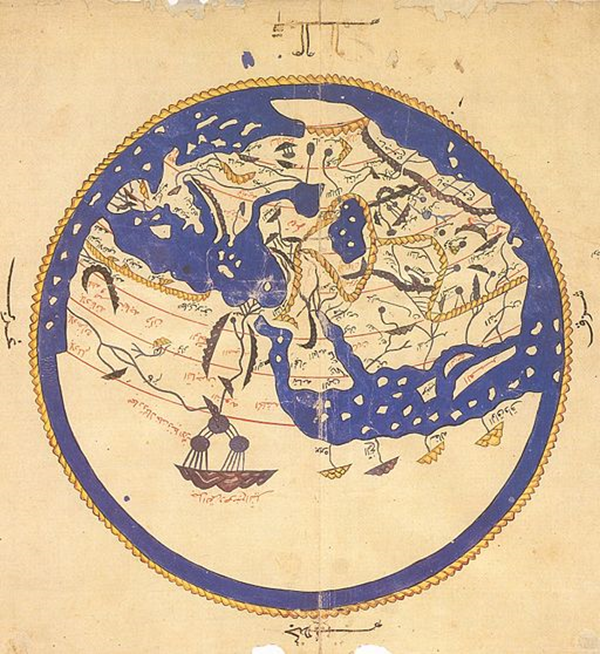

IN 1154, MUHAMMAD al-Idrisi drew one of the most detailed medieval world maps, the Tabula Rogeriana, for King Roger II of Sicily (Fig. 1). The map reflects the ancient geographical theory that Africa’s eastern and western rivers share a source. This image of Africa had a longstanding effect on how Europeans conceptualized the continent’s interior, one that lasted well into the eighteenth century. As late as the 1730s and 40s, travelers were still searching for conclusive evidence on whether the Niger, the Gambia, and the Senegal were three different rivers or one and whether they converged with the Nile in the hinterland. In Francis Moore’s Travels into the Inland Parts of Africa (1738), for instance, he points out that both Herodotus and al-Idrisi suggest that “a Branch of the Nile runs westward, and after a very long Course falls into the Atlantick Ocean…by the Gambia, Senegal, and Sierra Leone, being augmented in its Passage by all the Waters which fall to the South of Mount Atlas” (28). Moore proposes, as further evidence for this, the fact that hippopotamuses and crocodiles inhabit both the Nile and the Gambia and that the two rivers exhibit similar flooding patterns (28-29).i

Not simply an abstract geographical quandary, the question of whether Africa’s western and eastern waterways connected shaped Europe’s economic and imperial engagement with the continent. In his introduction to John Newbery’s World Displayed (1759), Samuel Johnson writes that the Portuguese were told by an ambassador from Benin that a Christian country lay to the east (Abyssinia) and that “by passing up the river Senegal [the Christian king’s] dominions would be found” (xxvi). It is only after attempts to find this overland route failed that the Portuguese began sailing to Ethiopia around the Cape of Good Hope (xxviii). Similarly, British explorers like George Thompson (1618) and Richard Jobson (1620) sailed up the Gambia in the hopes that, rather than crossing the Sahara as Arabic traders did, they would be able to tap into “the golden trade, by the South-parts” (Jobson 4-5). These fantasies of access went hand-in-glove with descriptions of Africa as a land packed with untold wealth found in geographies such as Leo Africanus’s History and Description of Africa (trans. 1600), which described Sahel cities rich and cosmopolitan, or Olfert Dapper’s Description of Africa (trans. 1670), which included an image of West Africans casually scooping gold out of a stream.ii The discovery of a hydraulic network that spanned the continent would enable access to Africa’s interior ivory fields and gold mines, the location of which African potentates kept secret well into the nineteenth century, and it would allow Europeans to sidestep indigenous brokers.iii Goods might also then be transported between Europe and the East Indies without needing to be shipped around the Cape or through Ottoman waters.iv

