ELIZA HAYWOOD’S A Spy Upon the Conjurer: A Collection of Surprising Stories, with Names, Places, and particular Circumstances relating to Mr. Duncan Campbell, commonly known by the Name of the Deaf and Dumb Man; and the astonishing Penetration and Event of his Predictions (1724) is an epistolary text about Duncan Campbell, the famous “deaf and dumb” fortune-teller who lived and worked in London in the early eighteenth century.i The text’s fictional narrator, Justicia, says that she wants to convince her reader, an unnamed lord and friend of hers, that the real-life Campbell is legitimate—that he is not a fraud. The few scholars who have studied A Spy Upon the Conjurer have interpreted it as a hack publicity piece meant to support Campbell’s business and reputation, also suggesting that Haywood herself believed in Campbell as a fortune-teller who had second sight.ii As Felicity Nussbaum puts it, “Haywood’s attitude [towards Campbell] is largely one of respect, admiration, and celebration” (Limits 51). However, while Haywood’s narrator clearly admires Campbell, numerous rhetorical and narrative elements of the text suggest a distance between Haywood as author and Justicia as narrator—a distance that creates tension between Justicia’s claims about Campbell and what Haywood seems to suggest the reader should, in the end, believe about him. This tension invites readers to be skeptical of Justicia, a fictional, first-person narrator who fails to meet standard conventions of reliability, and this invitation ultimately shifts authority away from the dubious narrator onto the reader. This shift foregrounds problems of judgment by enlisting the reader to determine truth even as the text, which undermines the trustworthiness of both sensory perception and testimony, creates skepticism about one’s ability to do so. Critics have recognized the ambiguity and skepticism of supernatural narratives written by other writers such as Daniel Defoe; however, they have not recognized the same qualities in A Spy Upon the Conjurer.iii Nevertheless, attention to the text’s narrative authority (or lack thereof) and its portrayal of failed empiricism reveals that it moves beyond an apology for Campbell and, in fact, challenges the credulity upon which such a defense would depend. With this argument, I do not mean to deny that Haywood intended to use her narrative to make money by publicizing Duncan Campbell; as Patrick Spedding notes, there is evidence that Campbell may have sold copies from his house and even loaned them out to promote his reputation (141). However, such facts do not necessarily imply that Haywood believed in him, and, in fact, many aspects of the text suggest that perhaps she did not.

In this fictional narrative, Haywood uses Campbell as a case study to signify the limits of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century empiricism, which John Waller characterizes as “‘sensible evidence’ provided by credible witnesses” (24). Although members of the Royal Society who championed empiricism claimed to take an objective, skeptical approach to science, they were also concerned about the dangers of extreme skepticism that they thought might threaten not only natural philosophy but also religious belief and various types of knowledge making, including history. As a result, they, at times, defended credulous positions and attacked skeptical ones, especially regarding supernatural or preternatural concerns, such as witchcraft, apparitions, and second sight (Waller 30, Shapin 244). Haywood’s text about Campbell and his second sight challenges and even satirizes anti-skeptical writers, such as Joseph Glanvill, Richard Baxter, and, especially, William Bond, writers who privileged credulity over skepticism in their attempts preserve the legitimacy of empiricism and testimony. A Spy Upon the Conjurer’s response to these credulous texts places it firmly in the skeptical tradition of the Enlightenment—a tradition from which Haywood is typically excluded—and it shows that rather than being a straightforward advertisement for Campbell, Haywood’s text is a genre-bending work that satirizes anti-skeptical narratives while offering a significant contribution to eighteenth-century fictionality. Although Haywood’s skepticism might not reflect the extreme philosophical skepticism that rejects one’s ability to know anything at all, she does demonstrate extreme anxiety about the difficulty of determining truth as well as the real-life consequences of the failure to do. As a result, in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, she engages with and challenges traditional systems of knowledge making, and she migrates conventional epistemological questions and problems from male-centered dialogue about science and God to the realm of individuals’, and especially women’s, daily lives and relationships.

Haywood generally has not been included in studies about skeptical writers of the eighteenth century. In fact, such studies have focused primarily on male writers. Seminal studies by Michael McKeon, Eve Tavor Bannet, Fred Parker, and James Noggle, for example, focus on male writers. Some exceptions include books by William Donoghue, Christian Thorne, and Sarah Tindall Kareem, which include discussions of women writers. However, Donoghue’s study of skepticism and fiction does not mention Haywood, despite having a chapter titled, “Skepticism, Sensibility, and the Novel.” In Thorne’s study of skepticism in the Enlightenment, he gives significant attention to Aphra Behn’s drama but only briefly mentions women novelists. His discussion of Haywood (which spans just a couple of pages) characterizes her, along with Behn and Jane Barker, as an author of “anti-romances,” which he frames as “love stories that never get off the ground” and that “are the death-rattle of an aristocratic culture of courtly love” (270).iv Rather, it is Defoe’s Roxana, Godwin’s Caleb Williams, and Sterne’s Tristram Shandy that receive the bulk of Thorne’s attention in his chapter called “Skepticism and the Novel.” More recently, Kareem, in Eighteenth-Century Fiction and the Reinvention of Wonder, has included Jane Austen and Mary Shelley alongside male writers such as Defoe, Hume, Fielding, Walpole, and Raspe, but Haywood goes unmentioned.

When skepticism in Haywood’s work is neglected, important elements of her texts are overlooked. In fact, King states in the epilogue to her political biography on Haywood that

insufficient attention has been paid to Haywood’s representation of lies, secrecy and hidden lives and to her imaginative attention to a cluster of Enlightenment themes: skepticism, credulity, collective delusion on the part of an easily infatuated public, the power of print to represent and misrepresent. (198)

Earla Wilputte is one of a few critics who have examined skepticism in Haywood’s work, especially in texts such as The Adventures of Eovaai (1736) and Dalinda; or The Double Marriage (1749).v However, Wilputte states that Haywood’s skepticism does not begin until the 1740’s with The Female Spectator (1744-1746), arguing that it develops in response to nine months of “broad-bottom” government (“‘Too ticklish’” 136). In contrast, I suggest that Haywood’s skepticism starts much earlier and that, with A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood is demonstrating a skeptical aesthetic and also engaging with the broader intellectual culture of the early eighteenth century.

