, both texts ask not only (1) whether the ideal is aligned with or contrary to nature and (2) whether it is or should be equally shared by both sexes, but also (3) whether it reinforces social or selfish impulses. These questions guide our conversation. Suggested Presentation Topics: The history of the water closet |

Epistolary Spaces – Bobker

Readings:

➢ Eliza Haywood, Love in Excess

➢ Samuel Richardson, Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded

Closet discourses and practices provide concrete tools for exploring the rise of the novel in the final weeks of the semester. We read four influential and entertaining novels in chronological sequence. Many critics have argued that the modern novel shaped and reflected the growth of bourgeois domestic ideology in eighteenth-century England. Focusing on the novel’s links to the secret history, our exploration emphasizes the gradual, uneven process of this development. Cynthia Wall has pointed out that most of the settings in eighteenth-century novels are only vaguely sketched if at all. Yet there is nevertheless a preponderance of closets and cabinets (and antechambers, keyholes, closed gardens, backdoors, backstairs, and underground passages) in them. Other clear, concrete marks of the influence of secret history on eighteenth-century novels include the elevated/public status of key characters, the elliptical rendering of certain names (such as Mr B—), and the centrality to their plots of private correspondence and sexual scandal. Joseph Highmore’s Mr. B— Finds Pamela Writing encapsulates a number of these themes. We consider how novels finally challenge the secret history’s traditional economy of value in which the importance of private affairs lies in the way they impinge upon or allegorize larger—national and/or political—concerns. In the eighteenth century, novelists were asking if and how the personal, the domestic, and ordinary people might be valued in and of themselves. McKeon’s discussion of the secret history is very helpful here (469-505) in relation to his rereading of Pamela (639-59): McKeon shows that it is the carefully crafted political aura in Richardson’s novel that invests Mr B— and Pamela’s amatory entanglement with “socio-ethical weight” (642).

Our discussions of Love in Excess and Pamela also look at how female privacy helped to lay the groundwork for the radical questioning of traditional gender roles and social hierarchies. Haywood uses the privileged, highly literate and reflexive solitude of her elite female characters to work out a new ideal of rational sexual agency for all women, dramatically revising the longstanding association of female virtue with chastity. In Richardson’s novel, Pamela’s surprising sophistication and self-awareness reflect her earlier dressing-room intimacy with her mistress, Lady B—, and the countless hours she later spends reading and writing letters in one closet or another: in other words, her exceptional access to privacy equips Pamela, morally and intellectually, to play the heroine. Ultimately, for both novelists, some substantial degree of female autonomy is the basic precondition of a good—that is, a companionate—marriage. Some students feel frustrated by the hypocrisies and contradictions in this formulation, which seems to assess female agency in terms of its advantages to men and heterosexuality. It can help to recall the older patriarchal values and practices–arranged marriages or marriages of alliance, for example—to which Haywood and Richardson were reacting.

Our study of the novel as a modern genre in the making also focuses on key scenes of private reading of Pamela and Love in Excess. Haywood is especially interested in how reading helps her curious but virtuous heroine, Melliora, to cultivate and ultimately to discipline her passion. In Pamela, Mr B— learns to love Pamela respectfully only after reading all of her letters and coming to sympathize with her suffering. We discuss how these metatextual subplots model the virtual and internal experiences of intimacy that were increasingly understood to be characteristic of novels and at the core of their moral power.

Suggested Presentation Topics:

Ros Ballaster on amatory fiction and the female reader

Eighteenth-century reading practices

Literacy in the eighteenth century

Desire and Domestic Fiction

The novel and masturbation

(Homo)Erotic Closets – Bobker

Reading: ➢ John Cleland, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure

|

Fig. 19. closet, sb.

Fig. 20. Jean-Honoré Fragonard, L’Armoire (The Closet) |

John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, the most famous English pornographic novel, focuses our attention on the erotics of privacy, and the network of associations linking privacy, sincerity, and sex. Fanny Hill announces on the first page that her narrative will present “stark, naked truth”: “I will not so much as take the pains to bestow the strip of a gauze wrapper on it, but paint situations such as they actually rose to me in nature…” Significantly, she defends the decorousness of her sexual explicitness with reference to domestic space: “The greatest men, those of the first and most leading taste, will not scruple adorning their private closets with nudities, though, in compliance with vulgar prejudices, they may not think them decent decorations of the staircase, or saloon” (1). Throughout the novel, not only do people have sex in closets and similarly enclosed spaces, but such rooms also give shape to formative solitary sexual experiences. Notably, Fanny Hill is introduced to heterosexual intercourse by spying from a closet on Mrs Brown, her first madam, and a young soldier (24), and then on Polly, one of her brothel sisters, and an Italian merchant (28). We ask if and how Cleland’s depictions of sexual voyeurism seem to serve a metatextual function akin to scenes of reading in other novels. That is, do Cleland’s scenes of virtual intimacy also serve to clarify the kind of vicarious learning the author wants his readers to do? The end of the novel provides an important focal point for musing on the novel’s apparently contradictory lessons about sex and propriety. Ultimately Fanny claims that her experiences as a prostitute have made it possible for her to recognize the morally and sensually superior pleasures of the reproductive matrimonial bed. For many critics Cleland’s turn to married love and virtue in what Fanny calls her “tail-piece of morality” (187) is a cheap parody of the expected finale of the domestic novel. This skepticism may seem less warranted if we recognize the extent to which Cleland has tried to distinguish Fanny’s reunion with Charles, her husband-to-be, from all the sexual encounters that have preceded it (181-186). Especially striking in this regard is Cleland’s metaphor aligning Charles’ penis with a maternal breast at which infants “in the motion of their little mouths and cheeks… extract the milky stream prepar’d for their nourishment.” We go on to consider the novel as a cabinet of sexual curiosities in which a wide range of sexual practices, including virgin hunting, flagellation, hair and glove fetishes, and sodomy, is gathered and displayed. While Fanny’s rhetoric of “taste” and “universal pleasure” accommodates this range (see especially 144), Cleland also links certain practices to social and/or physiological deficiencies. Indeed he often reinforces a new tendency in the period to turn on its head the traditional idea of good blood: the sexual taste of the aristocracy comes off as especially depraved. The publication and reception history of Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, succinctly summarized in Peter Sabor’s 2000 review essay, particularly highlights the importance and complexity of the novel’s oft-censored sodomitical theme. On the one hand, sex between men was virulently condemned in the period and Cleland’s novel echoes some of the dehumanizing rhetoric associated with this condemnation. On the other hand, there is strong evidence that Cleland’s own sexual preference was for men: as David Robinson discusses in his chapter on Cleland in his Closeted Writing and Gay and Lesbian Literature, it may make most sense to read this text as sympathetic to sodomites though in a roundabout way.