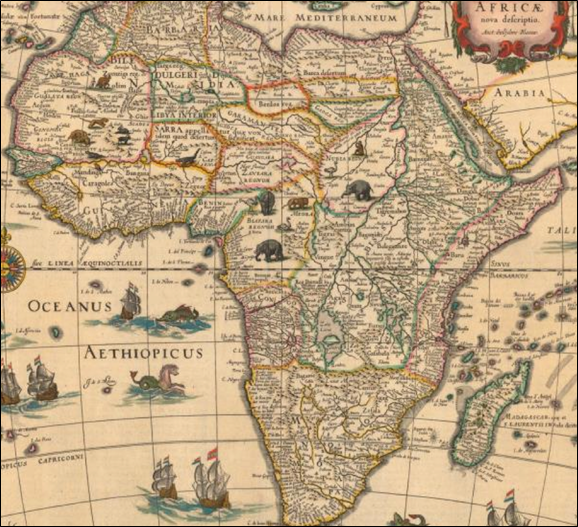

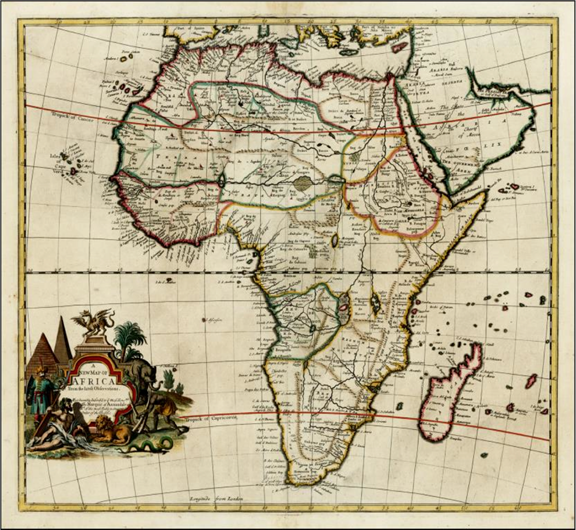

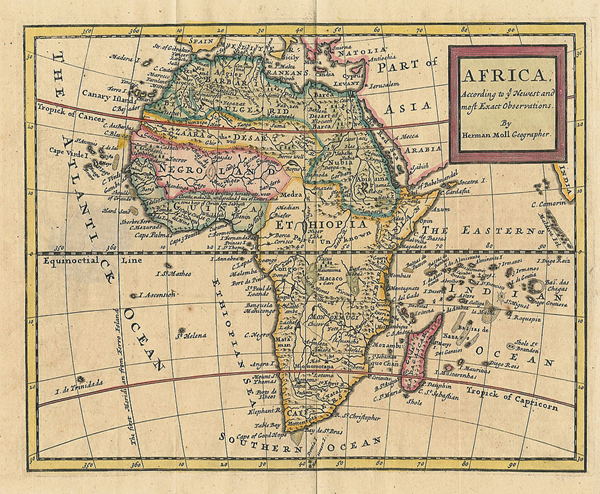

Early maps of Africa echoed these fantasies. “Geographers, in Afric maps” may have “o’er unhabitable downs/ Place[d] elephants for want of towns” (180-82), as Jonathan Swift once quipped, but far more frequently, they placed major waterways where there are none. Maps by Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1635), John Senex (1721), and Herman Moll (c. 1715) all show the major western rivers and the Nile within centimeters of one another, flirting if not outright connecting, and all three add the Congo River into the mix, indicating that it, too, might be a tributary of the Nile that extends all the way through the southwest quadrant of the continent (Figs. 2-4). v Their cartouches and the decorative details make promises about what one would find if one followed these rivers. Senex’s cartouche shows an African figure bent over and gathering armloads of elephant tusks scattered on the ground. Elephants and rivers are inextricably coupled in the center of Blaeu’s map and occupy more of the interior than do human settlements. The geographical story that such maps tell far exceeded the empirical data available to Europeans at the time.

Daniel Defoe’s Captain Singleton (1720) enters this discourse about Africa’s rivers in ways that test the limits of early Enlightenment mapping practices. David Livingstone argues that a map’s “cultural power” (154) comes from the way it is distanced from the place it represents: such “uncoupling of text and context gives the impression that the map discloses universal truth” (158). Captain Singleton closes this distance again. Text and context are rejoined as the eponymous protagonist and a troop of Portuguese mutineers use a contemporary map of Africa to navigate from Madagascar to the European forts on the Gold Coast. The resulting narrative increasingly mirrors the story that seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century maps told about Africa.vi Following a serendipitously placed network of rivers through the center, Singleton and the crew reach the west coast so wealthy from the gold and ivory littering the interior that critics have read the text as unrepentant propaganda for the Royal African Company.vii However, as Singleton moves further away from the well-documented coasts into the largely unknown center, his geographical descriptions also become increasingly incredulous, haunted by contradictory details and zoologically impossible beasts that provoke sensory stupefaction. As the text aligns early Enlightenment mapping conventions with Singleton’s suspect accounting practices, the image of “universal truth” showcased by maps, both inside and outside the text, is splintered.