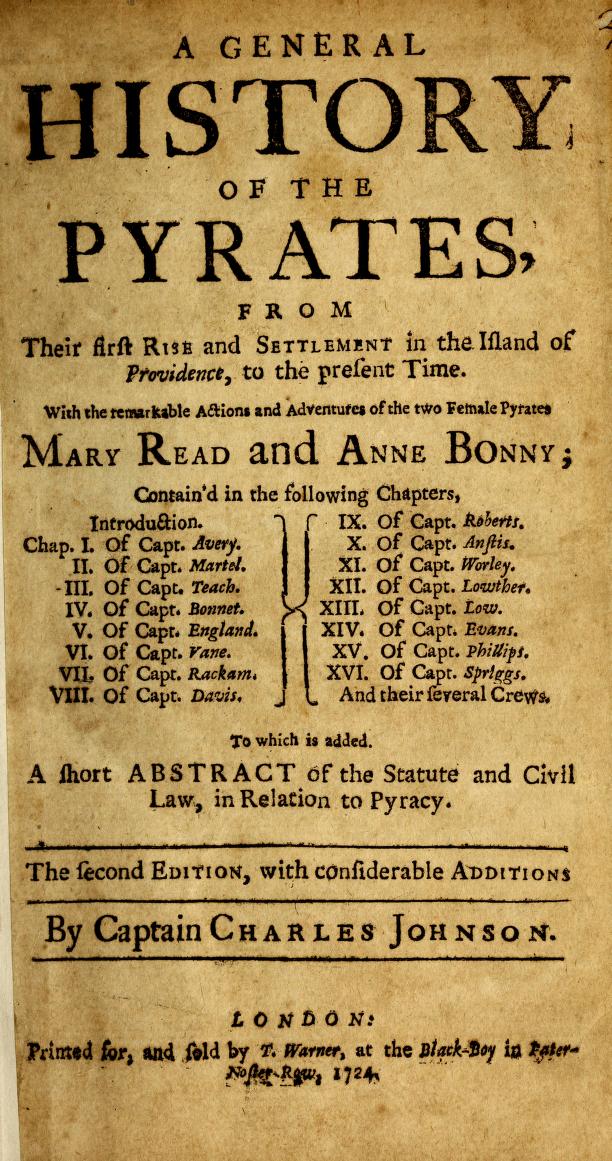

Haywood’s book about Campbell is in direct conversation with the first book written about him, which was published in 1720 and written by William Bond (although it was formerly attributed to Defoe and, even as late as 2005, to Haywood).vi Bond also co-wrote The Plain Dealer with Aaron Hill, and, with Martha Fowke Sansom, who was part of Aaron Hill’s coterie, Bond co-wrote The Epistles of Clio and Strephon (1720) and The Epistles and Poems of Clio and Strephon (1729). In addition, Sansom wrote verses to Duncan Campbell that Bond included in the introduction to his “history” of the fortune-teller. This means that Bond likely would have had contact with Haywood through Sansom or Hill around 1720. However, by the time Haywood published her narrative about Duncan Campbell, she was estranged from the Hillarian Circle. To some degree, this timeline should lead us to consider more carefully implications or claims that, when Haywood published A Spy Upon the Conjurer, she and Campbell, not to mention she and Bond, were part of the same “literary set.”vii

Bond’s The History of the Life and Adventures of Mr. Duncan Campbell serves as a biography of sorts, as well as an apology, for Campbell. Within the limited scholarship on the relationship between Bond’s and Haywood’s texts, Rebecca Bullard contrasts them, but rather than focusing on the tension between credulity and skepticism, she studies the texts’ different approaches to curiosity (171). Jason S. Farr considers the two texts together as part of what he calls “the Duncan Campbell Compendium,” but he focuses on the portrayal of deafness as natural and normal, commenting little on how either text features debates about credulity and skepticism, and he ultimately argues that Haywood builds on Bond’s earlier work and thinks her readers would be “enlightened” by it (72). Farr does not explore how Haywood’s text challenges Bond’s, and in terms of Campbell’s status and legitimacy, Farr does not make a clear distinction between the attitudes of the author (Haywood) and those of the narrator (Justicia).

Riccardo Capoferro does address skepticism in his discussion of Bond’s and Haywood’s texts, and he recognizes that, like apparition narratives, their texts “bridge the gap between empiricism and the beliefs it implicitly calls into question” (140). He also admits that A Spy Upon the Conjurer offers a “developed example of ontological hesitation,” but, oddly, he argues that it does not “directly engage with epistemological problems” but rather “presents itself as a form of pure entertainment.” He writes,

In most of these anecdotes, Duncan’s powers are described as a source of uncertainty for his customers, although they are ultimately verified. A shift from hesitation to certainty also informs the first chapter, in which the narrator herself stages her first encounter with Duncan.

Capoferro’s brief discussion of Haywood’s text ignores the ongoing challenges to Campbell’s legitimacy that thread throughout the work. He also conflates the narrator with the author and neglects to note Justicia’s questionable reliability or the fact that her designated reader, the unnamed lord, is a skeptic who doubts Campbell’s powers and who does not believe in the supernatural. Essentially, Capoferro overlooks or dismisses the “epistemological problems” that dominate A Spy Upon the Conjurer.

In texts about Campbell, epistemological questions about his second sight are compounded by his claims of deafness. Not only does Campbell claim to have knowledge that others with all five senses do not, but even his deafness cannot be proven through empirical methods such as “ocular demonstration” or experimentation. Among his contemporaries in London society, skeptics doubted not only whether he had second sight, but also whether he was actually deaf—neither of which they found easy to prove true or false. In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Justicia recounts stories about people who tested Campbell’s deafness and muteness by performing tricks and “jests.” For example, Justicia recounts tales of doctors who mistreated Campbell in order to get a verbal reaction, assailants who attacked him in bars just to provoke him to speak, and a woman who smashed his fingers in a door in an effort to elicit cries of pain (140-150).viii

Debates about Campbell’s deafness have continued even into the twenty-first century. Nussbaum finds the evidence “compelling that Campbell was truly hearing-impaired though he may have had a modicum of hearing” (Limits 45), while Lennard J. Davis calls Campbell a “huckster who only pretended to be deaf and who made his money by duping people” (176n32). R. Conrad and Barbara C. Weiskrantz argue that Campbell could not have been totally deaf, despite stories that he never spoke—not even when he was drunk. Commenting on the memoir that Campbell allegedly wrote, they say,

It is hard to believe from the language that they are the unedited writing of a congenitally deaf man. Rather, they suggest a naïf or a charlatan. The memoirs contain no reference at all to deafness, but consists [sic] of a collection of essays on occult phenomena, together with testimonial letters from admirers. (329)

Conrad and Weiskrantz also point out that Campbell is said to have played the violin and to have tuned it “by putting the neck of the violin between his teeth,” which they say suggests that he possessed “bone conduction of sound” (329). Finally, they refer to him as the “despised Campbell” and claim that Campbell, despite his fame, inspired ridicule among his contemporaries. Certainly, Campbell was (and still is) a subject of debate. For my argument, however, what matters most is not whether Campbell was truly deaf, but rather the debate itself—and how A Spy Upon the Conjurer presents Campbell as a signifier for a variety of epistemological questions that seem impossible to answer.