|

Finally, the opening chapter of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet provides a springboard for a conversation about the queer closet, then and now. The private domestic space became our most common metaphor for queer secrecy and shame with the gay and lesbian liberation movements of the 1960s and 70s. How did this special signification of closet take root and what are the implications of this term’s use in this context? Sedgwick opens some doors for speculating about the etymology of the queer closet with the selection of OED definitions she includes at the start of her Epistemology of the Closet (Figure 19). To Sedgwick’s suggestions, we add others that seem relevant from the complete OED entries for closet (Figures 2 and 3). Definition 3d. of closet, n., is especially relevant here, as is definition 1c., which suggests that one historical bridge to our current metaphor may have been the use of the closet as a symbol of a negative, stifling attachment to privacy. Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s painting, L’Armoire (translated as The Closet) (Figure 20), points up the basic spatial connection between the closet and the bad feelings following illicit experiences: near the bed and large enough to hide a lover, the freestanding wardrobe was a logical symbol of sexual shame.

Suggested Presentation Topics:

The history of pornography

Peter Sabor, “From Sexual Liberation to Gender Trouble: Reading the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure from the 1960s to the 1990s”

Thomas Laqueur, Solitary Sex: The Cultural History of Masturbation

Eve Kosowsky Sedgwick, “Introduction: Axiomatic” in Epistemology of the Closet

David Robinson, “The Closeting of Closeting: Cleland, Smollett, Sodomy, and the Critics” in Closeted Writing and Lesbian and Gay Literature: Classical, Early Modern, Eighteenth-Century

Overview – Bobker

|

Eighteenth-Century Literature and the Culture of the Closet is a course that I developed to explore the functional, narrative, and symbolic roles closets played in eighteenth-century life and literature. Focusing on discourses and practices of the closet especially helps to illuminate the changing parameters of privacy in the period and the centrality of this category to concurrent developments in politics, religion, science, architecture, gender, and sexuality. First defined as a kind of withdrawal available only to the elite, privacy became in the eighteenth century a positive category of experience, as desirable as it was variable. The course takes a special interest in how privacy shapes and reflects literary styles and genres of the period, including the secret history, the prayer manual, the anthology, the country house poem, and the novel.

I have taught this semester-long course three times—once as a multilevel, interdisciplinary undergraduate seminar at Emory University and twice as a graduate English seminar at Concordia University in Montreal. I have also incorporated aspects of this course in introductory surveys of eighteenth-century literature. When I first designed it, my research agenda was at the forefront of my mind: the course was an opportunity for me to test, refine, and expand my ideas on the proliferation of closets in eighteenth-century architecture and writing, and to work on communicating them as clearly as possible. I have returned to the course and its themes again and again because they are clearly engaging for students as well. Advanced students enjoy the many open-ended explorations. At the same time, because the question of privacy was so central in eighteenth-century Britain, and a major preoccupation for canonical figures on the syllabus such as Locke, Pepys, Haywood, Pope, and Richardson, the course works well as a general introduction to the period. There are intellectual challenges for everyone. Our objects of study are three moving targets: (1) the closet as a flexible architectural construct, (2) privacy’s evolution in relation to other historical developments of the period (especially new practices and ideas of publicness), and (3) the reciprocal relationship between changing literary forms and writers’ inventive use of closets as settings and symbols. Each of these themes invites a distinctive disciplinary orientation—those of material culture, social theory, and literary history respectively—while meta-thematic analysis of the processes of transformation—historicism—connects them all. Both depth and breadth of analysis are required, and maintaining the balance between them has been important to me each time I teach the course. On the one hand, there are a great many opportunities for creative and critical leaps. On the other hand, the specificity—the materiality—of our objects demands a special rigor and precision. Below, I explain the key historical, cultural, and theoretical ideas I have emphasized during each of the course’s eleven separate sections and I outline some of the most fruitful topics of conversation. I have found it useful initially to approach each theme on its own. After several weeks of overview (Sections 1 through 5), the course moves roughly chronologically through a range of interrelated texts (Sections 6 through 11). Early on we spend a good deal of time deciphering the closet’s range of functions and uncovering our ideas about the meaning and value of private and public—detective work that is above all about careful close reading of primary texts. Later, we enter more abstract territory as we ask how various literary genres celebrate, reinforce, or challenge different kinds of private experience, not least those of readers. Near the end of the semester, many students have pieced together a basic narrative of privacy’s emergence in and around literary form and will be ready to make their own intuitive leaps. Starting with Section 6, I have suggested presentation topics designed to familiarize the class with a range of complementary materials. Writing projects for the course have generally been a series of short response papers, in which students are asked to document their initial impressions of the readings, then a long final research paper, preceded by an annotated bibliography and prospectus, in which inquiries emerging during response papers and class discussions are extended. My students’ final essays have covered such topics as Pepys at the coffee house, Castle of Otranto as a secret history, the feminism of Swift’s scatology, Rape of the Lock as cabinet of curiosities, the feminization of privacy in Pamela and Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, status implications of the word alone in the seventeenth century, among many others: the pleasure they have taken in defining and pursuing their projects for this course has in turn been one of the greatest pleasures of the course for me as well. Please use the seminar outlines below in your classroom however you wish. I welcome your questions and comments at danielle.bobker@concordia.ca |