Defoe’s interest in geography has been well noted, though it is often assumed that he was mimicking and appropriating, and not necessarily commenting on, the methods of his day.viii Pat Rogers writes, for example, that “there is something mechanical about the mode of narration” in Captain Singleton, that “it is rather too easy to see Defoe poring over his maps and geography books at home” (113). This image is warranted by Defoe’s own recommendations in The Behavior of Servants in England Inquired Into (1726) and A New Family Instructor (1732) that any time one reads a history or a travelogue, they ought to do so with the appropriate maps open in front of them (47, 13). But Defoe was not an uncritical consumer of geography. He bookends his History and Principal Discoveries and Improvements with the caution that “What’s yet discover’d only serves to show/ How little’s known, to what there’s yet to know” (iv, 240), and he suggests that true knowledge of the world only comes through slow and “imperfect . . . gradations” as confirmed fact is built upon confirmed fact (305). He was aware that very real barriers prohibited Europeans from gaining ground in Africa, either literally or epistemologically. As he writes in the Atlas Maritimus and Commercalis (1728):

tho the Nile, the Niger, and the Congo are all great Rivers, yet they are navigable so little a way, or their Navigation is so interrupted by Cataracts and Water-falls, or by long overflowing of the Waters, or by the violent Currents, that there is no Correspondence by them. (263)

Access to the continent’s gold is equally stymied: the Europeans “have not a Mark of Gold in the whole Trade, but what we must get of the Negroes by fair trading . . . it is brought down from the Inland Countries by the Negroes, nor can we tell particularly from what Part of the Inland Countries it comes” (270). Though Defoe was enthusiastic about colonial projects in Africa and believed that, if Europe fully invested in the continent, it would “out-do in Profit to us the Commerce of both the Indies” (History 302), he also cautioned against undertaking “dangerous and impracticable Projects, such as mad Men cannot, and wise Men will not meddle with” and believing in “dark Schemes and unintelligible Proposals, which have neither probability of success to encourage the attempt, or rational foundation” (vii).ix Captain Singleton, I argue, tempers its own colonial fantasies as it questions the rational foundation of European ideas about Africa’s rivers and cautions the reader not to be taken in by geographical representations that elide empirical data with speculative infilling.

Implausible though Singleton’s trek across the interior may appear, Defoe positions it within very real eighteenth-century discussions about African geography and navigation. Their journey summons in reverse the routes that men like George Thomson, Richard Jobson, and Bartholomew Stibbs hoped to discover by traveling east on West Africa’s rivers. Like the explorers of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century travel narratives, Singleton and the sailors are tasked with figuring out the most efficient way to traverse Africa, with little knowledge of what lies ahead other than bits of empirical data, hearsay, personal experience, and information from indigenous guides. However, unlike their historical counterparts, who turned around when they reached the places where the Gambia or the Senegal Rivers were no longer navigable, Singleton and his crew push on. The entire continent sits between them and Europe, and the only way out is through. As the marooned sailors debate the best course to take, they consider, and then discard, the more conventional ways that Europeans got around Africa. They can’t build a boat large enough to take them east to Goa or to sail south around the Cape. Like Robinson Crusoe, Singleton has already spent time in Barbary captivity, and he fears that sailing north will result in being “killed by the wild Arabs, or taken and made Slaves of by the Turks” (38). This conversation sketches Africa’s eastern coastline and lays out the size and scope of the task before the men. It also reminds the reader how little about Africa’s interior had actually been documented and that the detailed travel accounts that Europeans did have only describe a tiny portion of the overall landmass. As Singleton puts it, “we were upon a Voyage and no Voyage, we were bound by some where and no where: for tho’ we knew what we intended to do, we did really not know what we were doing” (emphasis original).x By describing their trajectory as both “a Voyage” and “no Voyage,” Singleton squeezes his account into the space between experiential travel and imaginative speculation, on the threshold of the known and the unknown. The starting place and the goal—the coasts—are clear, but the path that joins them is not.

The men try to decide how to accomplish the first step of this non-voyage—crossing the Mozambique Channel—and their debate reiterates the piecemeal nature of European knowledge about Africa. The sailors first turn to the locals of Madagascar. As Singleton points out, their “Correspondence with the Natives was absolutely necessary,” not only to ensure provisions and a place to stay while they gather their resources, but also for information about how to proceed (45). When they ask their African hosts about the journey, their response is that “there was a great Land of Lions beyond the sea” (46). So, the men share the lore that they have each heard about the distance between the island and the mainland. “Some said it was 150 Leagues, others not above 100. One of our men that had a Map of the World shewed us by his Scale, that it was not above 80 Leagues. Some said there were Islands all the way to touch at; some say that there were no islands at all” (46). No one type of information is more authoritative than another in this jumbled discussion. The map, though ostensibly a text that “discloses universal truth,” is not trusted above local testimony or hearsay. It, too, is squeezed into the space between experiential travel and imaginative speculation.

