Remediating the “Female Pyrates”

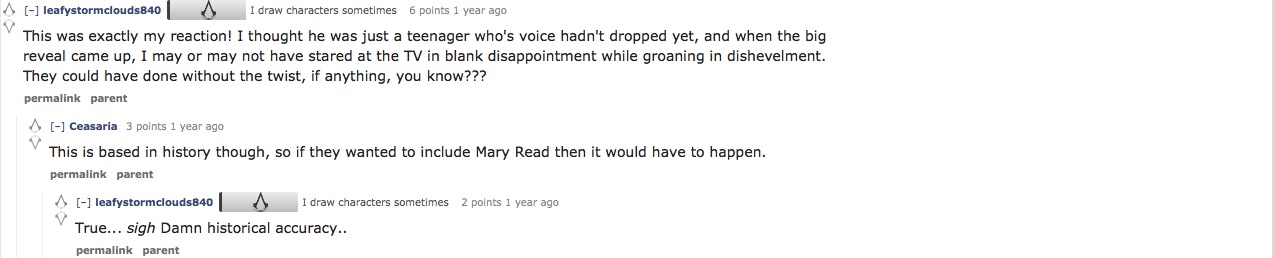

A game devoted to the representation of piracy as the subject of popular entertainment in the eighteenth century would have to include those contemporaneously famous figures that Johnson’s own History billed on its title page above every single ship’s captain, including their own (fig. 4). The layout indicates that the actions and adventures of the female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read are even more “remarkable” than those of the men below; though literally “contain’d” in the chapter on Jack Rackham, under whose flag they sailed, their names and stories have in another sense escaped containment and threatened to disrupt the social and sexual hierarchies of the day. The challenge they posed to normative gender roles in eighteenth-century Europe have twenty-first century corollaries; to encounter Bonny and Read within the historical simulation is to confront the presence of transgressive women in not one but two spaces conventionally viewed as ‘masculine’ or male-dominated: the worlds of eighteenth-century piracy and twenty-first century “hardcore” video game culture.[1] While that simultaneousness introduces a potentially problematic presentism that jeopardizes the perception of that phenomenon as historically accurate, it also re-contextualizes and therefore recreates some degree of the sense and sensationalism of the phenomenon in its original time.

Fig. 4: Title Page, A General History of the Pyrates, 2nd ed. (1724). Smithsonian Library, 39088002097426.

Whereas pirates with hooks for hands and parrots for companionship have maintained near-iconic (albeit comic or operatic) status despite a relative lack of historical precedent, representations of Bonny and Read (or characters like them) have experienced precisely the opposite. Their stories, as Diane Dugaw writes, “continued to be popular reading fare well into the nineteenth century” as part of a larger preoccupation with lower-class “gender disguising heroines” (183). Their place in popular culture, though, has since dwindled, especially in comparison to their male counterparts — even those who owe their apparent immortality almost entirely to fiction. While “their cross-dressing adventures were not as unusual among early modern women as previously believed,” Rediker adds, “many modern readers must have doubted them, thinking them descriptions of the impossible” (Villains 166). To those members of the hardcore gaming community most likely to have had their first encounters with Bonny and Read through this medium, and even more so to those gamers whose gender and perspective are already in alignment with those of Edward Kenway, it therefore seems likely that ACIV’s representation of what Rediker calls “not the typical, but the strongest side of popular womanhood” in the early eighteenth century would appear improbably modern (Villains 174) — a sociopolitical anachronism rather than an historicized representation of phenomena separated from the world as they know it by three hundred years of patriarchal dominance, to say nothing of the continuing influence of entrenched dynamics in video game culture and the distortions of the Disney industrial complex.[2]

At first gaze, the game would seem to support that perspective by wrapping its female pirates in the trappings of modern marketing strategies that heighten their conventional sexuality at the expense of the destabilizing power of gender amorphousness. In comparison to their depiction in Johnson’s text, for example, Ubisoft presents a physically slighter, more “feminine” Read and an overtly sexualized Bonny (figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 5: Anne Bonny and Mary Read. A General History (1724). © The British Library Board. C.121.b.24.