Gothic Collections, Gothic Chambers – Bobker

Reading: ➢ Horace Walpole, Castle of Otranto

|

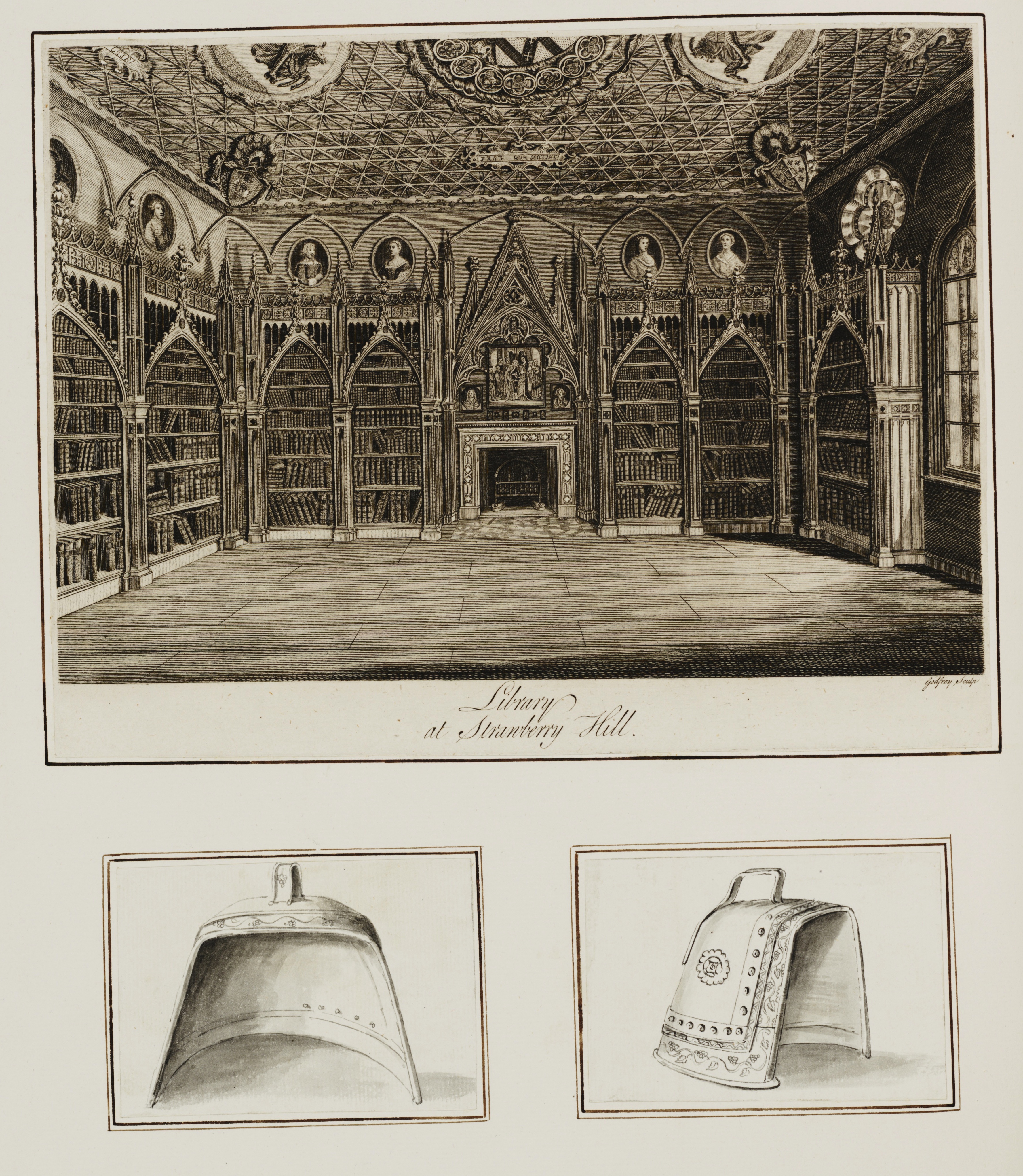

Fig. 23. Gallery at Strawberry Hill. Fig. 24. Library at Strawberry Hill. Fig. 25. The Cabinet. |

Fig. 22: Strawberry Hill, Before and After

In our last week of the course we explore the influence of Horace Walpole’s eclectic tastes on the genre of the Gothic novel he invented. Walpole’s continual renovations of his estate, Strawberry Hill (Figures 21 and 22), reflected his passion not only for feudal architecture but also for his own eccentric collections of antique coins, old and contemporary paintings, and antiquarian curios including Mary Tudor’s hair in a gold locket, Cardinal Wolsey’s red hat, and an ivory comb from the twelfth century. Walpole was not interested in the empirical systems of classification privileged by many eighteenth-century collectors. Instead he was concerned with immediate affective and imaginative charge of medieval material culture—especially its delightful dreariness, or “gloomth” as he called it—and he went to great lengths to create interior settings appropriate for the display of the things he loved (Figures 23, 24, 25, and 26). In the introduction to Castle of Otranto, Walpole writes that his inspiration for the novel came from a dream he had had about the medieval suit of armor he kept in the main staircase at Strawberry Hill (Figure 27). We approach the novel as the literary corollary of Walpole’s unorthodox antiquarianism. In particular, we pay close attention to moments where the very modern immediacy of characterization and dialogue bump up against the romantic plot, settings, and “properties”—such as Mathilda and Isabelle’s late-night exchange about their shared attraction for Theodore, for example. Ultimately, we focus on the ideological complexity of Walpole’s Gothicism. How is the novel’s melodramatic resolution a reflection of this ideological complexity? It seems clear that Walpole’s nostalgia is for the surfaces and style of Europe’s feudal past, rather than its top-down political and religious institutions. Does he succeed in showing his appreciation for the former but not the latter? Another favorite topic of conversation for students is the relationship between Walpole’s homosexuality and his taste, which we might now label as campy or kitschy.

Suggested Presentation Topics: Gothic architecture

|

|

|

Fig. 26. Beauclerk Closet, Strawberry Hill. |

Fig. 27. Staircase at Strawberry Hill. |

|

Image Gallery – Bobker

Closets Without Walls – Bobker

DOWNLOAD SPREADSHEET FOR COMPLETE INFORMATION

«A — B — C — D — E — F — G — H — I — J — L — M —P — R — S — T — V — W»

A

A Book of Rarities: Or, Cabinet of Curiosities Unlock’d (1743)

A brief history of the Restauration (1729)

A cabinet of choice jewels (1701)

A cabinet of choice jewels (1762)

A Cabinet of Fancy (1799)

A Cabinet of Jewels opened to the Curious, by a key of Real Knowledge (1757)

A Cabinet of Miscellanies (1794)

A call to the unconverted (1746)

A catalogue of a pleasing assemblage of prints… (1792)

A catalogue of a well-chosen and select collection of Pictures (1791)

A Catalogue of that Superb and Well Known Cabinet of Drawings of John Barnard, Esq. (1787)

A catalogue of the cabinet of birds, and other curiosities (1769)

A catalogue of the collection of pictures, etc. (1758)

A catalogue of the elegant cabinet of natural and artificial rarities of the late ingenious Henry Baker, Esq. (1775)