In fact, Captain Singleton cautions the reader throughout the first half of the narrative that seemingly objective and empirical statements are not to be taken at face value. The most obvious example of this is the extent to which Singleton himself blends the rhetoric of scientific observation with the duplicity of his piratical character.xi As most travelers to Africa did in the early eighteenth century, Singleton adopts the role of scientific observer throughout the text.xii The Gunner, a man who Singleton describes as “An excellent Mathematician, a good Scholar, and a compleat Sailor,” teaches Singleton everything he knows about “the Sciences useful for Navigation, and particularly in the Geographical Part of Knowledge” (73). From this education, Singleton knows what to include in his account about geographical features, weather patterns, currents, plants and animals, etc. Jason Pearl compellingly observes that, as Singleton adopts the trappings of empiricism, his narrative plays out “a dynamic exercise, moving back and forth between experimental and abstract forms of knowledge” (109). Indeed, Singleton translates specific observations about the local landscapes into the retrospective language of the global throughout the text, inviting the reader to consider the relationship between the two and how one is transformed into the other.

However, Singleton notes multiple times that he “kept no journal” of his travels (4, 6, 52), casting suspicion on his use of scientific discourse and on his representation of Africa, even as he builds a narrative treasure-trove of gold, ivory, and slaves, ready for the taking. If the lack of reliable records is not reason enough to distrust the consistency of his methods, he tells the reader early and outright that “[thinking him] honest [would be] a very great mistake” (7). Hans Turley points out that critical readings of the novel tend to divide Singleton’s piratical adventures in the second half from his overland journey in the first, which “can be seen as a precursor to such novels as Heart of Darkness and other colonial and post-colonial works” (200). Yet, Singleton’s piratical character is part and parcel of Defoe’s commentary on the geographical strategies frequently used to represent Africa. By being honest about his dishonesty, performing his own version of the classic liar’s paradox, Singleton not only renders the boundary between truth and falsehood unstable; he throws his narrative into epistemological flux.xiii His account is neither a text that simply lies, nor one that divulges truth, but one that unapologetically collapses divides among science, speculation, and even intentional misdirection. His story is of a voyage and of no voyage, as he says, and it is impossible to tell where the accounting ends and the tales begin.

This instability has consequences not only for Singleton’s own representation of the continent, but also for those that the text invokes and evokes: the maps in Captain Singleton are put on the stand as well. Africa’s waterways, and the narratives that surrounded them dating back to classical texts, are both the physical and metaphorical guideposts of this examination. If they can agree on nothing else, Singleton says, “we all knew, if we could cross this Continent of Land, we might reach some of the great rivers that run into the Atlantick Ocean” (65), a notion that would have been reflected in whatever map they are carrying with them, as even a cursory glance of some of the most common ones shows (Figs. 2-4). Unsurprisingly, it turns out that the Gunner, that “excellent mathematician,” is the possessor of the maps, and Singleton refers to him as “our guide” throughout. But true to the scene in which the map is lumped in with other kinds of speculative discourse, it does not turn out to be a particularly steadfast tool, though it is a successfully coercive one, convincing Singleton and the sailors of its dependability even as it turns out to be wrong time and time again.

At one point, for instance, the Gunner is convinced that he’s found the Nile, or at least the lake that the Nile comes out of:

In three days march we came to a River, which we saw from the Hills, and which we called the Golden River, and we found it run Northward, which was the first Stream we had met with that did so; it run with a very rapid current, and our Gunner pulling out his Map, assured me that this was either the River Nile, or run into the great Lake; out of which the River Nile was said to take its Beginnings: and he brought out his Charts and Maps, which by his Instruction, I began to understand very well: and he told me, he would convince me of it, and indeed he seemed to make it so plain to me, that I was of the same Opinion. (120-21)