While such modeling reflects trends within the industry, it also reflects the popular fate of Bonny and Read in the eighteenth century.[3] In 1725, Hermanus Uytwerf published a Dutch edition of A General History featuring a different interpretation of the by-then already famous female pirates (fig. 7). The engravings in Historie der Englesche zee-roovers (1725) display both women with wilder hair, smaller noses, thinner faces, narrower trousers, and — most unambiguously — exposed breasts. Ubisoft’s Bonny and Read, then, are not necessarily more sexualized than were Johnson’s.[4]

Fig. 7: Anne Bonny and Mary Read. Historie der Engelsche zee-roovers (1725) © The British Library Board. 9555.aaa.1.

Their remediation of the female pirates as portrayed in these works creates the possibility of an historical experience the authenticity of which derives in part from its playing out again in a new social context. Sally O’Driscoll offers an overview of the engravings’ original significance:

The swift visual repackaging of Bonny and Read can be read as a process of sexualization, part of the cultural work that made Bonny and Read into glamorous, notorious, and malleable figures used to reframe and normalize excessive or problematic female behavior. But it can also be read as the sign of an emerging fascination with the female body qua body — a fascination that is accompanied by a detailed rhetoric of investigation. The eighteenth century’s concern with the female body is made manifest through a willingness to interrogate the material reality of the female body, its uses and functions, its social meaning. The pirates’ breasts are not simply a sign of their femaleness: they are a clue to the nature of womanhood itself (a concept that changed drastically during the course of the eighteenth century), an ambiguous signifier of what women are or should be — and a reminder of how far these particular women have strayed from the ideal. And in yet another layer of meaning, the pirates’ breasts offer pleasure: the narrative frames them in such a way that the audience can enjoy them — we are given permission to commodify and consume the images of female bodies displayed for our amusement (359-60).

The issues raised by Johnson’s history and the visual repackaging of Bonny and Read in the eighteenth century are raised again by the remediation of that repackaging in the twenty-first. The social meaning of the female body remains fraught, particularly in a world notorious for the often exaggerated proportions and misogynistic treatment of its female characters but which is increasingly becoming a contested space as player demographics and demands continue to shift — promising (or, to some minds, threatening) to destabilize the established social order of core game subculture and stereotypical notions of what women can, are, or should be within it.

Ubisoft’s simulation reproduces a version of the two histories’ intertextual dynamic entirely within itself. The bodies of Read and Bonny are not as interchangeable in the game as they appear in the engravings, which differ greatly across the texts but not across the images within them. Unlike the Bonny of Johnson’s text, for example, ACIV’s Bonny never cross-dresses; the game thus foregoes the possibility of her passing as male. The game here seemingly follows Uytwerf’s translation in superficially eradicating what O’Driscoll calls the “frisson of ambiguity” surrounding the women in Johnson’s original (359). Indeed, Kenway first encounters Bonny serving drinks to and staving off the advances of a drunken Rackham; players thus immediately see her in a stereotypically gendered role and wearing revealing attire while under the implied sexual threat of a man. Kenway’s very presence in the scene furthermore suggests, albeit obliquely, his greater suitability as a match and by extension the possibility of her eventual normalizing domestication.

Almost as immediately, however, the scene restores a degree of gender instability. When Rackham grabs her by the arm and asks, “dear lady, what do they call you?” Bonny responds, “Anne when they’re sober, a jilt when they’re sauced, but never ‘lady.’” She rejects the epithet as well as the man who would impose it upon her, and though Kenway sits within blade’s reach, she gives no indication that his intervention is wanted or necessary. As she pulls away from Rackham, he simply spills out of his chair and onto the floor in inebriated impotence. Despite her circumstances and appearance, Bonny neither sees herself nor allows the player to see her as a damsel in distress.

