Atlantic Slavery and Ludic Freedom

The game is not, though, equally willing to allow for ambiguity with respect to what lead writer Darby McDevitt calls the “delicate subject” of slavery. McDevitt explains: “slavery is a theme, but I didn’t want it to be sensational…The books I read were full of horror stories, and I tried to work in some of those, at least anecdotes and stories, and make it a background fact of life” (Campbell). ACIV accordingly treats slavery as too delicate a subject to risk the contingency of ludic experience.[1] Though in some respects the game allows what Bogost calls “free-form transitions” between play styles — defined in part as the ability to “orient one’s conception of right and wrong in relation to a whole host of activities” — where slavery is concerned, ACIV resorts to “crude prohibition” (154-56). The game, in other words, limits ludic freedom at the expense of historical authenticity. ACIV’s twenty-first century narrative overwrites eighteenth-century realities regardless of the ways in which the resultant foreclosures contradict the parameters of play in other aspects of its simulation; the fiction of the Animus thus reveals itself as such wherever and whenever the narrative overrides the possibility or the probability of “free” interactions between players and the facts of the early eighteenth-century Atlantic slave trade.

Slavery was the sine qua non of Golden Age piracy in its final decade. The end of the War of the Spanish Succession left thousands of sailors adrift, and Johnson specifically identifies “the Returns of the Assiento, and private Slave-Trade, to the Spanish West-Indies” as a major reason why “these seas are chose by Pyrates” (26). “To many white pirates,” W. Jeffrey Bolster writes, “the majority of blacks were pawns, workers, objects of lust, or a source of ready cash,” and though able black sailors “like … Kidd’s quartermaster were welcome in the Brethren of the Coast, it was with the understanding that black and white pirates preyed on black and white victims” (15-16).[2] In 1718, at a time when up to a third of the vessels journeying to Western Africa were harassed by pirates — slavers making the best pirate ships — black sailors constituted the majority of Blackbeard’s crew (Linebaugh and Rediker 165).[3] A General History specifically mentions slaves, slavery, or the slave trade 31 times, and the word “negro” or one of its variants 50 times — four more times than “death” — or approximately once every 14 and nine pages, respectively.

In short, chattel slavery does not readily recede into the background of life in the West Indies during this period. It was indeed often the immediate business of piracy — a “fact of life” necessarily among those foremost in the minds of pirate crews whenever they intercepted prizes laden with human cargo. Though, as Rediker observes, “formerly enslaved Africans or African Americans who turned pirate posed questions of race” just as “women who turned pirate called attention to the conventions of gender,” the game largely skirts the questions raised by the intersections of slavery and piracy and instead imposes upon its simulation moral codes and fiscal positions inconsistent with the realities of the time (Villains 14).[4] There is no authentic history of Golden Age piracy the game could present that would not put the player in a position to engage in slave trafficking, and though ACIV makes the Trinidadian slave-turned-pirate Adéwalé quartermaster of the Jackdaw, Kenway’s ship, and later sees him too inducted into the order of the Assassins, the game never compels the pair, the player, or indeed any pirates from Johnson’s history to confront even the possibility of such engagement.

A contradiction therefore emerges in the space between the players and the pirates whose lives they experience through Kenway’s memories. Though the main plot points must unfold in a particular order, the open-world format permits a degree of choice with respect to side missions.[5] Players can choose to accept or reject various assassination contracts and ship-based missions, and in the “Kenway’s Fleet” metagame they can determine which if any naval engagements they wish to undertake in order to build their fortunes by securing trade routes and transporting commodities. The morality of those choices, though, is entirely pre-scripted and prescribed. This, for example, is contract 25 (fig. 9):

