LIKE EVERY PROFESSOR of eighteenth-century British literature I know, I find it challenging to fill undergraduate courses in my field. The English majors who have satisfied the prerequisites for 300-level period-based courses tend to gravitate to classes they assume will straightforwardly address their concerns and reflect their experiences. Consequently, courses on eighteenth-century authors such as Daniel Defoe often get cancelled while surveys of post-modernism thrive. I have tried obvious tactics, such as revising the title of a typical eighteenth-century literature course to “Hellions and Harlots in Eighteenth-Century Novels” or teaching episodes of Survivor alongside Robinson Crusoe, to increase enrollment in my courses. “Look!” such courses implicitly scream, “I can be postmodern, too!” While sexier course titles may encourage students to window shop, it is more difficult to keep them around once they see the bewigged and beribboned men and women on the covers of the assigned books. Despite the wigs, eighteenth-century literature is unquestionably relevant to today’s political, social, and economic concerns. For example, last fall I taught an attempted rape scene in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela that was eerily prescient of Senate testimony given the same week about Brett Kavanagh’s attempt to rape a classmate in prep school. As this example shows, the past doesn’t just inform the present; in eighteenth-century terms, it is its direct descendent. But how do we overcome the misalignment between students’ assumptions about the period and the content of the literature we teach in order to keep them enrolled in our courses so that they can see it, too?

Another challenge that appears to be antithetical to the question of how to help students discern connections between the twenty-first and the eighteenth centuries is how to achieve this goal while maintaining a focus on historical and cultural specificity. One of the great pleasures of reading texts from a different time and place is to learn about the habits and assumptions of the cultures they depict and interpret. Newgate is different in significant ways from a state or federal penitentiary in the United States today. Childbirth meant something different for women when there were no antibiotics or reliable forms of birth control. Marriage would have been experienced differently by those who could not easily procure divorces. These few examples are sufficient to demonstrate that knowledge about the period is a prerequisite to the historically informed close readings of texts we expect from class discussions and essays. However, concentrating too much on historical context can backfire if it alienates students from literature they already believe is irrelevant to their lives. A successful course must not only somehow forge links between periods while also emphasizing distinctions between them, but also hone skills specified by the learning outcomes for the course. In the course I refer to in this article, the learning outcomes are as follows:

-

demonstrate competency in literary research and its applications; and

-

apply field-specific critical and theoretical methods of literary analysis to produce aesthetic, historical, and cultural assessments of literary texts.

Put more simply, the course should teach students to research and analyze literary texts and to convincingly convey their conclusions to readers and listeners. In addition to these learning outcomes, I have other goals for my students, such as teaching them to perform a compelling close reading of a complicated passage, work effectively in teams, and understand the importance of historical context to interpreting literature.

The active learning activity I call Moll Flanders on Trial effectively accomplishes all these objectives. The activity itself lasts for two weeks and will not succeed unless students have already finished and discussed Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722). Assuming you spend three weeks covering Moll Flanders, integrating this activity into your class will mean you have to devote about a third of an entire course to one novel. This is a substantial commitment that is justified because the activity teaches so much to students.

Active Learning Activities

As Cathy Davidson asserts, active learning is an “engaged form of student-centered pedagogy” that creates circumstances in which students can “learn how to become experts themselves” (8). Ideally, this strategy will promote “new ways of integrating knowledge” into students’ repertoires and inform their reading of texts throughout their lives (Davidson, 8). I incorporate at least one learning activity per novel into all my period-based upper-division undergraduate courses.i These activities may be as simple as working in a group to impersonate the style of an author. However, the ones that have proved most effective, including Moll Flanders on Trial, are longer and more involved. Regardless of their complexity, all of these activities require students to imaginatively enact some aspect or the period and its literature. Although dramatization is a definitional aspect of the learning activities I design and use in my courses, they are not acting exercises, but rather thought experiments. They necessitate interpretation of significant characteristics of the eighteenth century, such as how it conceptualizes of gender or class. The most successful activities also require students to compare and contrast these categories to modern conceptions of them and, finally, to the way students experience them. An effective learning activity lives in at least three worlds: the world of the text from which it is derived; the world of modern ideologies about the concepts it interrogates; and the student’s lived world.