Bond addresses many such epistemological questions in his history of Campbell, including not only questions about Campbell’s deafness and second sight, but also general questions related to apparitions, witchcraft, and other supernatural or preternatural mysteries. In fact, after a dedicatory epistle and the introductory verses by Sansom, Bond’s text begins with a story called “A Remarkable Passage of an Apparition. 1665.” Although the apparition story, which does not feature Campbell, might seem irrelevant to the history, for Bond, any story affirming the legitimacy of supernatural or preternatural events is support for his defense of Campbell. In Origins of the English Novel: 1600-1740, McKeon specifically addresses the kind of supernatural episodes or “apparition narratives” that are included in and, in many ways, constitute Bond’s text, placing them firmly within the tensions that existed in the early eighteenth century between optimistic empiricism and more dubious skepticism that called all knowledge into question (83-89). The legitimacy of these apparition narratives relied heavily on the credibility of the original sources of the perceived experiences. In other words, the reliability of the tales greatly depended on who was doing the telling. Glanvill, writing about witchcraft in 1681, observes, “Now the credit of matters of Fact depends much upon the Relatours, who, if they cannot be deceived themselves nor supposed any ways interested to impose upon others, ought to be credited” (qtd. in McKeon 85). As a result of this dependency on the “relatours,” such narratives focus heavily on the authority and credibility of those who tell the stories about apparitions, genies, and witches. However, Glanvill is also claiming that, if there is no obvious reason to discredit the “Relatour,” then he ought to be trusted. As Steven Shapin points out, members of the early Royal Society sought “a golden mean between radical skepticism and naïve credulity” but they were “marginally more worried by illegitimate skepticism than by illegitimate credulity” (244). In general, Shapin says, gentleman were to be trusted unless they gave good reason not to be, and as Barbara Shapiro notes, until the eighteenth century, testimony of reliable witnesses was considered a form of superior evidence (28). Writers of these narratives therefore employed common conventions to establish credibility and fend off skeptics. As Jayne Elizabeth Lewis puts it, “In the interest of compelling readerly belief, apparition narratives made conscious efforts to verify the good character of living witnesses to the phenomena they described” (88).

Apparition narratives were still “ubiquitous in the 1720s” (Lewis 86), and Bond signals his text’s connection to this anti-skeptical tradition by incorporating apparition stories from Glanvill as well as Baxter, the latter of whom also wrote anti-skeptical texts, including one with the anti-skeptical (and formidable) title, The Certainty of the Worlds of Spirits and, Consequently, of the Immortality of Souls of the Malice and Misery of the Devils and the Damned : and of the Blessedness of the Justified, Fully Evinced by the Unquestionable Histories of Apparitions, Operations, Witchcrafts, Voices &c. / Written, as an Addition to Many Other Treatises for the Conviction of Sadduces and Infidels (1691). Like Glanvill and Baxter, Bond challenges the incredulous “free-thinkers” who doubt supernatural reports, suggesting they have no reason for skepticism other than their own native incredulity (80).ix He also uses rhetoric like Glanvill’s and Baxter’s to suggest that skepticism of reputable sources potentially undermines all knowledge. Anticipating naysayers who reject testimony about supernatural experiences, Bond writes, “In a word, if People will be led by Suspicions and remote Possibilities of Fraud and Contrivance of such Men, all Historical Truth shall be ended, when it consists not with a Man’s private Humour or Prejudice to admit it” (106). Bond’s text characterizes skepticism as a flawed personal disposition that threatens the collective enterprises of knowledge making and religious belief.

To establish his own credibility and support his claims about Campbell and other preternatural phenomena, Bond’s narrator regularly invokes the empirical evidence of sensory perception, as when, after his first apparition narrative, he writes,

These Things are true, and I know them to be so with as much certainty as Eyes and Ears can give me, and until I can be perswaded [sic] that my Senses do deceive me about their proper object and by that perswasion deprive my self of the strongest Inducement to believe the Christian Religion, I must as will assert, that these Things in this Paper are true. (31)

Throughout the text he cites case after case in which people have seen and heard—with “Eyes and Ears”—various spirits and apparitions. Bond’s emphasis on the reliability of his senses reflects a foundation of empiricism, but in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, there were also doubts about how trustworthy our senses really are. For example, even Robert Hooke, the curator of experiments for the Royal Society doubted the reliability of our natural, unaided senses. In the preface to Micrographia (1665), he expresses concern about the limitations of the senses, and he emphasizes the power of instruments—telescopes, microscopes, and other lenses—to rectify sensory failings. Margaret Cavendish challenged overreliance on the senses (as well as the use of instruments to enhance them), arguing that eyes and ears cannot show the “interior motions” of nature and its animals and objects, whether aided or not, and thus yield no “advantage” to man. She writes that “man is apt to judge according to what he, by his senses, perceives of the exterior parts of corporeal actions of objects, and not by their interior difference; and nature’s variety is beyond man’s sensitive perception” (115). Bond’s narrator, however, relies heavily on the trustworthiness of sensory perception in his defense of Campbell.

To enhance the credibility of his sensory evidence, Bond’s narrator, like those of apparition narratives, focuses on the sources of his evidence and tales, citing such specific and notable cases as those related by presumably authoritative and trustworthy relators, such as Socrates, Aristotle, King James, John Donne, and the Italian poet Tasso:

Men, who will not believe such Things as these, so well attested to us, and given us by such Authorities, because they did not see them themselves, nor any Thing of the like Nature, ought not only to deny the Demon of Socrates; but that there was such a Man as Socrates himself. They should not dispute the Genij of Caesar, Cicero, Brutus, Marc Anthony; but avow, that there were never any such Men existing upon the Earth, and overthrow all credible History whatsoever. Mean while, all Men, but those who run such Lengths in their fantastical Incredulity, will from the Facts above-mentioned, rest satisfied, that there are such Things as Evil and Good Genij; and that Men have sometimes a Commerce with them by all their Senses, particularly those of Seeing and Hearing; and will not therefore be startled at the strange Fragments of Histories, which I am going to relate of our young Duncan Campbell . . . (101)

Bond suggests that if we cannot accept testimony or sensory perception as evidence, we can have no “history” or “Christian Religion” since history and religion are based on these foundations. At times, Bond seems almost to elide “testimony of experience” with experience itself. Writers of the apparition narratives considered testimony from respectable people to be as reliable as a scientific experiment or a report about the existence of another continent. Waller notes that Glanvill, for example, suggested that testimony about witches from a reliable source was no different from testimony provided by someone who had seen Robert Boyle’s air pump (28). Boyle himself supported Glanvill in his fight to prove witchcraft was real, writing to Glanvill in 1672 with a “detailed report of an alleged Irish witch whose powers he had personally verified.”x Waller also notes that Boyle “discoursed at length on the alleged phenomena of ‘second sight’ . . . .” Bond’s narrator, being of a similar mind to Glanvill, rejects and dismisses skeptical readers, saying that “free-thinkers” and “unbelieving Gentlemen” should just “lay down [his] Book” and not “read one Tittle further” (121).