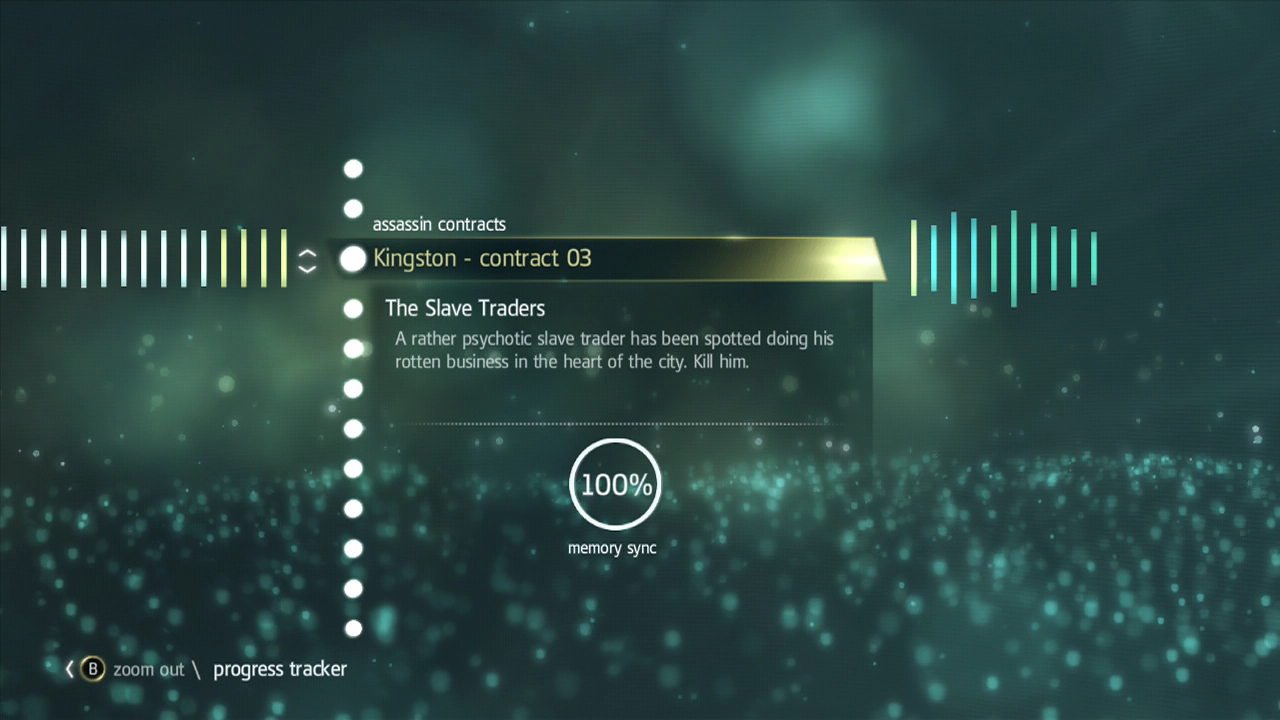

Contract 03 is somewhat more straightforward (fig.10):

The game includes 30 optional assassination contracts, which if successfully undertaken add to the player’s account a cash reward of between 30,000 and 45,000 reales. Targets include smugglers, grave robbers, corrupt judges, tyrannical officers, maniacal captains, and an assortment of would-be evildoers affiliated with the Templars, but fully five of the 30 send Kenway in pursuit of slavers whose manners and business the contracts describe as “rotten,” “brutal,” “villainy,” “particularly cruel,” and “unusually sadistic.”

All five missions roundly condemn the slave trade — a position mandated by the tenets of the Assassin Order. None, though, identify any of the targeted slavers as pirates. The missions thus follow the narrative in securing the slave trade behind a cordon sanitaire that for the most part protects players from this part of the pirate’s life. Little or nothing is said about slavery even within a circle of friends that includes Blackbeard, whose Queen Anne’s Revenge was the French slave ship La Concorde before he captured it, and Bartholomew Roberts, who served as second mate aboard a slaver and turned pirate when Howell Davis took the ship in 1719.[6] Once made captain in his own right (following Davis’s murder by Portuguese slavers), Roberts “so despised the brutal ways of slave-trading captains” that he ordered or himself gave a “fearful lashing to any captured captain whose sailors complained of his usage” (Rediker, The Slave Ship 22-23). Kenway apparently need never be exposed to similar experiences in order to arrive at similar conclusions; nor does the player ever get to hear of them. Though players can refuse to accept any or all of the contracts, they cannot change their impetus, and any slaves freed in the wake of a slaveholder’s assassination either automatically fill empty slots in the Jackdaw’s crew or vanish into the background.

