Collecting and Collectibles

There was more to life in the early eighteenth-century than piracy. The game provides in-game access to a supplementary database that grows as the narrative unfolds but leaves players to determine the extent of their interaction with its contents. By inviting players to become avid collectors, for example, the game not only remediates the cultural phenomena of early modern antiquarianism and the curiosity cabinet but also creates the potential for the social meaning of those phenomena to be brought to bear upon the game itself. If the Animus brings the player into the eighteenth century, then the database once again brings the eighteenth century back out into the modern world of Abstergo and Ubisoft to address and reform the cultural status of the video game as a form of entertainment.

Video games have long required players to acquire objects scattered or hidden throughout their worlds. A distinction, however, must be made between “collecting” in ACIV and the simpler “gathering” of weapons, medicines, and other practical items. In addition to descriptions of these materials, the database stores information on characters historical and fictional, locations and landmarks, animals, ships, and sea shanties. It also houses “Documents” and an “Art Collection,” both of which require more deliberate effort to complete. Beyond the messages in bottles and electronic notes referring to the series’ overarching fictions, the Documents database includes pages from twenty actual texts: players can, for instance, view images of and from Athanasius Kircher and Christoph Scheiner’s Mundus Subterraneus (1664-65), Diego Muñoz Camargo’s History of Tlaxcala (1585), the fifteenth-century Voynich manuscript, and the pre-Columbian Dresden Codex (Codex Dresdenis). The Art Collection holds an additional fifty items ranging from paintings by Claude Lorrain and Peter Lely to fine furniture and musical instruments to zoological specimens and antiquarian objects such as Taino figurines, Aztec sculptures, and Nigerian jewelry. To collect the rare manuscripts, players must unlock the locations of “secret” treasure chests, journey to each one of those locations, dispatch their guards, and open the chests; items in the Art Collection come from opening trade routes in the Fleet metagame or purchasing them outright.

To create a world in which Kenway can participate in an ersatz culture of collecting makes historical sense. The collecting career of Hans Sloane, another kind of “self-made man,” as Marjorie Swann describes him, began in Jamaica, and by the 1690s the practices that culminated in his extensive collection had significant social importance beyond the upper echelons in which eventually he found himself:

Lower down the social scale, men in seventeenth-century England assembled ‘cabinets of curiosities’ rather than collections of art…Antique coins, scientific instrument, minerals, medals, rare or unusual zoological specimens, plants, natural and manmade objects from Asia and the Americas, intricate carvings, portraits of important historical figures — the early modern English cabinet of curiosities was an exuberant hodgepodge of ‘the singular and the anomalous.’ (195; 1-2)[1]

The ACIV database combines such curiosities — “collectibles,” in video game parlance — with the art and texts of collections proper. The poor, Welsh privateer and pirate Kenway would therefore seem to seek not only the wealth and power that comes from piracy but also the social status of his betters.[2] In the case of the manuscript pages, Kenway comes into their actual possessions; according to the database, they all once belonged to the immensely wealthy planter and lieutenant governor of Jamaica, Colonel Peter Beckford.[3]

Collecting, then, might be said to function as another act of social subversion akin to the cross-dressing of Bonny and Read, the establishment of a pirate republic in Nassau, or any number of other simultaneously political, economic, social, and piratical activities. By game’s end, Kenway’s “hideout” on Grand Inagua, if fully upgraded, includes a façade, towers, gardens, and a guesthouse; the Art Collection bedecks his walls and fills his shelves (fig. 12). The hideout thus becomes what Swann describes as an “elite house,” the purpose of which by the1670s was “no longer to demonstrate lineage” but rather “to dazzle in its profuse display of rarities, all of which bespoke the owner’s financial ability to amass objects of no use-value” (148). The objects are indeed useless, as several players have noted: in a message thread asking, “what’s the point of buying art,” for example, one such player observes that the collection “seems like a waste of money” and wonders if it serves an “in-game purpose” (Lear). Anonymous NPCs chat in corners as if taking in the spectacle of bat-nosed figurines and Mayan yoke-form vessels amid the more conventional markers of material wealth. Kenway seems, at least beyond Britain, to enjoy the trappings and social status of a gentleman, even though he has literally built his grand estate atop a massive pile of pirate booty secreted in the underground caverns.