Moll Flanders on Trial

The Moll Flanders on Trial activity enacts Moll’s trial recounted in Defoe’s Moll Flanders (1722), the first novel we read in my 300-level eighteenth-century novel course. Moll is charged with the felony of stealing fabric worth in excess of a shilling, the crime legal historian John Langbein identifies as “by far the most commonly prosecuted offense at the Old Bailey” (“Shaping,” 36). In Defoe’s novel, Moll is found guilty of the theft and sentenced to death, though she is ultimately transported rather than hanged. Moll Flanders on Trial takes as its basis this episode but enlarges the scope of Moll’s trial so that it encompasses larger questions about ethics, personal responsibility, and society’s obligation to protect vulnerable people. In other words, the activity is about social justice.

Trials work particularly well as class activities. As English Showalter argues of the trial that concludes Albert Camus’ The Stranger (1942), the structure of a trial stages conflicts implicit in literature. During trials, “intense human passions conflict with each other” and “in order to resolve the conflict the court must distinguish appearance from reality according to principles generally accepted by society” (45). Most importantly, “even when basic agreement is reached on what really happened,” as is the case in Moll Flanders, the “freedom of the individual often confronts the necessity for order and regulation” (Showalter, 45). As Showalter’s comments suggest, the most engaging aspect of Moll’s trial for students is whether she should be held responsible for crimes she commits in the context of a society that offers few legitimate opportunities for her to support herself. Where does individual responsibility end and collective accountability begin?

Moll Flanders on Trial is based on the adversarial division between prosecution and defense. Students replicate this structure instinctually because they have seen it represented in so many television and movie legal dramas. Each student must be assigned to either the prosecution or defense team before the activity begins. Ideally both teams will have the same number of students, but if there are an uneven number of students one team will necessarily be larger than the other. Typically I allow students to choose whether they wish to prosecute or defend Moll, at least until one of the teams is full. Initially, most students want to prosecute her, although by time the trial ends they often become more sympathetic to the defense’s arguments and critical of their own assumptions about Moll’s personal culpability. This shift in thinking is one of the most exciting aspects of the activity. Political or religious beliefs can make students resistant to scrutinizing their assumptions about the role government ought to play in providing individuals with education, health care, shelter, and opportunities to advance socially and economically. However, when they evaluate these same issues from the perspective of another period they are often able to objectively critique their own convictions.

Although Moll Flanders on Trial requires students to join legal teams representing either the defendant or the state, it is worth explaining to them that this aspect of the activity is historically inaccurate. First, victims of theft rather than the state prosecuted property crimes and did so at their own expense. The novel itself makes this clear because Moll and her friend the pawnbroker try to convince the broker she steals from not to prosecute her. Other aspects of the disparity between criminal prosecutions in eighteenth-century London and the activity are less obvious and must be pointed out explicitly. Also, criminal procedure during the seventeenth and early eighteenth century was not based on an adversarial system.ii As Thomas Green observes, the “accused . . . until late in the [eighteenth] century only occasionally had the advantage of counsel,” so Moll would not have been represented by an attorney, much less a team of them (270). The judge was supposed to represent the defendant’s interest by questioning witnesses brought against him or her. As Langbein points out, in most instances, and particularly in criminal trials at the Old Bailey, the prosecution would not have been represented by counsel either (“Criminal,” 282). Additionally, neither the defendant nor the prosecuting party articulated theories of cases (Langbein, “Shaping” 124). There were no opening statements or closing arguments. In fact, until almost the middle of the nineteenth century counsel was expressly “forbidden to ‘address the jury’” (Langbein, “Shaping” 129). I do not include a jury in the activity: only a judge. While a jury rather than a judge would have determined a defendant’s guilt or innocence during the eighteenth century, juries in London criminal trials generally rendered the verdict suggested by the judge, who, as Green asserts, left “little doubt of his own conclusions” (285). The absence of a jury, then, while historically inaccurate, would not likely have affected the outcome of most eighteenth-century trials.