Even deeper in the “background,” in a metagame accessed through but not actually part of the primary historical simulation, the game simply erases slavery and slaves from its picture of Atlantic commerce. As commodore of a fleet of captured ships, Kenway can (under the player’s direction) dispatch crews and cargoes to dozens of ports, including those of the Triangle Trade. Each dot indicates a port at which the player can exchange goods for ship upgrades, artifacts, treasure maps, and cash. Trade routes extend as far north as Galway, London, and Bristol and as far south as South Africa. The above map (fig. 11) highlights Cape Verde and three West African ports associated with it: Dakar, Bissau, and Ziguinchor. All four were established sites of the slave trade before, during, and after the period in which the game is set; so too were Benguela and Luanda, represented by the coastal dots to the southeast.[7] The icons at the top of the map, though, show that the holds of Kenway’s fleet contain only rice, tobacco, cocoa, wine, and olive oil. The map thus shows the sites of slavery, but not what put those sites on the map in the first place.

With respect to slavery and race, then, the game abandons the strategic ambiguity it established and ultimately maintained regarding the questions of gender and sexuality raised by Bonny and Read. Rather than risk players’ creating “incorrigible social meaning” by attempting to profit from slavery, as some undoubtedly would, ACIV — no doubt following the North Star of profitability to Ubisoft — fixes Kenway’s moral compass.[8] The designers’ decision to downplay or remove the slave trade from the game and to resolve Kenway’s involvement with slavery as an absolute and a priori rejection rather than a flexible series of financial calculations more in keeping with the nature of historical piracy clearly reveals the primacy of narrative control over even those operations the outcomes and potential significations of which remain separate from the main story. The game could but does allow for eighteenth-century actions that should be but are probably not beyond players’ willingness to undertake — even if such restrictions critically undermine the integrity of a fictional framework premised upon the possibility of experiencing a realistic past.

NOTES

[1] As Andrew Elliot and Matthew Kapell explain, “ludic” “carries with it the implication of spontaneous or aimless play” and emphasizes “the sense that games are not designed as artifacts only to be looked at or understood narratively like films or television” (3). More broadly, the ludic facilitates or encourages exploration and meaning-making rather than the strictly linear progression through assigned tasks; see W.W. Gaver, et al., “The drift table: designing for ludic engagement.”

[2] Woodard recounts the story of the Whydah Gally, a 300-ton three-master with room “for 500-700 slaves or a large cache of plundered treasure.” The ship “had everything a pirate might want” and was taken in 1717 by the pirate Samuel Bellamy (156-58). A “Whydah Gally style bell” appears in the game as a collectible but comes with no note of the ship’s purpose.

[3] For pirates’ preference for slave ships, see Arne Bialuschewski, “Black People under the Black Flag: Piracy and the Slave Trade on the West Coast of Africa, 1718–1723.”

[4] The omission received notice in major outlets. Chris Suellentrop, for example, writes that ACIV “virtually ignores the vital role that chattel slavery played in the economy of” the “Caribbean” (“Slavery as New Focus for a Game”).

[5] Mary DeMarle refers to this design as a “gated story”; see “Nonlinear Game Narrative,” in Game Writing: Narrative Skill for Videogames.

[6] Blackbeard neither kept nor sold the “miserable human cargo” aboard La Concorde, but he did leave them on Bequia (part of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), “where they would soon be rounded up by the French captain and his men” (Konstam 191).

[7] The Portuguese in Cape Verde had relied upon slave labor since the sixteenth century; the cotton plantations there ensured that the islands remained important to the slave trade throughout the 1700s (Barry 40-42). For the histories of Benguela and Luanda in the period, see Roquinaldo Ferreira, “Slaving and Resistance to Slaving in West Central Africa.”

[8] The phrase belongs to Stephanie Partridge, who argues that, “some video games contain details that anyone who has a proper understanding of and is properly sensitive to features of a shared moral reality will see as having an incorrigible social meaning that targets groups of individuals… [V]ideo game designers have a duty to understand and work against the meanings of such imagery” (304).