A Catalogue of the genuine, curious, and valuable (1779)

A catalogue of the valuable museum (1794)

A closet for ladies and gentlewome (1608)

A Closet Piece: The Experimental Knowledge of the Ever-Blessed God (1721)

A collection of curious prints and drawing by the best masters in Europe (1718)

A Companion to Bullock’s Museum (1799)

A coppy of verses writt in a Common Prayer Book (1710)

A general history of the proceedings and cruelties of the court of inquisition in Spain, Portugal (1731)

A key to natural history (1798)

A key to the cabinet of the Parliament, by their remembrancer (1648)

A key to the Kings cabinet (1645)

A key to the Six Per Cent Cabinet (1798)

A letter from the Man in the Moon to Mr. Anodyne Necklace (1725)

A manual history of Repentance and Impenitence (1724)

A rich cabinet of modern curiosities containing many natural and artificial conclusions… (1704)

A satyr, occasioned by the author’s survey of a scandalous pamphlet intituled, the King’s cabanet opened (1645)

A Thousand Notable Things on Various Subjects (1776)

A true narration of the surprizall of sundry cavaliers (1642)

A vindication of King Charles (1648)

An Account of a Useful Discovery (1756)

Apollo’s Cabinet or the Muses Delight (1757)

Aristotle’s Last Legacy (1711)

Art’s Master-Piece (1768)

Beautiful Cabinet Pictures (1798)

Cabinet Litteraire (1796)

Cabinet of Curiosities, No. 1 (1795)

Catalogue of the geniune (1798)

Catalogue of the intire Cabinet of Capital Drawings, collected by the late Greffier Francois Fagel (1799)

Christ’s famous titles (1728)

Coins and medals, in the cabinets of the Earl of Fife (1796)

Copys of several conferences and meetings (1790)

Cupid’s Cabinet Open’d (1750)

Cupids cabinet unlock’t (1641)

Curiosities: or, the cabinet of nature (1637)

Curtius’s Grand Cabinet of Curiosities (1800)

Delights for young Men and Maids (1725)

Duties of the Closet (1732)

Elegant and Copious History of France. Number 1. (1791)

Elegant Drawing and Cabinet Pictures (1785)

England’s choice cabinet of rarities; or The famous Mr. Wadham’s last golden legacy (1700)

England’s Mournful Monument (1714)

Every Lady her own Physician or the Closet Companion (1788)

Flower-Garden Display’d (1732)

For the Inspection of the CuriousFor the inspection of the curious…a cabinet of royal figures (1785)

Fragment of the chronicles of Zimri the Refiner (1753)

Gale’s Cabinet of Knowledge (1796)

Gloria Britannorum or, The British Worthies (1733)

History of Mother Bunch of the West (1797)

History of Mother Bunch of the West, Part the Second (1797)

Hocus Pocus (1715)

Incomparable varieties (1740)

Instructions for a prince (1779)

Jocabella, or a cabinet of conceit (1640)

Ladies Cabinet broke open, Part 1 (1718)

Letters, poems, and tales (1718)

Lineal Arithmetic (1798)

M—-C L—-N’s cabinet broke open (1750)

Miss C–Y’s cabinet of curiosities (1765)

Mist’s Closet Broke Open (1728)

Monthly Beauties (1793)

Mother Bunch’s Closet broke open…Part the Second (1800)

Mrs. Pilkington’s Jests (1764)

Particulars of and conditions of sale for a large and valuable estate called Goldings (1770)

Phylaxa Medinae. The cabinet of physick (1799)

Proposals for publishing by subscription from the curious and elaborate works of Thomas Simon (1753)

Psalmes of confession found in the cabinet of the most excellent King of Portinga (1596)

Religion the most delightful employment (1739)

Ruperts sumpter, and private cabinet rifled (1644)

Seven conferences held in the King of France’s Cabinet of Paintings (1740)

Specimens of British Minerals selected from the Cabinet of Philip Rasleigh (1797)

Sunday Thoughts .4 (1781)

Thane’s second Catalogue (1773)

The accomplish’d Lady’s Delight (1706)

The Believer’s Golden Chain (1763)

The Book of Psalms Made Fit for the Closet with Collects and Prayers (1719)

The British Phoenix (1762)

The Cabinet (1797)

The Cabinet (1754)

The Cabinet of Beasts (1800)

The Cabinet of Genius (1787)

The Cabinet of Love (1792)

The Cabinet of Momus and Caledonian Humorist (1786)

The cabinet of the arts (1799)

The cabinet of True Attic Wit (1783)

The cabinet of wit (1797)

The Christian mans closet (1591)

The Christian’s Closet-Piece: Being An Exhortation to all People To forsake their Sins, Which too much Reign in the present Age: As Pride, Envy, … (1770)

The Christian’s duty from the sacred scriptures (1730)

The Christian’s New Year’s Gift: containing a companion (1764)

The Christian’s Plea for His God and Saviour Jesus Christ (1719)

The Christian’s Preparation for the worthy receiving of the Holy Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper (1772)

The chyrugians closet (1630)

The Closet Companion (1791)

The Closet of Counsells conteining the advice of divers philosophers (1569)

The Compleat English and French Vermin-Killer (1710)

The Copper Plate Magazine (1792)

The Country Physician (1703)

The Cyprian Cabinet (1783)

The Female Pilgrim1 (1762)

The French Momus (1718)

The General State of Education in the Universities (1759)

The Gentleman and Lady’s Palladium (1752)

The Genuine Letters of Mary Queen of Scots to James Earl of Bothwell (1726)

The Golden Cabinet (1790)

The Golden Cabinet (1793)

The Golden Cabinet (1765)

The housekeeper’s valuable present (1790)

The Irish Cabinet (1746)

The Irish cabinet: or His Majesties secret papers (1646)

The Key to the kings cabinet-counsell (1644)

The King of Scotlands negotiations at Rome (1650)

The Kings cabinet opened (1645)

The Ladies Cabinet (1743)

The ladies cabinet opened (1639)

The Lady’s companion (1743)

The Laird of Cool’s Ghost (1786)

The Last Night (1790)

The Lord George Digby’s cabinet and Dr Goff’s negotiations (1646)

The Lovers Cabinet (1755)

The Modern Family Physician (1783)

The Muses Cabinet (1771)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 1 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 2 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 3 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 4 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 5 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 6 (1799)