Four years after Bond’s work, Haywood published A Spy Upon the Conjurer, and the narrator, Justicia, asserts the same biographical and apologetic purposes as Bond’s narrator does. However, Haywood effectively subverts the role of the authoritative and trustworthy gentleman “relator,” replacing him with an unreliable female narrator. Whereas Bond’s narrator presents himself as an authorized biographer who is writing to a wide audience, Haywood’s narrator Justicia, as Bullard points out, is an unauthorized “spy” whose epistolary argument is directed to an audience of one: her friend, an unnamed lord (174). Although Bond’s narrator consistently asserts authority and credibility, Haywood’s narrator regularly interjects details that will likely lead readers to question her authority and credibility. To some degree, this self-deprecating approach is common for Haywood, and scholars have argued about the authority of other Haywood narrators, such as her Female Spectator and Invisible Spy. xi However, in those texts, the narrators do, at times, assert and defend their own authority, and at times, their credibility is affirmed even by other voices. In contrast, Justicia’s only claim to authority is her intimacy with Campbell, and even that factor is subverted by her position as a “spy.” Ultimately, in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, neither Justicia nor anyone else vouches for her credibility; rather, they only question it.

Early in the text, Justicia herself suggests that one of her reasons for presenting her epistolary episodes to her reader is that she, as a woman, is not fit to judge:

As I communicate my Thoughts of this Affair only to one whose good Nature and Friendship I am secure of, I deal with that Confidence which I take to be the most distinguishable Testimony of Sincerity. However, as Custom, and the natural Austerity of your Sex denies to ours those Advantages of Education, which alone can make either capable of judging, I shall submit to the Opinion of those whose Learning renders their Sentiments more to be relied on, and should esteem it as a prodigious Obligation if your Lordship would, at some leisure Hour, favour me with a Line or two on this Head. (18)

Justicia argues that because she, like all women, is denied the “Advantages of Education,” and is, therefore, not truly “capable of judging,” she is sharing her testimony with the lord, so that he can offer a final judgment about Campbell. Justicia thus assigns herself a very different role from Bond’s narrator, who proudly claims, “I take upon myself a very great Task; I erect myself as it were into a kind of a Judge: I will sum up the Evidences of both sides; and I shall, wherever I see Occasion, intimate which Side of the Argument bears the most Weight with me” (260). Although he acknowledges that his readers will function as a “jury,” he, unlike Justicia, confidently accepts the role of judge, and he never offers evidence that would contradict his credibility. Although Justicia tells her reader she cannot fully function as judge, her name suggests she embodies judgment and justice, and this irony creates tension. As a result, Haywood’s readers—not her narrator—truly are invited to be the judges and jury of Justicia’s claims. Because of the questionable credibility of the narrator, and because of the second-person “you” to whom she speaks, the position of “reader as judge” is more authentic with Haywood than with Bond, giving Haywood’s text a more skeptical and literary turn.

At one point, Justicia does attempt to assure her skeptical reader, the unnamed lord, that he can trust her judgment. This assurance is complicated, however, by the fact that, in the past, he has accused her of bias, and by the earlier claims made by Justicia, herself, acknowledging that she does not always trust her own judgment. Nevertheless, Justicia says,

I hope your Lordship will not believe me guilty of the least Partiallity or Bigottry, (as you once told me) since I faithfully assure you, I neither have, nor will, in the Course of these Memoirs, avouch any thing without consulting my Judgment, and first answering within my self, all the Objections that can possibly be made against it. (41)

The last sentence of this passage suggests that Justicia is claiming a commitment to a kind methodical doubt that requires one to suspend final judgment until all doubts have been replaced by certainty. By making this statement, she demonstrates a keen awareness of the value of such doubt when trying to ascertain and report truth and when trying to be perceived as a trustworthy source. Her claim is seemingly undermined, however, when, just a few lines later, she challenges one of Campbell’s customers who expresses doubt about a prediction that Campbell has written down for her: “Why, Madam, said I, as soon as I had read [the prediction], should you question the Truth of what is here set down?” (42). With this challenge, Justicia suggests that the customer’s doubt about Campbell’s prediction is unreasonable. Justicia’s question seems like a strange one to ask of a woman who is approaching fortune-telling with what might be considered reasonable skepticism, especially after Justicia has just acknowledged the necessity for thoroughly doubting such claims and pursuing “all the objections” that could be made against those claims.

In fact, Justicia, too, once believed Campbell to be an impostor and “was ridiculing every Body who seem’d to speak favourably of him” (3). As a convert, however, she now expects others to believe that his gifts are real, based merely on the evidence of a prediction that is written on a piece of paper, and it is the people who doubt his words whom she finds to be “blinded,” suggesting it is they, rather than the deaf Campbell, who have flawed or limited perception. Justicia’s expectation for unquestioning belief suggests that she operates from a place of bias and that, as such, her analysis of evidence cannot fully be trusted. In the above passage, she admits that the unnamed lord has in the past accused her of “Partiallity or Bigottry,” a trait that still seems to be firmly in place.xii Justicia, then, is hypocritical. She claims to engage in sufficient doubt before assenting to a belief, yet the evidence of her narrative suggests that she does otherwise. Jenny Davidson has examined “hypocrisy’s usefulness as a central topos for defining and contesting narrative authority” (112). Although Davidson focuses primarily on moral hypocrisy rather than logical hypocrisy, Justicia’s fallacious double standard also functions as an indicator of her narrative authority, or lack thereof.

Justicia’s hypocrisy perpetuates as she consistently fails to practice a method of doubt. In fact, just a few pages after her claim that she will consider all “objections,” she contradicts herself—and also echoes Bond’s narrator—as she expresses scorn for those who are too skeptical:

I do not think any thing can be more provoking, than to hear People deny a known Truth, only because they cannot comprehend. Some fancy themselves very wise, in affecting to ridicule all Kinds of Fortune-telling, and tho’ they do happen (which I confess is a Wonder) to meet with one really skilful in the Art, yet because they cannot imagine by what Means he came to be so, are willing to run him down as the most ignorant of the Pretenders.—How should he know—and—how is it possible he can tell us? are Words commonly us’d, even by those who are convinc’d by Experience that he can. (44)

Like Bond’s narrator, Justicia privileges sensory experience and credulity over doubt, but unlike Bond’s narrator, she is an explicitly flawed relator. At one point, she is even chastised by Campbell himself for the poor judgment that runs in her family; he says they all are easily duped by flattery (130). His criticism of Justicia’s judgment and her lack of skepticism serve to compound the reader’s uncertainty about her credibility—and, therefore, about Campbell, too. If readers are to believe Justicia when she says that Campbell has great “penetration” of others, then readers should trust Campbell when he says that Justicia’s judgment is flawed. However, if readers trust Campbell that Justicia’s judgment is flawed, then maybe they should not trust her judgment about Campbell, which would imply that maybe Campbell should not be believed when he says that Justicia does not always reason well. In this circular consideration of credibility and credulity, the reliability of relators becomes like a snake swallowing its own tail (or “tale,” as the case may be), and although it is unclear who can be believed, themes about belief and judgment are unquestionably in play. It seems clear that, if the first-person narrator is unreliable, as she certainly seems to be, one must consider the possible satire at work in the text along with the likelihood that Haywood’s authorial purpose (and her attitude towards Campbell) should not be equated with Justicia’s narrative one.