The task of the activity’s prosecution team is broader in scope than the broker’s would have been in the trial depicted by Defoe. If all they had to do was prove Moll is guilty of stealing fabric, they would prevail every time since Moll admits she takes it (Defoe 214). Consequently, the prosecution team’s goal is to develop a theory of the case that presents Moll as a repeat offender who will continue to victimize innocent people if she reenters society. In actual eighteenth-century criminal trials, juries were more likely to convict a defendant of felony charges if they believed he or she was a repeat offender, even if the defendant had not been convicted of previous crimes (Langbein, “Criminal” 305). The novel also attests to this presumption. Moll believes she will be treated more harshly than one of her partners in crime if he is able to identify her because she is notorious in the criminal underworld for never getting caught (Defoe, 172).The defense team must excuse Moll’s criminal behavior while not attempting to deny that it occurred. They may request that Moll be convicted of a lesser crime not punishable by death. They might even imply the judge should ignore the evidence against Moll and find her not guilty. These strategies align surprisingly well with the only defenses ordinarily available to defendants during the eighteenth century. There are numerous historical precedents for the “yes, but” type of argument the defense is forced by Moll’s admission of guilt to adopt.iii As Langbein explains,

[o]nly a small fraction of eighteenth-century criminal trials were genuinely contested inquiries into guilt or innocence. In most cases the accused had been caught in the act or otherwise possessed no credible defense. To the extent that trial had a function in such cases beyond formalizing the inevitable conclusion of guilt, it was to decide the sanction. These trials were sentencing proceedings. The main object of the defense was to present the jury with a view of the circumstances of the crime and the offender that would motivate it to return a verdict within the privilege of clergy, in order to reduce the sanction from death to transportation, or to lower the offense from grand to petty larceny, which ordinarily reduced the sanction from transportation to whipping. (“Shaping” 41)iv

While it is difficult to procure a verdict of not guilty for Moll, the defense has a good chance at asking the judge to at least downvalue the goods Moll steals, a term meaning they would appraise the value of the goods she stole at less than its true worth in order to reclassify her crime as a nonfelony. This was a widely accepted practice although there was no legitimate legal precedent for it. As Langbein observes, juries sometimes even downvalued stolen sums of money, cases in which “downvaluing became transparent fiction” the purpose of which could only have been to prevent the defendant from hanging (Langbein, “Shaping” 54).

Lacking a viable argument for Moll’s innocence, the defense concentrates on mitigating circumstances and Moll’s character. Although these approaches had in theory no bearing on legal culpability, they were in fact the reason eighteenth-century juries downvalued most property crimes. Mitigating circumstances might include Moll’s poverty or her state of mind. As Dana Rabin notes, eighteenth-century defendants at trial “attributed their crimes to stress, drunkenness, and poverty— altered states of mind they hoped would earn the jury’s sympathy” (89). They emphasized their poverty in particular, characterizing it as a “force that overwhelmed their powers of self-restraint and compelled them to commit crimes” (Rabin, 93). Defoe’s novel provides ample evidence for this line of argument. Moll frequently justifies her thefts as the result of derangement induced by poverty. “Distress” takes away her “Strength to resist” (151). When “Poverty presses the Soul,” she asks rhetorically, “what can be done?” (151). Here and elsewhere in the novel she makes a sort of argument by analogy implying that her soul is being physically restrained, or pressed as she describes it, constraining her so that she cannot act according to her conscience. Students may take these statements by Moll and apply them more comprehensively to the effects of an indifferent and economically unequal society on Moll’s state of mind.