The New Week’s Preparation for a Worthy Receiving of the Lords Supper (1770)

The Oxford Cabinet (1797)

The Parallel (1762)

The Parents Pious Gift (1704)

The Phenix Volume One (1707)

The Pleasing Instructor (1756)

The Poor Man’s Help, and Young Man’s Guide (1709)

The private tutor to the british youth (1764)

The rich cabinet furnished with varietie of excellent discriptions (1616)

The riches and extent of free grace displayed (1772)

The Royal Jester (1792)

The second part of Mother Bunch of the West (1750)

The Second Volume of the Phenix (1707)

The Spirit of Liberty (1770)

The state of France (1760)

The treasurie of commodious conceits (1573)

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol. 2 (1795)

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol.1 (1795)

To a vertuous and judicious lady who (for the exercise of her devotion) built a closet (1646)

To be seen in Curtius’s Cabinet of Curiosities (1792)

Two spare keyes to the Jesuites cabinet (1632)

Vox Populi (1774)

Who Runs next (1715)

Wit’s Cabinet (1715)

Closets Without Walls – Bobker

DOWNLOAD SPREADSHEET FOR COMPLETE INFORMATION

«1500 — 1550 — 1600 — 1650 — 1700 — 1710 — 1720 — 1730 — 1740 — 1750 — 1760 — 1770 — 1780 — 1790 — 1800 »

1569 The Closet of Counsells conteining the advice of divers philosophers

1573 The treasurie of commodious conceits

1591 The Christian mans closet

1596 Psalmes of confession found in the cabinet of the most excellent King of Portinga

1608 A closet for ladies and gentlewomen

1616 The rich cabinet furnished with varietie of excellent discriptions

1630 The chyrugians closet

1632 Two spare keyes to the Jesuites cabinet

1637 Curiosities: or, the cabinet of nature

1639 The ladies cabinet opened

1640 Jocabella, or a cabinet of conceit

1641 Cupids cabinet unlock’t

1642 A true narration of the surprizall of sundry cavaliers

1644 Ruperts sumpter, and private cabinet rifled

The Key to the kings cabinet-counsell

1645 A key to the Kings cabinet

A satyr, occasioned by the author’s survey of a scandalous pamphlet intituled, the King’s cabanet opened

The Kings cabinet opened

1646 The Irish cabinet: or His Majesties secret papers

The Lord George Digby’s cabinet and Dr Goff’s negotiations

To a vertuous and judicious lady who (for the exercise of her devotion) built a closet

1648 A key to the cabinet of the Parliament, by their remembrancer

A vindication of King Charles

1650 The King of Scotlands negotiations at Rome

1700 England’s choice cabinet of rarities; or The famous Mr. Wadham’s last golden legacy

1701 A cabinet of choice jewels

1703 The Country Physician

1704 The Parents Pious Gift

A rich cabinet of modern curiosities containing many natural and artificial conclusions…

1706 The accomplish’d Lady’s Delight

1707 The Second Volume of the Phenix

The Phenix Volume One

1709 The Poor Man’s Help, and Young Man’s Guide

1710 The Compleat English and French Vermin-Killer

A coppy of verses writt in a Common Prayer Book

1711 Aristotle’s Last Legacy

1714 England’s Mournful Monument

1715 Hocus Pocus

Who Runs next

Wit’s Cabinet

1718 A collection of curious prints and drawing by the best masters in Europe

Ladies Cabinet broke open, Part 1

Letters, poems, and tales

The French Momus

1719 The Book of Psalms Made Fit for the Closet with Collects and Prayers

The Christian’s Plea for His God and Saviour Jesus Christ

1721 A Closet Piece: The Experimental Knowledge of the Ever-Blessed God

1724 A manual history of Repentance and Impenitence

1725 A letter from the Man in the Moon to Mr. Anodyne Necklace

Delights for young Men and Maids

1726 The Genuine Letters of Mary Queen of Scots to James Earl of Bothwell

1728 Mist’s Closet Broke Open

Christ’s famous titles

1729 A brief history of the Restauration

1730 The Christian’s duty from the sacred scriptures

1731 A general history of the proceedings and cruelties of the court of inquisition in Spain, Portugal

1732 Duties of the Closet

Flower-Garden Display’d

1733 Gloria Britannorum or, The British Worthies

1739 Religion the most delightful employment

1740 Incomparable varieties

Seven conferences held in the King of France’s Cabinet of Paintings

1743 The Ladies Cabinet

A Book of Rarities: Or, Cabinet of Curiosities Unlock’d

The Lady’s companion

1746 The Irish Cabinet

A call to the unconverted

1750 Cupid’s Cabinet Open’d

M—-C L—-N’s cabinet broke open

The second part of Mother Bunch of the West

1752 The Gentleman and Lady’s Palladium

1753 Proposals for publishing by subscription from the curious and elaborate works of Thomas Simon

Fragment of the chronicles of Zimri the Refiner

1754 The Cabinet

1755 The Lovers Cabinet

1756 The Pleasing Instructor

An Account of a Useful Discovery

1757 Apollo’s Cabinet or the Muses Delight

A Cabinet of Jewels opened to the Curious, by a key of Real Knowledge

1758 A catalogue of the collection of pictures, etc.

1759 The General State of Education in the Universities

1760 The state of France

1762 The British Phoenix

The Female Pilgrim

The Parallel

A cabinet of choice jewels

1763 The Believer’s Golden Chain

The private tutor to the british youth

1764 The Christian’s New Year’s Gift: containing a companion

Mrs. Pilkington’s Jests

1765 The Golden Cabinet

Miss C–Y’s cabinet of curiosities

1768 Art’s Master-Piece

1769 A catalogue of the cabinet of birds, and other curiosities

1770 The Christian’s Closet-Piece: Being An Exhortation to all People To forsake their Sins, Which too much

Reign in the present Age: As Pride, Envy, …

The New Week’s Preparation for a Worthy Receiving of the Lords Supper

Particulars of and conditions of sale for a large and valuable estate called Goldings

The Spirit of Liberty

1771 The Muses Cabinet

1772 The riches and extent of free grace displayed

The Christian’s Preparation for the worthy receiving of the Holy Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper

1773 Thane’s second Catalogue

1774 Vox Populi

1775 A catalogue of the elegant cabinet of natural and artificial rarities of the late ingenious Henry Baker, Esq.

1776 A Thousand Notable Things on Various Subjects

1779 A Catalogue of the genuine, curious, and valuable

Instructions for a prince

1781 Sunday Thoughts .4

1783 The cabinet of True Attic Wit

The Cyprian Cabinet

The Modern Family Physician

1785 Elegant Drawing and Cabinet Pictures

For the Inspection of the CuriousFor the inspection of the curious…a cabinet of royal figures

1786 The Laird of Cool’s Ghost

The Cabinet of Momus and Caledonian Humorist

1787 A Catalogue of that Superb and Well Known Cabinet of Drawings of John Barnard, Esq.

The Cabinet of Genius

1788 Every Lady her own Physician or the Closet Companion

1790 The housekeeper’s valuable present

The Last Night

The Golden Cabinet

Copys of several conferences and meetings

1791 A catalogue of a well-chosen and select collection of Pictures

Elegant and Copious History of France. Number 1.