Although Justicia does not have all of the qualities of the unreliable narrators found in later fiction, she does have the kind of questionable reliability one sees in other early eighteenth-century texts. Tracing the history of the unreliable narrator, Ansgar Nunning says that Maria Edgeworth’s Castle Rackrent (1800) is “one of the earliest instances in British fiction of a full-fledged unreliable narrator” (57). However, late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century writers, including Aphra Behn and Daniel Defoe, created narrators with dubious reliability who require evaluation by readers. For example, Karen Bloom Gevirtz points out that, in part three of Love-Letters from a Nobleman to His Sister, “Behn . . . [uses] the seemingly reliable narrator to explore how people deceive not only each other, but also themselves” (53). Although Behn’s narrative structure in Love-Letters (1684-1687) is much different from the consistent first-person point-of-view one finds in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, they share concerns about authority and self-deception.

Readers confront similar questions about narrative authority in Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1722), which, as Bannet argues, also invites judgment from the reader. Defoe’s reader

is invited to work with the agreement or disagreement between H.F.’s testimony and that of other witnesses, whom he also hears. [The reader] is required to use “diligence, attention, and exactness” in determining how far H.F.’s evaluation of the testimonies of witnesses is true to the reality of things and how far H.F. is himself a reliable witness; and he is asked to “proportion consent to the different probabilities.” (51)

Just as Defoe’s readers must evaluate H.F.’s testimony, Haywood’s readers must evaluate Justicia’s reasoning and determine if her testimony is “true to the reality of things.” With A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood creates a text that appears to be a biography like Bond’s, but by using the narrative strategies of fiction, she actually creates an account of Campbell that requires more active judgment from readers.

These rhetorical differences suggest that A Spy Upon the Conjurer is not merely a continuation of Bond’s credulous, Campbell-endorsing agenda but rather a skeptical challenge to the kind of credulity exhibited by his text. These differences also challenge assessments that deem Haywood’s central purpose to be unequivocal promotion of Campbell. King suggests, for example, that

A Spy Upon the Conjurer began as a piece of hack work, a kind of infomercial, if you will, intended to plug Duncan Campbell, a deaf-mute fortune-teller, quack doctor, and by the 1720s, member of Eliza Haywood’s literary set. . . . Haywood, in 1724 already a seasoned professional, set out, it would seem, to crank out a straightforward promotional piece—the plan apparently was to string together anecdotes testifying to the seerer’s [sic] wonderful gifts—but somewhere along the way she seems to have become interested in Campbell as a brother of the pen. (“Spying” 183)

Although I do not dispute that Haywood recognized the market value of her narrative or that she was interested in the written nature of Campbell’s fortunes, the fictionality and unreliability of her narrator suggests that she might have set out to write something more than a “straightforward promotional piece.” In addition, in King’s political biography of Haywood, which only gives a few sentences to A Spy Upon the Conjurer, she calls the text a “fascinating variant on the scandal chronicle” (Political 183). Although, to some extent, this is true—it does, like Haywood’s other scandal narratives, include references to various people in and out of her circle, especially Sansomxiii—the text is even more reflective of the conventions of biography and the apparition narrative, invoking those conventions in order to mock them, attacking credulity in order to privilege skepticism.

With this aesthetic, Haywood is not only satirizing credulous writers, but she is also engaging skeptical readers. Davis has suggested that readers (and writers) of the early eighteenth century had a difficult time making distinctions between fact and fiction (Factual 76-77). However, Kate Loveman argues otherwise, saying that readers recognized the differences and saw it as their job to avoid being duped and that the early eighteenth-century readers were both astute and eager to identify “shams” (2-3, 10-12). As Loveman explains, “There was a general agreement that a wary, enquiring disposition was a valuable asset in reading, and a necessary defence against error and deception” (34). Readers knew their roles as skeptics, but the proper rhetorical strategies or aesthetics needed to be in place in order for them to perform that role. In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood not only employs the rhetorical strategies to elicit readerly skepticism, but her subject, a deaf fortune-teller, serves as a case study for the fear of being “duped.” The newspapers during the early 1700s often included stories about duplicitous individuals arrested for fraudulent fortune-telling, and Justicia, herself, even offers accounts of such frauds.xiv For example, she tells the tale of a man who goes from one money-grubbing fortune-teller to another “till his Money was all gone,” and she also discusses fortune-tellers who “deceive the ignorant Wretches that confide in them” (25, 126). Haywood also has other texts that caution readers against fortune-tellers. In Present for a Servant Maid (1743), for example, she warns servants to avoid the “wicked Designs” of these “Pretenders to Divination,” and in The Invisible Spy (1755), the narrator gives an account of a woman taken in by a fortune-teller, and at length, he criticizes these “impostors” and the “credulous part of mankind” who visit them. By focusing on a fortune-teller in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood invites readers to put on an “enquiring disposition” and do their skeptical work.

Haywood’s focus on the stories of Campbell’s clients also expands the context of the conflict between skepticism and credulity. The male writers of apparition narratives and other anti-skeptical texts were concerned with threats to empiricism and religious belief. As a result, they typically focused on questions related to natural philosophy and God. Even their arguments about witches and apparitions were ultimately meant to support arguments about science and religious belief. As Jayne Elizabeth Lewis puts it,

Apparitions became the protagonists of a long line of hefty works that fixed matter-of-fact accounts of their manifestation within the frames of Protestant theology and natural philosophy, thereby working a perverse reconciliation between these two discourses on reality. (87)

In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood invokes the conventional touchstones of empiricism—experience and perception—but her questions and concerns tend to focus more on people than on theology or natural philosophy. This text, like others by Haywood, highlights the fact that it is extremely difficult to gain knowledge about other people (and ourselves) even though such knowledge is necessary and can have significant consequences for our daily lives. When Haywood shifts the epistemological conversation to the topics of Campbell’s clients, who are mostly women, she inserts questions about relationships and women’s concerns into the epistemological conversations of the early eighteenth century. As Gevirtz argues, the epistemologies of the natural philosophy, or New Science, practiced by the Royal Society, “valorized the isolated individual (the man)” and, therefore, “the individual who could not or ought not exist as an isolated entity (the woman) was removed from the systems of knowledge production” (29). And as Judy A. Hayden puts it, “As science moved out of the household and into the universities and various institutions, an important avenue of access for women in this new knowledge began to close” (5). In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood not only interrogates traditional methods of knowledge-making, but also, by focusing on household matters such as money as marriage, she challenges the closure around what counts as valuable knowledge.