Another approach the defense can take is to produce character witnesses such as Moll’s pawnbroker friend to testify to Moll’s good qualities. As Green notes, this was a common occurrence in eighteenth-century trials (282). If a jury believed the accused was a decent person led astray by bad company or was only trying to support a family, they were more likely to downvalue stolen property. The defense team may also attempt to elicit sympathy from the judge on the basis of Moll’s sex, playing on gendered notions that women ought to be protected from hostile economic and social forces. As P. King argues, “[q]uantitative evidence indicates. . . that females were much more likely to be given partial verdicts,” meaning the jury would downvalue the goods they stole (255). The defense team can also fruitfully contextualize Moll’s crimes by focusing on her lack of opportunity in a society that treats women as property. In one memorable iteration of the trial the defense team used its closing argument to explain that if Moll had been able to go to business school and work in the corporate world she would have become a broker rather than a thief.

The trial activity takes four days of class if the class meets twice a week: two devoted to preparation and two to the trial. Although the preparation days obviously precede the trial days, I describe the trial first because preparations for it only make sense in the context of the trial. On both days of the trial the prosecution team sits together on one side of the classroom and the defense on the other. The first day of the trial begins with the opening statements, the prosecution team giving theirs first. I allow a maximum of five minutes for these opening statements, but the time allowed can vary depending on how many students are in the class. The opening statements should articulate each team’s theory of the case, meaning the strategy the teams will use to argue Moll should be executed, exonerated, or found guilty of a lesser charge. Then, each member of both teams presents evidence supporting the team’s theory of the case. Evidence for the purpose of this activity denotes an interpretation of a passage no longer than a paragraph from the novel. Each student stands in front of the class, reads relevant excerpts from his or her chosen passage, and explains in a maximum of two minutes how it contributes to the team’s assertions about Moll’s motives or character. This aspect of the trial trains students to select appropriate passages to prove arguments about texts and to articulate close readings that effectively support their contentions. It is is like writing an essay, except that it is delivered orally, written collectively, and intended to engage directly with another team’s counterarguments. The prosecution presents their evidence first, then the defense. While there are rarely more than a few minutes left in class after all the evidence is produced, students can use any available time to continue preparing for the second day.

On the second day of the trial both teams call and question witnesses to support their theories of the case. They also cross-examine the other team’s witnesses. Questioning and cross-examination are limited to five minutes per team per witness. A student from the team that called the witnesses must act as that witness. He or she sits in front of the class and answers truthfully according to Moll’s account in the novel any questions either team asks. While witnesses’ answers must not contradict the novel, they may interpret Moll’s motives and behavior in ways that are favorable to their team’s theory of the case. Witnesses who disappear or die over the course of the novel present from “beyond the grave.” All witnesses’ knowledge is limited to the episodes in which they participate or of which they have direct knowledge. Counsel is allowed to reveal to witnesses what happened to Moll later in her life and to ask them to provide their opinion of Moll’s actions. All witnesses have a copy of the novel with them to refer to specific passages during their testimony. Ideally, every witness plays a role in convincing the judge to render the verdict sought by his or her team. However, if a witness answers questions poorly or inaccurately, concedes aspects of the other team’s case during cross-examination, or becomes stubborn and defensive on the stand, then his or her testimony will benefit the opposing team. By playing and questioning witnesses, students develop skills such as thinking on their feet, recalling and recounting significant episodes of the novel, presenting in the most advantageous light a set of established facts (some of which are inevitably unfavorable to their team’s case), and acting in front of their classmates and professor. After all the witnesses have testified, the prosecution and then the defense deliver their closing arguments for up to ten minutes each. At the end of the trial the judge or judges render a verdict based on the totality of each team’s performance.