The Closet Companion

1792 The Copper Plate Magazine

A catalogue of pleasing assemblage of prints…

The Cabinet of Love

The Royal Jester

To be seen in Curtius’s Cabinet of Curiosities

1793 Monthly Beauties

The Golden Cabinet

1794 A catalogue of the valuable museum

A Cabinet of Miscellanies

1795 Cabinet of Curiosities, No. 1

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol.1

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol. 2

1796 Cabinet Litteraire

Coins and medals, in the cabinets of the Earl of Fife

Gale’s Cabinet of Knowledge

1797 History of Mother Bunch of the West

History of Mother Bunch of the West, Part the Second

The Oxford Cabinet

Specimens of British Minerals selected from the Cabinet of Philip Rasleigh

The Cabinet

The cabinet of wit

1798 A key to natural history

A key to the Six Per Cent Cabinet

Lineal Arithmetic

Beautiful Cabinet Pictures

Catalogue of the geniune

1799 The Naturalist’s Pocket 1

The Naturalist’s Pocket 2

The Naturalist’s Pocket 3

The Naturalist’s Pocket 4

The Naturalist’s Pocket 5

The Naturalist’s Pocket 6

Phylaxa Medinae. The cabinet of physick

Catalogue of the intire Cabinet of Capital Drawings, collected by the late Greffier Francois Fagel

A Cabinet of Fancy

The cabinet of the arts

A Companion to Bullock’s Museum

1800 The Cabinet of Beasts

Curtius’s Grand Cabinet of Curiosities

Mother Bunch’s Closet broke open…Part the Second

Closets Without Walls – Bobker

DOWNLOAD SPREADSHEET FOR COMPLETE INFORMATION

Spirtual Advice | Educational Miscellany | Religious Miscellany | Miscellany of Art & Music | Miscellany

Catalogue | Fiction | Recipe Book | Miscellany of Biographical Material | Literary Miscellany | Historical Miscellany

Spiritual Advice

A cabinet of choice jewels (1762)

A Closet Piece: The Experimental Knowledge of the Ever-Blessed God (1721)

The Christian’s Plea for His God and Saviour Jesus Christ (1719)

Educational Miscellany

A Book of Rarities: Or, Cabinet of Curiosities (1743)

A brief history of the Restauration (1729)

A Cabinet of Jewels opened to the Curious, by a key of Real Knowledge (1757)

A Cabinet of Miscellanies (1794)

A catalogue of the cabinet of birds, and other curiosities (1769)

A closet for ladies and gentlewomen (1608)

A general history of the proceedings and cruelties of the court of inquisition in Spain, Portugal (1731)

A key to natural history (1798)

A key to the cabinet of the Parliament, by their remembrance (1648)

A key to the Six Per Cent Cabinet (1798)

A rich cabinet of modern curiosities containing many natural and artificial conclusions… (1704)

A satyr, occasioned by the author’s survey of a scandalous pamphlet intituled, the King’s cabanet opened (1645)

A Thousand Notable Things on Various Subjects (1776)

A true narration of the surprizall of sundry cavaliers (1642)

An Account of a Useful Discovery (1756)

Aristotle’s Last Legacy (1711)

Art’s Master-Piece (1768)

Cabinet of Curiosities, No. 1 (1795)

Cupids cabinet unlock’t (1641)

Curiosities: or, the cabinet of nature (1637)

Delights for young Men and Maids (1725)

Elegant and Copious History of France. Number 1. (1791)

Every Lady her own Physician or the Closet Companion (1788)

Gale’s Cabinet of Knowledge (1796)

Gloria Britannorum or, The British Worthies (1733)

History of Mother Bunch of the West (1797)

History of Mother Bunch of the West, Part the Second (1797)

Hocus Pocus (1715)

Instructions for a prince (1779)

Jocabella, or a cabinet of conceit (1640)

Ladies Cabinet broke open, Part 1 (1718)

Lineal Arithmetic (1798)

Monthly Beauties (1793)

Mother Bunch’s Closet broke open…Part the Second (1800)

Mrs. Pilkington’s Jests (1764)

Phylaxa Medinae. The cabinet of physic (1799)

Ruperts sumpter, and private cabinet rifled (1644)

Seven conferences held in the King of France’s Cabinet of Paintings (1740)

Specimens of British Minerals selected from the Cabinet of Philip Rasleigh (1797)

The accomplish’d Lady’s Delight (1706)

The British Phoenix (1762)

The Cabinet (1754)

The Cabinet (1797)

The Cabinet of Genius (1787)

The Cabinet of Momus and Caledonian Humorist (1786)

The cabinet of True Attic Wit (1783)

The chyrugians closet (1630)

The Closet of Counsells conteining the advice of divers philosophers (1569)

The Complete English and French Vermin-Killer (1710)

The Country Physician (1703)

The Country-Man’s Vade-Mecum (1709)

The Female Pilgrim (1762)

The General State of Education in the Universities (1759)

The Gentleman and Lady’s Palladium (1752)

The Golden Cabinet (1790)

The housekeeper’s valuable present (1790)

The Irish Cabinet (1746)

The Ladies Cabinet (1743)

The ladies cabinet opened (1639)

The Lady’s companion (1743)

The Lovers Cabinet (1755)

The Modern Family Physician (1783)

The Muses Cabinet (1771)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 1 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 2 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 3 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 4 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 5 (1799)

The Naturalist’s Pocket 6 (1799)

The Parallel (1762)

The Phenix Volume One (1707)

The Pleasing Instructor (1756)

The Poor Man’s Help, and Young Man’s Guide (1709)