The special significance of the epistemological power of fortune-telling also is addressed by Jennifer Locke in a study of Frances Burney’s Camilla, in which Locke notes that fortune-telling, in the eighteenth century, offered a potential way of knowing that “surpassed and went beyond scientific observation,” a way of knowing that was particularly valued by women (708). She says, “The majority of eighteenth-century texts advertised themselves as containing exotic, ancient, or occult knowledge that could provide information different from what was provided by conventional epistemologies.” In fact, one of the last letters in A Spy Upon the Conjurer is from someone asking Campbell about “Sir Isaac Newton’s System of Philosophy” and “how near it comes to Truth” (247). Campbell, who calls himself “a living practical System or Body of new Philosophy” (qtd. in Capoferro 138), claims to provide the occult or extra-scientific knowledge that is inaccessible to others without second sight— knowledge about the New Science itself, as well as knowledge about other people and their intentions that cannot be determined reliably through the five senses. As Locke points out, such knowledge would be of particular interest to women:

The strong connection between women and fortune-telling in the period can in part be explained by the relative unpredictability of women’s economic and social lives. Women’s futures were understood as difficult or even impossible to forecast and, therefore, were the most in need of an alternative form of projection. (705)

Campbell’s clients, who are mostly women, have questions about whom they will marry, whom they should marry, who is lying to them, and so on. They see deception all around them, and they recognize that their perceptions and experiences are often insufficient for discovering truth. They seek Campbell’s preternatural answers to these questions because appearances (and people) often are deceiving, and individual judgments often are biased. Through this context, Haywood makes clear the stakes of credulity, especially for women. By using the language of the New Science, she mocks naïve empiricism even as she assigns gravity to the problems of domestic deception.

Questions about other people prove to be as challenging to answer as questions about nature and God. In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, knowledge about people is thwarted not only by flawed perception and biased judgment, but also by the fact that other people are often willfully deceptive—a problem that pervades Haywood’s Campbell narrative as well as most of her other texts. Furthermore, for Haywood, deception can be almost impossible to penetrate, and often the person being deceived can only learn the truth when either the deceiver chooses to reveal him- or herself, or when the deceived person engages in deception of his or her own in order to gain or regain epistemic privilege. Readers find such to be the case in Fantomina (1725), in which, in order to penetrate the deceptions of Beauplaisir, Fantomina (or Lady — ) must, herself, become a deceiver. Deceptions expand to an even larger scale in Memoirs of a Certain Island Adjacent to the Kingdom of Utopia (1725) and The Adventures of Eovaai (1736), both of which feature not only extended tales of individual deception, but also central plots based on mass delusion that is nearly impossible to detect or overcome. The central plots of Anti-Pamela (1741) and The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (1753) also turn on deception and the difficulty of discovering truth. Deception is even the first point of concern in A Present for the Servant Maid (1743), a “conduct manual” that warns about deception in the marketplace (as well fraudulent fortune-tellers). In fact, Haywood has few texts that do not involve people deceiving each other for their own personal gain.

A Spy Upon the Conjurer has a particularly noteworthy example of the difficulties of gaining knowledge about other people, and Justicia uses this example as a key piece of evidence in her argument for Campbell’s legitimacy. To that end, she spends significant time explaining an episode in which a fifteen-year-old young lady visits Campbell to find out “when she shou’d get a Husband” (88). Justicia gives a lengthy, entertaining account that includes the young woman’s first meeting with Campbell, along with accounts of subsequent information-gathering (“spying”), by which Justicia learns about the events as they unfold. Justicia has pursued information about the young woman because of both curiosity and her intent to defend Campbell, and in doing so, she learns that all has come to pass exactly as Campbell predicted it would. Specifically, the young woman got married but now is suing for a separation because her husband treats her poorly and because he behaved strangely in bed on their wedding night. In response to the suit, the husband agrees to divorce his young wife under one condition: that she never again associates with her previous suitor, Mr. E—d M—n. The husband then summons Mr. M—n to explain the binding agreement and to ridicule him, upon which action Mr. M—n becomes enraged and challenges the husband to a duel. At this moment, the husband reveals that he cannot fight in a duel because he is, in reality, a woman:

The Person challeng’d presently discovered herself to be a Woman, and consequently unfit for such an Encounter as the other demanded. — Having pluck’d off her Perriwig, all the Company knew her to be a Lady who had long been courted by Mr. E—d M—n; but the other’s Fortune being greater, had alienated his Affections to her: On which she had dress’d herself in Mens Clothes, and contriv’d this Strategem to disappoint his hopes. (93-94)

In short, a jilted woman has retaliated against the man who rejected her by posing as a man and stealing his preferred beloved. Justicia explains that no one begrudged the Lady for her cross-dressing trick and that all praised her for her “ingenuity.” Even the deceived young woman was grateful to this trickster rival who prevented her marriage to Mr. M—n, who was clearly a man of inconstant and selfish affections.

It is striking that, in this episode, the deceived woman finds the deception quite understandable and forgivable. However, even more striking is the magnitude of the deception and the degree to which the lady’s direct sensory impressions fail to sufficiently inform her of the real sex of her spouse and how that reality differs from appearances. Granted, one might imagine ways in which, during this time period, such a deception before marriage might be achieved, and the young woman does find her husband’s bedroom behavior to be “very different from what might be expected” (91). One should also grant that such cross-dressing disguises are a common plot device in Haywood’s texts and in other eighteenth-century fiction and, therefore, might be considered to be an ordinary and insignificant comedic turn in the plot.xv Nevertheless, in the context of the foregrounded questions that pervade this text—questions of belief, doubt, and the reliability of evidence—this incident suggests that our senses can be fooled even about what appears to be the simplest questions of reality, such as the sex of one’s lover. As Justicia herself acknowledges elsewhere in the text, “Things are frequently very different in Reality from what they appear to the World or sometimes even to their greatest Intimates” (44-45).

Although Bond’s narrator bases much of his defense of Campbell on sensory experience and testimony, anecdotes like the above demonstrate that Haywood’s text, despite Justicia’s credulity, recommends little trust in either. In Haywood’s narrative, Campbell is the only one who can truly distinguish between appearance and reality. The five senses of his customers are not sufficient for determining truth, a reality which challenges empiricism and implies that only by extra-sensory perception can truth be determined. However, since the legitimacy of Campbell’s extra-sensory perception remains in doubt, readers are left with no reliable method to gain knowledge or determine truth—even though Haywood puts them in the position to do so. In other words, Haywood’s skeptical aesthetic puts the readers in an authoritative position at the same time that she leads them to question their ability to exercise that authority. If Justicia has failed as an authority on Campbell (and she has), she also has demonstrated the difficulty of reaching a conclusion about the central question-at-issue, namely Campbell’s legitimacy, and while the question about Campbell, himself, might not seem particularly urgent, it is only the most explicit question in the text. Many other questions are equally difficult to answer, namely the questions asked by Campbell’s clients. The question about Campbell’s legitimacy, then, signifies, to some degree, all of the epistemological problems in the text.

Nussbaum writes that, “unquestionably, Campbell’s station as a hot commercial property motivated Haywood’s opportunistic desire to capitalize on the popular rage that made his conjectures marketable” (Limits 51). I agree that Haywood likely was capitalizing on the market potential of Campbell’s story—Lewis reports that apparition narratives were “cash cows for a prenovelistic publishing industry” (85)— but it is important not to overlook or negate the epistemological concerns of Haywood’s text, along with the degree to which it enters a pre-existing conversation begun by Bond and other anti-skeptical writers, thereby engaging with dominant concerns of Enlightenment intellectual culture. In A Spy Upon the Conjurer, Haywood demonstrates that truth is elusive at the same time that she charges her characters and her readers with epistemic responsibility and authority. This double bind of skepticism and responsibility leaves the text’s characters—and, necessarily, its readers—in crisis, and it demonstrates a central challenge of the modern individual: the problem of determining what is true.