The two class sessions during which students prepare for the trial are as bustling with activity as Moll herself. Firstly and most importantly, both teams develop their theory of the case. Everything else follows from this decision. Their opening statements, closing arguments, choice of witnesses, and selection of evidentiary passages must align with their theory of the case in order for the team to prevail. Halfway through day one of preparation the teams take turns choosing witnesses. They cannot select the same ones so they need to prepare a list of alternate witnesses as well as their first choices. A coin toss determines which team chooses the first witness. Preparing effectively for the trial takes a lot of teamwork as well as thoughtful delegation of tasks to the right team members. Teams quickly learn that micromanaging everyone makes the project insurmountable. They must learn to play to team members’ strengths and trust each other to do a good job on assigned tasks. They usually end up striking this balance between assigning work to individuals and critiquing it collectively by using Google Docs. For example, one person might draft the opening statement and then the rest of the team would edit different portions of it on a shared Google document.

During the last two years I have brought in a mentor to help the teams use their preparation time wisely and avoid pitfalls such as presenting an overwrought theory of the case, choosing ineffective witnesses, or selecting inappropriate passages as evidence. These mentors can be graduate students or undergraduate students who took the course in the past and want to share their expertise. These mentors have improved the trials dramatically. They warn teams away from relying on limited or unconvincing theories of the case, help them select appropriate team members to play particular witnesses, and make them aware of strategies opposing counsel will likely use to rebut certain types of arguments. For example, one theory of the case that reappears every couple of years is the prosecution claiming that Moll is a sociopath or psychopath. Students find lists of symptoms of a sociopathic or psychopathic personality disorders on the internet or pick them up in an introductory psychology course and then try to apply them to Moll. This approach rarely works because even though the trial allows a great deal of latitude for anachronism, diagnosing Moll with a particular condition could just as easily mean that she should not be held responsible for her behavior as that she ought to be hanged for it. A mentor will help students avoid pitfalls like this.

Another aspect of the trial teams need the most guidance about is choosing team members to cast as witnesses. Witnesses should be quick-witted and comfortable in front of the class. They should also have read the novel carefully, especially if they play Moll or her pawnbroker friend. A sense of humor helps, too, since everyone enjoys the trial more when the people with the largest roles have fun. Occasionally teams select a member of their team to impersonate Moll or one of the other witnesses who becomes anxious or even paralyzed in front of the class. No matter how well a student knows the novel or how astute of a literary critic he or she is, that student must still be temperamentally suited to the pressure of being questioned and cross-examined in front of the entire class in order to make a good witness.

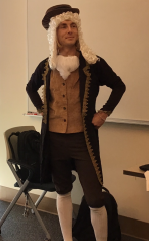

Figure 1 Student dressed up as Moll Flanders for Trial and Swearing to Tell the “Whole Truth and Nothing But the Truth” on Her Own Memoir