A similar logic of social or cultural elevation applies to ACIV itself. In a franchise premised upon the possibility of accessing the past, collecting and the collection may indeed constitute the game’s most immediately self-relevant examples of remediated cultural phenomena. If “a collection is always steeped in ideology and functions as a site of processes of self-fashioning that may serve either to reinforce or to undermine the dominant categories of the society in which the collection appears,” then the presence in a video game of a collection that would not be out of place in an eighteenth-century curiosity cabinet again focuses attention on the self-reflexivity of ACIV as a video game (Swann 8). “In general terms,” Angus Vine writes, “the antiquary conceived of himself as bridging the gap between past and present, affording ‘olden time’ presence so that it might speak to or inform the current time. For this reason John Aubrey likened antiquarianism to ‘the Art of a Conjuror who makes those walke and appeare that have layen in their graves many hundreds of yeares: and represents as it were to the eie, the places, customs and Fashions, that were of old Time’” (3, 5).[4] ACIV strives to do the same; in the Animus, the dead walk again, and if they do not follow precisely the same paths charted by the historiographers, they nevertheless offer a vision of the fragmented past imaginatively reconstructed and made whole.[5]

Though already subject to critical scorn by the late seventeenth century, antiquaries’ devotion to and curiosity about the past survived into and beyond the period of the game’s historical setting. Their belief that “artefacts excavated from barrows, ancient buildings and even the landscape — as well as manuscripts — could be made to yield up the secrets of the past” echoes in the artworks, artifacts, and manuscripts re-presented in the game. The old media though which seventeenth- and eighteenth-century antiquaries sought to “reconstruct the ‘shipwreck of time’” become the contents of a new medium that pursues or, as ACIV particularly demonstrates, could be made to pursue the same or similar ends (Sweet xvi).[6] The inclusion of European art and objects from the period simply suggests that it has become another part of history in need of recovery and reconstruction. Within the fictional framework of the series, that process proceeds not by collecting material fragments of cultures, but rather by collecting material fragments of people in the form of DNA, through which the Animus allows Templar and Assassin agents to access genetically encoded memories. The game offers itself and its simulation as real-life answers to that fantasy: not the advanced technology of a lost civilization, but perhaps (for now) the next best thing — a stop between the antiquarianism of an earlier age and that of an imaginable future.

At best, ACIV can only uncomfortably occupy a position in the antiquary or indeed any other scholarly tradition. Its acknowledged inaccuracies and ludicrous framing narrative make it a work of historical fiction, and though that fiction relies upon serious historiography, the game in general neither asks nor expects to be taken seriously as such itself. ACIV knows its limits and understands its obligations as a game built, like Kenway’s house, upon piracy and gold. It also, however, gestures toward the potential of the medium to do other kinds of work, and it implicates the player as a potential obstacle or asset to achieving what might be its more culturally elevating ends. On the one hand, players can ignore the Art Collection and Manuscripts sections completely; the game requires no interaction with them. Alternatively, they can cultivate an intellectual curiosity by viewing the collections directly through the database or via a room that, as one player grudgingly puts it, “you never go into, unless you wander around the house. Blah” (“Where does the art show up?”). Though once accessed, the programmatic interface and structures of the database set the operational parameters of the experience, players must first actively choose to become “subversive” gamers in their willingness to do more than hack and slash their way through the Golden Age of Piracy in pursuit of pure entertainment.