With this argument about the genre and purpose of A Spy Upon the Conjurer, I do not mean to undermine other scholars’ claims about how the text addresses issues such as marginalization, deafness, and curiosity. In fact, by recognizing A Spy Upon the Conjurer as a woman writer’s fictional and skeptical challenge to anti-skeptical works typically penned by men, other readings of the text can become even more layered. When Justicia says to one of Campbell’s clients, who is holding a piece of paper with Campbell’s prediction on it, “Why, Madam, said I, as soon as I had read it, should you question the Truth of what is here set down?”, she is echoing the credulity that one finds in Bond’s text and in other apparition narratives. Haywood, however, gives the reader many potential answers to such a question, attacking credulity and privileging skepticism in its place and inviting readers to ask questions of her own text—and what she has “here set down”—ultimately placing interpretive authority in their hands.

Cuesta College

NOTES

i Campbell’s fortune telling is mentioned in 1709 by Richard Steele in The Tatler (No. 14) and in 1714 by Joseph Addison in The Spectator (No. 560). These texts, combined with Haywood’s Campbell text, suggest he practiced as early as 1709 and as late as the early 1720s.

ii See Nussbaum, Limits; Nussbaum, “Speechless”; King, “Spying”; and Farr, Queer Deformities.

iii Regarding Defoe, for example, Maximillian Novak has said, “Defoe knew a great a great deal about the supernatural and the occult. How much he actually gave credence to and how much he thought to be complete hokum is difficult to say” (11).

iv Thorne’s use of “anti-romance” here suggests that he does not mean “romance” in terms of literary genre, but rather he means “love” or “courtship.”

v See Wilputte, “Textual Architecture” and “Haywood’s Tabloid Journalism.”

vi For Defoe’s de-attribution and arguments for Bond as author, see Baine 137-80 and Furbank and Owen. Spedding accepts Baine’s attribution to Bond in his Bibliography (642). Other contemporary texts about Campbell include The Friendly Demon, which Spedding says is thought to be by Defoe (655). Spedding argues against attributing the Secret Memoirs to Defoe or to Haywood (as others have done) and argues that attribution to Campbell, himself, is more plausible (654-56). For the attribution of Bond’s book to Haywood, see Richetti’s introduction to The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (xxxvii).

vii See King, “Spying,” 183. For more details on the relationship and timeline of Bond, Sansom, and Haywood’s connections to Campbell, see Spedding 142-143.

viii Also see The Dumb Projector (1725), which focuses in large part on an extended “jest” (or test) of Campbell’s claims to second sight. Despite being different in tone from A Spy Upon the Conjurer, The Dumb Projector is still attributed to Haywood by Spedding 229-230.

ix For more on “free-thinkers,” see Hutton 208-25.

x In the late seventeenth century, belief in the actual presence of witches was becoming outdated, but even educated people generally acknowledged the reality of witchcraft because of biblical foundations for “pacts with the Devil.” However, most were skeptical about individual accounts of witches or apparitions (Waller 16-17; Amussen 154-155). By 1736, belief in witchcraft was considered “to be a vulgar notion bred of ignorance and credulity” (Davies 7).

xi For discussions about authority in The Female Spectator, see Shevelow 171; Powell 156, and King, Political, 111. For a discussion of authority in The Invisible Spy, see Froid.

xii “Partiallity” is a central concern in numerous Haywood texts, including The Female Spectator (1744-46) and The Adventures of Eovaai (1736), so its inclusion here is not incidental; rather, it marks the beginnings of a theme that carries throughout Haywood’s body of work.

xiii For a detailed discussion of Haywood’s attention to Martha Fowke Sansom in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, see Spedding 141-143.

xiv See, for example, The Flying Post; or, The Post Master, 28 February 1716, for an account of an imposter deaf and dumb fortune-teller who was “put in the House of Corrections at Nantwich, and can both speak and hear.” See also The Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 27 June 1724: “One Susana Howard of Windmill-Hill, a pretended Fortune-Teller was last Monday Night committed to Bridewell, by Colonel Mitchel, for defrauding a young married Woman of 10 s.”

xv For example, in A Spy Upon the Conjurer, there is one other cross-dressing deception, and Haywood’s Invisible Spy (1755) features an extended and comedic cross-dressing trick in which a young woman dresses as a man to save her friend from an undesirable marriage. For a more tragic episode of cross-dressing, see Haywood’s The Double Marriage: or, the Fatal Release (1726).

WORKS CITED

Amussen, Susan D. and David E. Underdown. Gender, Culture and Politics in England, 1560-1640: Turning the World Upside Down. Bloomsbury, 2017.

Baine, Rodney M. Daniel Defoe and the Supernatural. U of Georgia P, 1969.

Bannet, Eve Tavor. See Tavor, Eve.

Bullard, Rebecca. The Politics of Disclosure, 1674-1725. Pickering and Chatto, 2009.

Campbell, Duncan. Secret Memoirs of the Late Mr. Duncan Campbel [sic], The Famous Deaf and Dumb Gentleman. Printed for J. Millan, at the Green Door, the Corner of Buckingham-Court; and J. Chrichley at the London-Gazette, Charing-Cross, 1732. https://archive.org/details/gu_secretmemoirs00camp. Accessed 21 Apr. 2018.

Capoferro, Ricardo. Empirical Wonder: Historicizing the Fantastic, 1660-1760. Peter Lang, 2010.

Cavendish, Margaret. Observations on Experimental Philosophy. Edited by Eileen O’Neill, Cambridge UP, 2001.

Conrad, R. and Barbara C. Weiskrantz. “Deafness in the 17th Century: Into Empiricism.” Sign Language Studies, vol. 45, 1984, pp. 291-379. Project Muse, doi: 10.1353/sls.1984.0010.

Davies, Owen. Witchcraft, Magic, and Culture. Manchester UP, 1999.

Davis, Lennard J. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body. Verso, 1995.

—. Factual Fictions: The Origins of the English Novel. Pennsylvania UP, 1997.

Donoghue, William. Enlightenment Fiction in England, France, and America. Florida UP, 2002.

Farr, Jason S. Queer Deformities: Disability and Sexuality in Eighteenth-Century Women’s Fiction—Haywood, Scott, Burney. 2013. UC San Diego. eScholarship, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7sq8k58m. Accessed 21 Apr. 2018.

The Friendly Demon, or the Generous Apparition; Being a True Narrative of a Miraculous Cure, Newly Perform’d upon that Famous Deaf and Dumb Gentleman, Dr. Duncan Campbel, By a Familiar Spirit that Appeared to Him in a White Surplice, like a Cathedral Singing Boy. London: Printed and Sold by J. Roberts in Warwick-Lane, 1725. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, http://find.galegroup.com/ecco/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ECCO&userGroupName=msgbs&tabID=T001&docId=CW3312044529&type=multipage&contentSet=ECCOArticles&version=1.0&docLevel=FASCIMILE.