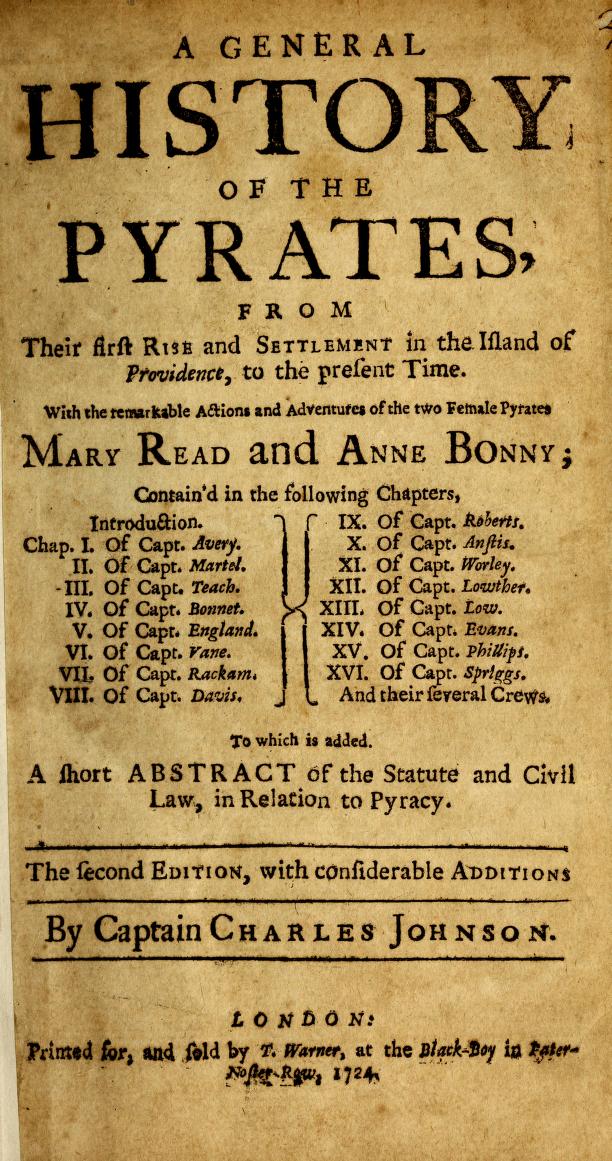

The game’s characterization of Read, meanwhile, amplifies the frisson of ambiguity beyond even what Johnson achieved. Whereas A General History boldly advertised the names and narratives of both its female pirates, ACIV conceals those of Mary Read until the fifth of 12 memory sequences. Kenway knows Read only as “James Kidd,” the illegitimate son of William Kidd. They fight in tandem (Read is also an Assassin), and at no point before she reveals her identity does any character hint at having had doubts. Johnson insists the same held true amongst her actual shipmates.[5] More importantly, messages posted by players to online forums reveal that Read also passed as Kidd beyond the diegesis. A post in an Assassin’s Creed subreddit, for instance, asks if anyone else “found James Kidd attractive,” and while many of the 83 responses insist that Kidd’s “feminine voice” and “feminine features” revealed the truth immediately, others “just assumed that he was a physically underdeveloped guy” or “a teenager whose voice hadn’t developed yet.” One player wrote, “when I first heard Kidd speak, I remember thinking that the voice actor sounded quite feminine, but I didn’t even consider that the character might be female…Since I was so busy pondering the gender of the voice actor (rather than the character), the twist caught me by surprise” (“Did Anybody Else…?”). In this case, the ambiguity transcends the game and the historical world it simulates to trouble issues of gender in the “real” world and the making of the game itself.

Together, Ubisoft’s Bonny and Read collapse the conceptual distance between the representation of women in the game and the representation of women in gaming — a collapse facilitated by a metanarrative that refashions the Animus into a game console. If recognized, then this alignment allows players to experience the significance of the female pirates as immediately rather than only historically relevant, just as readers might have in 1725. If players have misidentified the characters as “impossible” anachronisms, then that immediacy becomes all the more poignant, as implied by this brief exchange within the same subreddit thread (fig. 8):

The first poster’s grudging acknowledgement that “historical accuracy” legitimizes the reveal of Read’s gender indicates an initially strong and negative presentist experience, whatever its exact substance or significations. Of course, players also remain free — again, just as readers did in 1725 — to enjoy Read and Bonny as female bodies displayed for pleasure and amusement. Comments on the attractiveness of Bonny, Read, and Kidd unsurprisingly pepper the message boards along with occasional and perhaps only tenuously ironic addenda about players questioning their own sexuality and finding reassurance in the reveal.