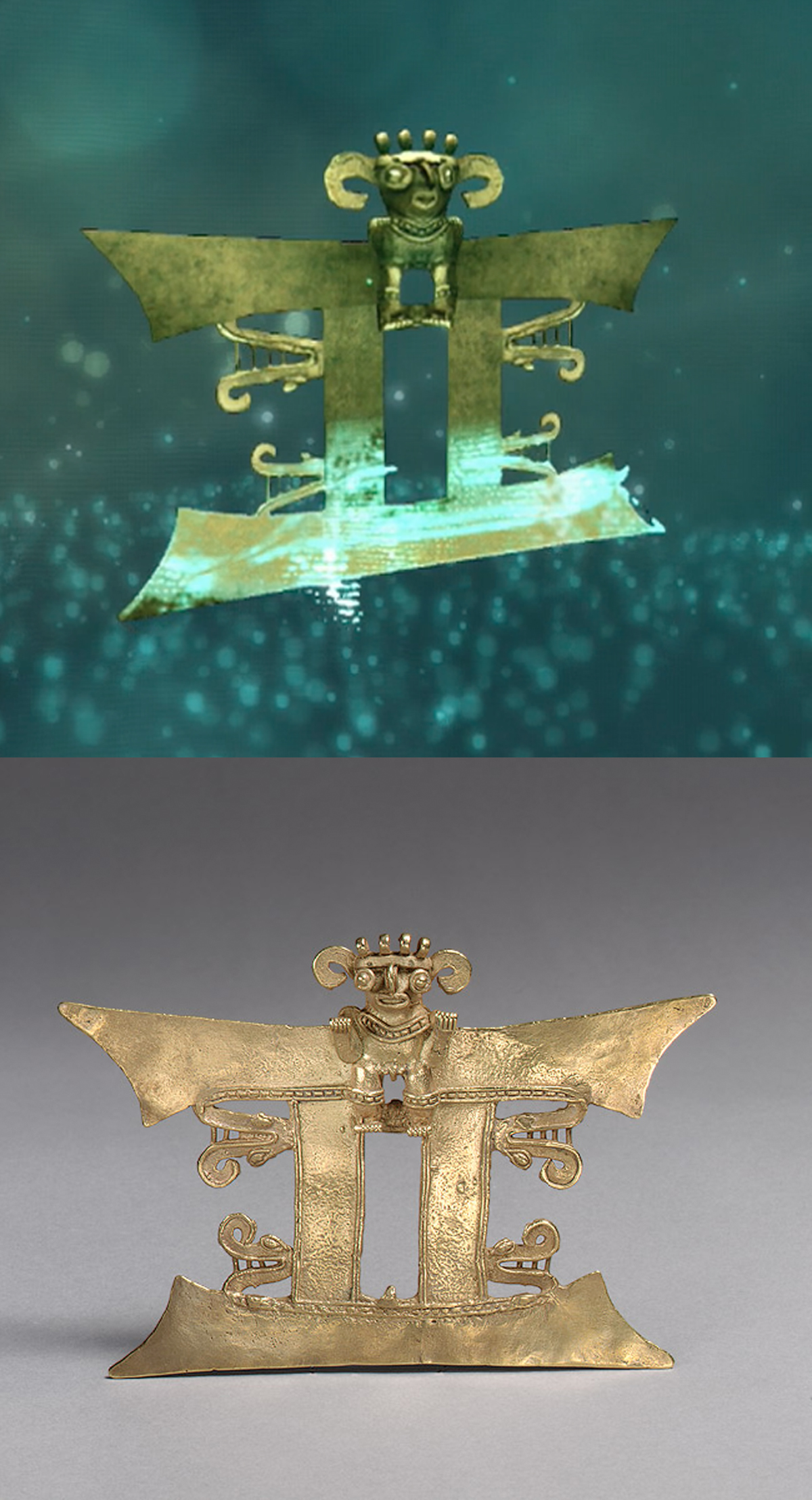

Fig. 13: Top: “Bat-Nosed Figurine,” in the Art Collection, Assassin’s Creed IV. Ubisoft (2013). Bottom: “Bat-Nosed Figure Pendant,” (66.196.17), in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (2000).

Without this kind of self-fashioning, neither Kenway in the eighteenth century nor ACIV in the twenty-first can entirely escape or alter the dominant categories into which their societies have placed them. Those who choose to interact with the collection will experience the added functionality of the game as a virtual museum: the Art Collection represents the holdings of some seven institutions, but 39 of its 50 come from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[7] The images are clearly adapted from the Met’s online catalogue, and they come with abbreviated versions of the Met’s descriptions (fig. 13). To read them is to learn, for instance, that the natives of Veracruz may have used mirrored costume elements to connote high rank, that one could construct an expensive commode out of layered brass and tortoise shells, and that Hendrik Richters made some of the finest oboes of the early eighteenth century. ACIV combines the collecting of the amateur antiquary with the authority of a curated museum exhibition and thus (potentially) elevates the cultural status of the game. The objects and information add an educational element likely outside the general horizons of expectation for a pirate-themed, action-adventure virtual experience — particularly one like that advertised in Abstergo’s cliché-laden Devils of the Caribbean trailer.

NOTES

[1] Swann quotes Lorraine J. Daston, 461.

[2] “Initially pursued as an elite cultural form, the collection was soon adopted — and adapted —by ambitious, middling sort men” (Swann 194). Though less than middling, Kenway is certainly ambitious.

[3] The database supplies Beckford’s first and last names but not his rank or titles. The manuscript pages were “stolen sometime after 1705”; Beckford’s death in 1710 makes him rather than his son, also Peter, their most likely original owner.

[4] Vine quotes John Aubrey (4).

[5] “This act of the imagination,” writes Peter N. Miller, “lies at the heart of the antiquary’s reconstructive ambition” (31).

[6] This theorization of content and medium belongs to Marshall McLuhan; see Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (8).

[7] The institutions are not identified within the database, but the objects and their homes are easily located online. The other six are: the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; the Royal Gallery, Windsor; the Whydah Pirate Shipwreck Museum, Provincetown; the Science Museum, London; Dulwich Picture Gallery, London; and Staatsgalerie Schleissheim, Munich. Two items, the beaver pelt and Scherer’s Globe, could not be positively placed.