Froid, Daniel. “The Virgin and the Spy: Authority, Legacy, and the Reading Public in Eliza Haywood’s The Invisible Spy.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 30, no. 4, 2018, pp. 473-493. https://doi.org/10.3138/ecf.30.4.473. Accessed 24 July 2018.

Furbank, P. N. and W. R. Owen. Defoe De-Attributions: A Critique of J. R. Moore’s Checklist. Hambledon, 1994

Gevirtz, Karen Bloom. Women, the Novel and Natural Philosophy, 1660-1727. Palgrave, 2014.

Hayden, Judy A. Introduction. The New Science and Women’s Literary Discourse, edited by Hayden, Palgrave, 2011, pp. 1-15.

Haywood, Eliza. The Dumb Projector: Being a Surprising Account of a Trip to Holland Made by Mr. Duncan Campbell. With The Manner of his Reception and Behaviour there. As also the various and diverting Occurances that happened on his Departure. London: Printed for W. Ellis at the Queen’s Head in Grace-church-Street; J. Roberts in Warwick-lane; Mrs. Bilingsly at the Royal-Exchange; A. Dod without Temple-bar; and J. Fox in Westminster-Hall, 1725. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, http://find.galegroup.com/ecco/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ECCO&userGroupName=msgbs&tabID=T001&docId=CW3314324855&type=multipage&contentSet=ECCOArticles&version=1.0&docLevel=FASCIMILE.

—. The Female Spectator, in Selected Works of Eliza Haywood, set II, vol. 2. Edited by Kathryn R. King and Alexander Pettit, Pickering and Chatto, 2001.

—. The Invisible Spy. Edited by Carol Stewart, Routledge, 2016, Kindle edition. First published 2014 by Pickering and Chatto.

—. Present for a Servant Maid, in Selected Works of Eliza Haywood, set I, vol, 1. Edited by Alexander Pettit, Pickering and Chatto, 2000, pp. 224-225.

—. A Spy Upon the Conjurer: A Collection of Surprising Stories, with Names, Places, and particular Circumstances relating to Mr. Duncan Campbell, commonly known by the Name of the Deaf and Dumb Man; and the astonishing Penetration and Event of his Predictions. London: Sold by Mr. Campbell at the Green-Hatch in Buckingham-Court, Whitehall; and at Burton’s Coffee-House, Charing-Cross, 1724. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, http://find.galegroup.com/ecco/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ECCO&userGroupName=msgbs&tabID=T001&docId=CW3312695993&type=multipage&contentSet=ECCOArticles&version=1.0&docLevel=FASCIMILE.

Hooke, Robert. Preface. Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon. London: Printed by Jo Martyn and Ja. Allestry, Printers to the Royal Society and are to be sold at their Shop at the Bell in S. Paul’s Church-yard, 1665. Unpaginated. Early English Books Online, http://gateway.proquest.com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2003&res_id=xri:eebo&rft_id=xri:eebo:citation:879330429.

Hutton, Sarah. British Philosophy in the Seventeenth Century. Oxford UP, 2015.

Kareem, Sarah Tindall. Eighteenth-Century Fiction and the Reinvention of Wonder. Oxford UP, 2014.

King, Kathryn R. A Political Biography of Eliza Haywood. Pickering and Chatto, 2012.

—. “Spying Upon the Conjurer: Haywood, Curiosity, and ‘The Novel’ in the 1720s.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 30, no. 2, 1998, pp. 178-193.

Lewis, Jayne Elizabeth. “Spectral Currencies in the Air of Reality: A Journal of the Plague Year and the History of Apparitions.” Representations, vol. 87, no. 1, 2004, pp. 82-101. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/rep.2004.87.1.82.

Locke, Jennifer. “Dangerous Fortune-telling in Frances Burney’s Camilla.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 25, no. 4, 2013, pp. 701-720. Project Muse, doi: 10.3138/ecf.25.4.701. Accessed 24 Sept. 2013.

Loveman, Kate. Reading Fictions: Deception in English Literary and Political Culture, 1660-1740. Routledge, 2008.

McKeon, Michael. Origins of the English Novel, 1600-1740. Fifteenth Anniversary Edition, Johns Hopkins UP, 2002.

“News.” Flying Post; or, the Post Master, 28 Feb. 1716 – 1 Mar. 1716. 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection. http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6t35Q6.

Noggle, James. The Skeptical Sublime: Aesthetic Ideology in Pope and the Tory Satirists. Oxford UP, 2001.

Novak, Maximillian. “Defoe’s Spirits, Apparitions, and the Occult.” Digital Defoe: Studies in Defoe and His Contemporaries 2.1, 2010, pp. 9-20. https://english.illinoisstate.edu/digitaldefoe/archive/spring10/features/novak.pdf. Accessed 13 Mar. 2018.

Nunning, Ansgar. “Reconceptualizing the Theory, History, and Generic Scope of Unreliable Narration: Towards a Synthesis of Cognitive and Rhetorical Approaches.” Narrative Unreliability in the Twentieth-Century First-Person Novel, Edited by Elke D’hoker and Gunther Martens, Walter de Gruyter, 2008, pp. 29-75.

Nussbaum, Felicity A. The Limits of the Human: Fictions of Anomaly, Race, and Gender in the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge UP, 2003.

—. “Speechless: Haywood’s Deaf and Dumb Projector.” The Passionate Fictions of Eliza Haywood, Edited by Kirsten T. Saxton and Rebecca P. Bocchicchio, Kentucky UP, 2000, pp. 194-216.

Parker, Fred. Scepticism and Literature: An Essay on Pope, Hume, Sterne, and Johnson. Oxford UP, 2003.

Powell, Manushag. Performing Authorship in Eighteenth-Century English Periodicals. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP, 2012.

Richetti, John. Introduction. The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy. UP of Kentucky, 2005.

Shapin, Steven. A Social History of Truth: Civility and Science in Seventeenth-Century England. Chicago UP, 1994.

Shevelow, Kathryn. Women and Print Culture: The Construction of Femininity in the Early Periodical. Routledge, 1989.

Spedding, Patrick. A Bibliography of Eliza Haywood. Routledge, 2004.

Tavor, Eve. Scepticism, Society, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. St. Martin’s, 1987.

Thorne, Christian. The Dialectic of Counter-Enlightenment. Harvard UP, 2009.

Waller, John. Leaps in the Dark: The Making of Scientific Reputations. Oxford UP, 2004.

Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer. 27 June 1724, pp. 2903. 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6t8X72.

Wilputte, Earla A. “Haywood’s Tabloid Journalism: Dalinda, or the Double Marriage and the Cresswell Bigamy Case.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 14.4, 2014, pp. 122-142. Project Muse, doi: 10.1353/jem.2014.0044.

—. “The Textual Architecture of Eliza Haywood’s Adventures of Eovaai.” Essays in Literature 22.1, 1995, pp. 31-44.

—. “‘Too ticklish to meddle with’: The Silencing of The Female Spectator’s Political Correspondents.” Fair Philosopher: Eliza Haywood and the Female Spectator, Edited by Lynne Marie Wright and Donald J. Newman, Bucknell UP, 2006, pp. 122-140.