The private tutor to the british youth (1763)

The rich cabinet furnished with varietie of excellent discriptions (1616)

The Royal Jester (1792)

The second part of Mother Bunch of the West (1750)

The Second Volume of the Phenix (1707)

The Spirit of Liberty (1770)

The state of France (1760)

The treasurie of commodious conceits (1573)

To be seen in Curtius’s Cabinet of Curiosities (1792)

Two spare keyes to the Jesuites cabinet (1632)

Vox Populi (1774)

Wit’s Cabinet (1715)

Religious Miscellany

A call to the unconverted (1746)

A copy of verses writt in a Common Prayer Book (1710)

A manual history of Repentance and Impenitence (1724)

Christ’s famous titles (1728)

Duties of the Closet (1732)

Religion the most delightful employment (1739)

Sunday Thoughts (1781)

The Book of Psalms Made Fit for the Closet with Collects and Prayers (1719)

The Christian mans closet (1591)

The Christian’s Closet-Piece: Being An Exhortation to all People To forsake their Sins, Which too much Reign in the present Age: As Pride, Envy, … (1770)

The Christian’s duty from the sacred scriptures (1730)

The Christian’s New Year’s Gift: containing a companion (1764)

The Christian’s Preparation for the worthy receiving of the Holy Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper (1772)

The Closet Companion (1791)

The New Week’s Preparation for a Worthy Receiving of the Lords Supper (1770)

The Parents Pious Gift (1704)

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol.1 (1795)

The world’s doom: or the cabinet of fate unlocked. Vol.2 (1795)

To a vertuous and judicious lady who (for the exercise of her devotion) built a closet (1646)

Miscellany of Art & Music

A cabinet of choice jewels (1701)

A catalogue of a well-chosen and select collection of Pictures (1791)

Apollo’s Cabinet or the Muses Delight (1757)

Cupid’s Cabinet Open’d (1750)

Flower-Garden Display’d (1732)

For the Inspection of the Curious (1785)

Proposals for publishing by subscription from the curious and elaborate works of Thomas Simon (1753)

The Cabinet of Beasts (1800)

The cabinet of the arts (1799)

The Copper Plate Magazine (1792)

The Oxford Cabinet (1797)

Miscellany

England’s choice cabinet of rarities; or The famous Mr. Wadham’s last golden legacy (1700)

Catalogue

A catalogue of pleasing assemblage of prints (1792)

A Catalogue of that Superb and Well Known Cabinet of Drawings of John Barnard, Esq. (1787)

A catalogue of the collection of pictures, etc. (1758)

A catalogue of the elegant cabinet of natural and artificial rarities of the late ingenious Henry Baker, Esq. (1775)

A Catalogue of the genuine, curious, and valuable (1779)

A catalogue of the valuable museum (1794)

A collection of curious prints and drawing by the best masters in Europe (1718)

A Companion to Bullock’s Museum (1799)

Beautiful Cabinet Pictures (1798)

Cabinet Litteraire (1796)

Catalogue of the genuine (1798)

Catalogue of the intire Cabinet of Capital Drawings, collected by the late Greffier Francois Fagel (1799)

Coins and medals, in the cabinets of the Earl of Fife (1796)

Curtius’s Grand Cabinet of Curiosities (1800)

Elegant Drawing and Cabinet Pictures (1785)

For the inspection of the curious (1785)

M—-C L—-N’s cabinet broke open (1750)

Particulars of and conditions of sale for a large and valuable estate called Goldings (1770)

Thane’s second Catalogue (1773)

The Last Night (1790)

Fiction

A Cabinet of Fancy (1799)

A letter from the Man in the Moon to Mr. Anodyne Necklace (1725)

Copys of several conferences and meetings (1790)

Fragment of the chronicles of Zimri the Refiner (1753)

Miss C–Y’s cabinet of curiosities (1765)

The Cabinet of Love (1792)

The cabinet of wit (1797)

The Cyprian Cabinet (1783)

The Female Pilgrim (1762)

The Laird of Cool’s Ghost (1786)

Recipe Book

Miscellany of Biographical Materials

A key to the Kings cabinet (1645)

A vindication of King Charles (1648)

England’s Mournful Monument (1714)

Letters, poems, and tales (1718)

Mist’s Closet Broke Open (1728)

Psalmes of confession found in the cabinet of the most excellent King of Portinga (1596)

The French Momus (1718)

The Genuine Letters of Mary Queen of Scots to James Earl of Bothwell (1728)

The Irish cabinet: or His Majesties secret papers (1646)

The King of Scotlands negotiations at Rome (1650)

The Kings cabinet opened (1645)

The Lord George Digby’s cabinet and Dr Goff’s negotiations (1646)

The Queen’s Closet Opened (undated)

The riches and extent of free grace displayed (1772)

Who Runs next (1715)

Literary Miscellany

Historical Miscellany

The Key to the kings cabinet-counsell (1765)

Bibliography – Bobker

Addison, Joseph and Richard Steele. The Spectator. Ed. Donald Bond. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Print.

Ariès, Philippe. Introduction. The History of Private Life III: The Passions of the

Renaissance. Ed. Roger Chartier. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Armstrong, Nancy. Desire and Domestic Fiction. New York: Oxford UP, 1990. Print.

Ballaster, Ros. Seductive Forms: Women’s Amatory Fiction from 1684 to 1740. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1992. Print.

Brooks, Thomas. Cabinet of Choice Jewels Or, A Box of precious Ointment. EEBO. London: 1669. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Cabinet of Momus. London: 1786. ECCO. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Chartier, Roger. “Libraries without Walls.” Future Libraries. Spec. Issue of Representations 42 (Spring 1993): 38-52. Print.

Chico, Tita. Designing Women: The Dressing Room in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2005. Print.

Cleland, John. Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print. Oxford World’s Classics. Print.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Boston: Routledge, 1979. Print.

Edson, Michael. “‘A Closet or a Secret Field’: Horace, Protestant Devotion and British Retirement Poetry.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 35.1 (2012): 17-41. Web. 15 Dec. 2012.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Trans. Thomas Burger. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology P, 1995. Print.

Hamilton, Anthony. Memoirs of Count Grammont. Whitefish MT: Kessinger, 2010. Print.

Haywood, Eliza. Love in Excess. Peterborough ON: Broadview, 2000. Print.