Photo credit: Miranda Kuehmichel

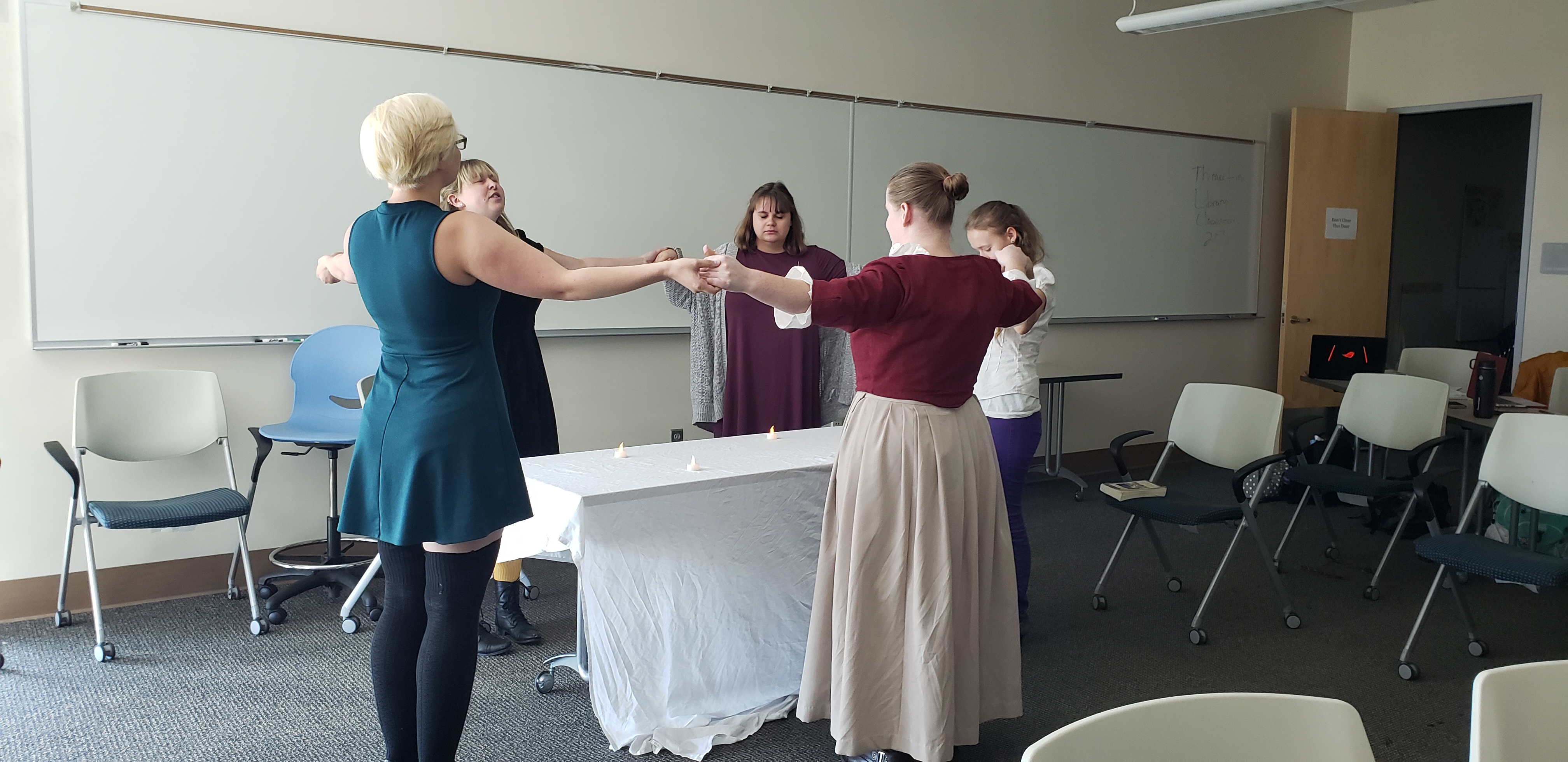

Figure 2 A Student Testifies as Moll’s “Married Friend” from Bath

Photo credit: Miranda Kuehmichel

Students enjoy this activity so much they will often do more than is asked of them. Last fall the students who portrayed Moll and Jemy wore costumes. Jemy frequently combed through his luxuriant wig with his fingers, a tic that conveyed his vanity and had the entire class laughing. This year a student playing the married friend from Bath wore tights, a vest, breeches, and a wig, and testified in an accent straight out of a Monty Python movie. Students often bring in food, particularly cakes. Last year one student brought in a cake decorated like Newgate, complete with a key just outside Moll’s reach. Another year a student decorated her cake with a paper doll version of Moll hanging from a noose. While this cake was macabre, its dark humor perfectly captured the tone of that year’s trial.

Sometimes students conspicuously and comically attempt to bribe me. Most memorably, a student playing the governess several years ago plied me with chocolate coins as she left the witness stand. A defense team several year ago scheduled a protest outside the classroom. Their friends yelled “free Moll” and carried signs opposing the bloody code. This year, the defense team staged a séance, complete with flickering electric candles, to raise Moll’s mother from the dead to testify.