That interpretive freedom, though necessary to the remediation of eighteenth-century literary and graphical encounters with the female pirates, entails the risk of endorsing or perpetuating stereotypes that diminish their transgressive potential. If on the one hand the script allows Bonny, who vanishes from the historical record after pleading her belly to the authorities in Kingston, to escape and serve as Kenway’s quartermaster, then on the other hand it dresses up the record of Read’s death in a Jamaican jail with a shift, stays, and dark red lip coloring. Both women do at a critical moment become the damsels in distress they initially refused to be, and of the two, only the less sartorially and sexually disruptive gets to live.

These reversals would seem to authorize a final reading of the female pirates as “safely” domesticated. “Yet, the narrative,” as O’Driscoll writes of A General History, “cannot convince the reader of this interpretation because it undercuts itself; Read’s pirate comrades claim that she loved being a pirate, and quote her saying she would never give it up. Read dies at the end…and so does not have the chance to choose an ending that would foreclose the ambiguity of her tale” (364). The same holds true for the Read and Bonny of ACIV. Read’s last words promise Kenway that she will always be with him, but they immediately follow her challenging him to do his part for the Assassin Order as she has done hers; it is unclear to which she is the more devoted. Bonny, meanwhile, finally refuses Kenway’s invitation to return with him to England as well as the possibility of remaining with the Assassins herself. The game, then, may impose upon Bonny the outward trappings of conventional femininity and leave Read to die in Kenway’s arms, but the story does not in itself reduce them to simplistic gender stereotypes. As in A General History, their meaning remains ambiguous, and in Ubisoft’s remediation they not only retain but also gain new power to destabilize.

NOTES

[1] Steven E. Jones notes “the homosocial ethos of much of hardcore gaming” and an industry logic that in general “sees hardcore gamers as gendered ‘masculine.’” In contrast to hardcore gamers, “casual gamers” are those “interested in fun, including women in particular” (142-45). Neither demographic is monolithic. See also Melissa Terlecki, et al., “Sex Differences and Similarities in Video Game Experience, Preferences, and Self-Efficacy: Implications for the Gaming Industry”; Adrienne Shaw, “What is Video Game Culture? Cultural Studies and Game Studies”; and Justine Cassell and Henry Jenkins, From Barbie to Mortal Kombat: Gender and Computer Games.

[2] The Pirates of the Caribbean movies have in the last ten years featured four female pirates: Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Swann, Zoe Saldana as Anamaria (The Curse of the Black Pearl and Dead Man’s Chest), Takayo Fischer as Mistress Ching (At World’s End), and Penélope Cruz as Angelica (On Stranger Tides). Of the four, only Mistress Ching represents an identified historical personage; Ching Shih (1775-1844) led a large and organized force in the South China Sea. The other three do don traditionally masculine attire, but the films do not establish any of them as cross-dressing with the intent to pass as men.

[3] “Content analyses of video games and video game advertisements have consistently found that women are underrepresented, more frequently sexualized, more attractive, less powerful, and dressed more scantily than males” (Miller and Summers 735). See also B. Beasley and T. Collins Standley, “Shirts vs. skins: Clothing as an indicator of gender role stereotyping in video games.”

[4] This in no way means that the game does not perpetuate potentially harmful stereotypes of and attitudes toward women; nor does its winking self-reflexivity necessarily absolve Ubisoft for following in the wake of Uytwerf’s Zee-Roovers when history offered an alternative.

[5] “Her Sex,” Johnson writes, “was not so much as suspected by any Person on Board till Anne Bonny, who was not altogether so reserved in point of Chastity, took a particular liking to her,” at which point Read revealed herself to Bonny to “explain her own Incapacity that way” (162).