Jonson, Ben. “To Penshurst.” Norton Anthology of British Literature: Vol 1B. Ed. George M. Logan, Stephen Greenblatt, and Barbara Lewalski. New York: Norton, 2000. 1399-1401. Print.

The Ladies Cabinet broke Open. London: 1710. ECCO. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Laqueur, Thomas. Solitary Sex: The Cultural History of Masturbation. New York: Zone Books, 2003. Print.

Locke, John. Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Ed. Peter Nidditch. Oxford: Clarendon, 1979. Print.

——. Two Treatises of Government. Ed. Peter Laslett. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2000. Print.

Mauriès, Patrick. Cabinets of Curiosity. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2002. Print.

McKeon, Michael. The Secret History of Domesticity: Public, Private, and the Division of Knowledge. Baltimore MD: The Johns Hopkins UP, 2006. Print.

Modern Curiosities of Art & Nature. Extracted out of the Cabinets of the most Eminent

Personages of the French Court. London: 1685. EEBO. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Montagu, Mary Wortley. “The Reasons that Induced Dr S[wift] to Write a Poem Call’d the Lady’s Dressing Room.” Essays and Poems and Simplicity, A Comedy. Ed. Robert Halsband and Isobel Grundy. Oxford: Clarendon, 1977. Print.

Pepys, Samuel. Diary. Project Gutenberg Literary Editions. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Pope, Alexander. “Rape of the Lock” and “The Key to the Lock.” New York: Bedford, 2007. Print.

Rambuss, Richard. Closet Devotions. Durham NC: Duke UP, 1998. Print.

Richardson, Samuel. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Robinson, David M. Closeted Writing and Gay and Lesbian Literature: Classical, Early

Modern, Eighteenth-Century. Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

Rolleston, Samuel. Philosophical Dialogue Concerning Decency. London: 1751. ECCO. Web. 1 Feb. 2006.

Sabor, Peter. “From Sexual Liberation to Gender Trouble: Reading the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure from the 1960s to the 1990s.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 33.4 (2000): 561-78. Print.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosowsky. Introduction: Axiomatic. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley: U of California P, 1990. Print.

Sontag, Susan. “Notes on ‘Camp.’” Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York:

Picador, 2001. 275-92. Print.

Swift, Jonathan. Complete Poems. Ed. Pat Rogers. New Haven: Yale UP, 1983. Print.

Wall, Cynthia. “Writing Things.” The Prose of Things: Transformations of Description in the

Eighteenth Century. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2006. Print.

Walpole, Horace. Castle of Otranto. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. Print. Oxford World’s Classics.

——. The Mysterious Mother. Castle of Otranto and The Mysterious Mother. Peterborough ON: Broadview, 2003. Print.

Warner, Michael. “Public and Private.” Public and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books, 2002. Print.

Wettenhall, Edward. Enter into thy Closet. London: 1684. EEBO. Web. 30 Aug. 2007.

Works Cited – Klein

Aull, Laura L. “Students Creating Canons: Rethinking What (and Who) constitutes the Canon.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 12.3 (2012): 497-512. Print.

Ball, Cheryl, and Ryan Moeller. “Reinventing the Possibilities: Academic Literacy and New Media.” The Fibreculture Journal 10 (2007) Web. 16 Aug. 2014.

Barst, Julie M. “Pedagogical Approaches to Diversity in the English Classroom: A Case Study of Global Feminist Literature.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 13.1 (2013) 149-57. Print.

Koh, Adeline. “Introducing Digital Humanities Work to Undergraduates: An Overview.” Hybrid Pedagogy (14 Aug. 2014). Web. 23 Aug. 2014.

Keleman, Erick. “Critical Editing and Close Reading in the Undergraduate Classroom.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 12.1 (2011): 121-38. Print.

Lari, Pooneh. “The Use of Wikis for Collaboration in Higher Education.” The Professor’s Guide to Taming Technology. Leveraging Digital Media, Web 2.0. Ed. Kathleen P. King and Thomas D. Cox. Charlotte, NC: Information Age, 2011. 121-33. Print.

Marsden, Jean I. “Beyond Recovery: Feminism and the Future of Eighteenth-Century Literary Studies.” Feminist Studies 28.3 (2002): 657-62. Print.

Moskal, Jeanne. “Introduction: Teaching British Women Writers, 1750-1900.” Teaching British Women Writers, 1750-1900. Ed. Jeanne Moskal and Shannon R. Wooden. New York: Peter Lang, 2005. Print. 1-10.

Shesgreen, Sean. “Canonizing the Canonizer: A Short History of The Norton Anthology of English Literature.” Critical Inquiry 35.2 (2009): 293-318. Print.

Takayoshi, Pamela, and Cynthia L. Selfe. “Thinking about Multimodality.” Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers. Ed. Cynthia L. Selfe. New York: Hampton Press, 2007. 1-12. Print.

Weber, Elizabeth Dolly. “Lighting Their Own Path: Student-Created Wikis in the Commedia Classroom.” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture 13.1 (2012): 125-32. Print.

Reflections on the Course – Klein

The goals of the course (revisited) were to:

• introduce students to eighteenth-century British culture and eighteenth-century British women’s poetry;

• explore the interaction between the poetry of women and men in eighteenth-century Britain;

• understand the position and oppression of women in eighteenth-century Britain;

• gain an appreciation of eighteenth-century poetic forms and styles; and

• contribute to the popularization of understudied women’s literature

At the end of the course, students had acquired an appreciation of poetic forms (like sonnets, odes, and heroic couplets), read a variety of poems from the eighteenth century by English, Scottish, and American women, and had first-hand experience with literary research using both primary and secondary sources. Through in-class presentations and supplementary readings, students were also introduced to eighteenth-century culture and life in Britain and America, with particular attention paid to the position of women at the time. The course included poetry by women, both rural and London-based, well-known in their own time and obscure, rich and poor, black and white. The course focused on issues of inclusivity, diversity, feminist recovery, canonicity, and community. Students demonstrated their mastery of literary terms and analysis through their final project, and, through the wikis and class discussions, they also showed their new-found interest in the female authors we studied.

Where I feel the course could be improved was with regard to the formal elements of poetry, such as the uses of meter, rhyme, line breaks, etc. While some of these elements were covered in the course, there was not enough time to explore them in-depth. Similarly, in a full-length, semester-long course, there might have been time for students to give a second oral presentation on an element of eighteenth-century life, especially pertaining to women. Instead, the burden of introducing students to the historical period fell to me, the instructor, and was limited by time.