Figure 3 Moll and the Defense Team Stage a Séance to Raise Moll’s Mother from the Dead to Testify

Photo credit: Miranda Kuehmichel

Some teams’ inventiveness runs in a more academic direction. For example, a defense team several years ago painstakingly constructed a document asserting Moll’s innocence that typographically resembled eighteenth-century pamphlets they replicated from ones they found using Eighteenth-Century Collections Online. They even dyed the paper with tea and crumpled it so that it looked historically accurate. A defense team several years ago commemorated their victory in the trial by giving me a gavel set I now use every year during the activity.

It would be easy to dismiss costumes, cakes, séances, and protests as gimmicky. However, they are part of what makes the trial special and memorable to each group of students. By doing these extra things students show they are invested in the activity. At least two-thirds of the students in my eighteenth-century novel course specifically refer in their course evaluations to the trial as something they enjoyed and that contributed to their understanding of eighteenth-century literature and culture. Years later, Boise State University alumni tell me the trial was one of their best memories of college. Some students have made lasting friendships working on the trial. It has been the most consistently successful learning activity I have used over the course of more than fifteen years of teaching eighteenth-century British literature.

Assessment

Students tend not to take seriously activities that are not assessed. They view such activities as “fillers,” something that professors use to pass the time when they do not want to lecture or facilitate discussion. Students must perceive the value of the Moll Flanders on Trial activity to make it successful. Consequently, I communicate how highly I value this activity by making it worth ten percent of students’ grades in the course. There are numerous ways you could allocate points based on this activity. I choose to emphasize individual performance because that is the only aspect of the trial students control. I reward teamwork as well but it constitutes only twenty percent of the overall grade for the activity. More importantly, teamwork is what results in a favorable final verdict, earning the winning team semester-long bragging rights. I allocate ten points for this activity on a hundred point scale: two for being present during all four days of the activity (one-half point off for every day missed); three based on the delivery of a close reading or an opening statement on the first day of the trial; three for acting as a witness, questioning and cross-examining witnesses, or delivering a closing argument; and two for being a productive and cooperative team member. I base the grade for evidence on the relevance of the passage the student selects to the team’s theory of the case, the quality and oral delivery of the close reading, and whether the student uses most of his or her allotted time. As for witnesses, they must know the novel well enough to answer questions quickly and accurately. Additionally, their answers should favor their team as much as possible. Questions posed by counsel should be clear and specific and produce answers that help prove the team’s theory of the case. Students’ contribution to their teams is more difficult to measure so I rely on their assessments of each other. They turn in a description of their own contribution on the last day of class. I also ask them how their group worked together and whether all team members contributed significantly to the trial. Most of these assessments are positive. However, if similar criticisms of the same team member appear in at least two assessments then I talk to that student and determine whether the concerns expressed by their teammates are accurate. Usually, just knowing peers will evaluate you provides sufficient incentive for students to perform well.

Rendering Judgment

One of the most challenging aspects of this activity from a teacher’s point of view is not how to grade it, but how to render a verdict. There are three possibilities for a verdict. I can find Moll guilty of the felony of grand larceny, a crime that carries the penalty of execution. I can also downvalue the goods she steals and find her guilty of a lesser crime penalized by whipping or transportation to the colonies. If the defense does an excellent job with their character witnesses or by excusing Moll’s crimes I sometimes even exonerate Moll. Although I do not allocate any points for prevailing in the trial, students feel passionately about winning. The desire to beat the other team is often more motivating for them than the grade they receive. I have developed an informal system that assists me in determining which team performed best and in explaining my decision to both teams. I assign four points based on each team’s overall performance in the trial: one based on the strongest opening statement; one for the team that produces the overall best evidence, one for the team that has the best performances and questions during the witness portion of the trial; and one for the best closing argument. If the teams are tied then I give an extra point for the team whose performance is most imaginative or does things that make the trial fun and engaging. This is where costumes or cakes can tip the scale. What I’m looking for in a tiebreaker is the team that cares the most about the activity. I generally explain my reasoning for my decision briefly after I render verdict, making sure to acknowledge at the same time great performances on both teams.

Conclusion

Moll Flanders on Trial hones students’ ability to interpret literary texts and justify larger arguments based on close readings. Students must develop a collective thesis (their theory of the case), explain this thesis clearly in speech in front of the class, select and explain the relevance of the most effective evidence to support their thesis, and defend their thesis by eliciting favorable answers from witnesses. Their grades depend on their success at achieving these goals, and the trial’s outcome is based on how well the teams as a whole do so. It is pedagogically effective and a lot of fun. Additionally, this activity is flexible enough that it can be adapted to work for almost any novel with a trial in it. It can even work for some novels that are based on a sort of test, even if that test does not culminate in a trial. I have used versions of it when teaching Frankenstein and even Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. (I staged a trial of Gawain by Arthur’s court for violating the code of chivalry.) One of my colleagues uses a trial modeled on Moll Flanders on Trial when he teaches The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in an online course. I almost always have students who major in English education in my eighteenth-century novel course, and I encourage them to use some version of the trial in their own future classes. Many of them have done so and have let me know how it worked. They have staged trials in junior high and high school classrooms when teaching texts as different as The Great Gatsby and The Hunger Games. This activity is obviously useful to students and it also helps me increase enrollment in my eighteenth-century novel courses. I enjoy this activity every year and hope you will find some version of it useful in your courses as well.

Boise State University

i I describe another learning activity I frequently use in eighteenth-century courses in an earlier article, “Embodying Gender and Class in Public Spaces through an Active Learning Activity: ‘Out and About in the Eighteenth Century.”

ii As Langbein notes, several aspects of criminal procedure we would consider foundational were not present in the eighteenth century. These include the “the law of evidence, the adversary system, the privilege against self-incrimination, and the main ground rules for the relationship of judge and jury” (“Shaping” 2).

iii See J. M. Beattie, 251-2.

iv The benefit of clergy derived from the medieval distinction between secular and ecclesiastical courts, with members of the clergy being held to account for criminal offenses only by their own courts. It had changed so much by Defoe’s time it bore little resemblance to its medieval antecedent. It allowed first-time offenders of lesser felonies to escape capital punishment in favor of a lesser sentence such as transportation or hard labor.

WORKS CITED

Beattie, J. M. “London Juries in the 1690s.” Twelve Good Men and True: The Criminal Trial Jury in England, 1200-1800. Edited by J. S. Cockburn and Thomas A. Green, Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 214-253.

Campbell, Ann. “Embodying Gender and Class in Public Spaces Through an Active Learning Activity: ‘Out and About in the Eighteenth Century.’” ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830, vol. 7, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-7.

Davidson, Cathy. The New Education: How to Revolutionize and University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux. Basic Books, 2017.

Defoe, Daniel. Moll Flanders. Edited by Albert J. Rivero, WW. Norton, 2004.

Green, Thomas Andrew. Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury, 1200-1800. University of Chicago Press, 1985.

King, P. J. R. ‘Illiterate Plebians, Easily Misled’: Jury Composition, Experience, and Behavior in Essex, 1735-1815.” Twelve Good Men and True: The Criminal Trial Jury in England, 1200-1800. Edited by J. S. Cockburn and Thomas A. Green, Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 254-304.

Langbein, John H. “The Criminal Trial Before the Lawyers.” University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 45, no. 2, 1978, pp. 263-316.

—. “Shaping the Eighteenth-Century Criminal Trial: A View from the Ryder Sources.” University of Chicago Law Review, vol. 50, no. 1, 1983, pp. 1-136.

Rabin, Dana Y. “Searching for the Self in the Eighteenth-Century English Criminal Trials, 1730-1800.” Eighteenth-Century Life, vol. 27, no. 1, 2003, pp. 85-106.

Showalter, English Jr. The Stranger: Humanity and the Absurd. Twayne Publishers, 1989.