Singleton, who thinks by this point that he “undertand[s maps] very well,” has been seduced by the “plainness” of the maps and the Gunner’s explanation of them. Yet, a few pages later, they encounter another river, one that’s so big that they mistake it for the sea, and as Bob tells us, “My friend the Gunner, upon examining, said, that he believed he was mistaken before, and that this was the River Nile, but was still of the Mind, that we were before, that we should not think of a Voyage into Egypt that Way” (136). Shortly thereafter, the men have a discussion over what direction to turn next, which plots out the west coastline, just as their initial debate over how to get off of Madagascar plotted out the east. They are once again “bound by some where and no where.” Though Singleton wants the crew to go straight north in hopes of finding the Rio Grand (the Niger), the Gunner advises the crew to continue northwest in search of a tributary that runs into the Niger, the Gambia, or the Senegal Rivers. This “good Advice” was “too rational not to be taken” (147). After all, Singleton reminds us once more that the Gunner is “indeed our best Guide, tho’” it turns out “he happen’d to be mistaken [yet again] at this time.” These moments caution that seemingly objective and “plain” geographical representations, and in particular ones that suggest that the interior of Africa is filled with connected waterways large enough to be navigable by boat, can mislead and deceive.

By making the “Golden River” and the Nile one and the same, the text exposes the layers of this hydraulic fantasy. The Golden River is, of course, one of the nicknames for the Nile itself, which connotes its historical richness as the lifeblood of an ancient and wealthy civilization. The men are also literally pulling gold nuggets from the river with ease: “we seldom took up a Handful of Sand,” Singleton reports, “but we washed some little round Lumps as big as a Pin’s Head, or sometimes as big as a Grapestone, into our hands” (123). They find ivory as well, a “prodigious Quantity of Teeth” (117), “a hundred Ton of elephant’s teeth” (151). “They were no Booty to us,” Singleton laments, though the men “once thought to have built a large Canoe on purpose to have her loaded with Ivory.” They decide against it because they don’t yet know whether the path of rivers they are following will take them all the way through the continent. But once they find a village on the western side where they stay a few months with an English factor gone rogue, the English factor and several of the crew make two trips back into the interior and return with heaps of elephant tusks. Though it is unclear at times whether they will get the ivory all the way to the Dutch factory they are aiming for, Singleton tells us they ultimately do, via “the River, the Name of which I forgot, where we made rafts” (178). The fact that Singleton “forget[s]” the name of the river leaves open the possibility that any one of West Africa’s major rivers or their tributaries could lead directly into the abundant interior and join up with the source of the Nile, the Golden River. Such a connection promises both an immediate profit through the direct acquisition of gold and ivory and the long-term potential for sustainable trade. Indeed, it may not even be necessary to name which one of the western rivers leads to this wealth because perhaps they are, as some have argued, all one and the same.

Ivory and rivers replace human settlements in Singleton’s account as they do in Blaeu’s and Senex’s maps. However, Captain Singleton deconstructs this fantasy even as it repeats it. Singleton says early on in the narrative, “even the worst part of [Africa] we found inhabited” (62), and he and the crew are told by the indigenes of Madagascar “that there were a great many Rivers, many Lions, Tygers, and Elephants” on the mainland, but that there were also “People to be found of one Sort or another everywhere” (64). Whether Captain Singleton’s subsequent depiction of Africa as void of human settlement is a conscious bit of Singleton’s deception or just an inconsistency on Defoe’s part, it exemplifies the ways that contradictory or competing details about the continent often co-existed within the same representational space.xiv This is the case even on maps that appear not to indulge in artistic speculation. Instead of filling the interior of his map with decorative detail like Blaeu, for instance, Herman Moll labels it “Parts Unknown,” but rivers run through these words, breaking them into pieces. The absence of knowledge denoted by the words is juxtaposed against the speculative presence of the rivers, which blend seamlessly with the inlets and outlets around the coast, whose positions have been scientifically verified. This juxtaposition throws into sharp relief the fact that longstanding fictions about where Africa’s access points might lead remained fundamental to how Europeans imagined Africa, even as mapmakers simultaneously acknowledged they had no empirical evidence to back up such hypotheses. After all, as Heraclitus pronounced, rivers are shifting signifiers: in eighteenth-century Africa, they were both conduits and barriers; they simultaneously facilitated and foiled penetration into the interior.

The farther Singleton and the crew move away from the coasts, the more vexed his own geographical discourse becomes. His representational strategies default to another longstanding story Europeans told about Africa’s waterways: that monstrous beasts stalk their banks. Unlike the illusion of unfettered access conjured by European depictions of African rivers, descriptions of the animals that lurk around their edges are emblematic of the limitations of European penetration into African spaces, the anxious shadows of colonial ambition. Real animals, like the crocodiles and hippopotamuses Moore cites as evidence that the Nile and the Gambia are connected, posed a danger to anyone, African or European, who traveled by river. Travelogues almost always include an obligatory brush with death via crocodile, including Singleton’s own: the Gunner has to kill one by “thrust[ing] the Muzzle of his Piece into her Mouth” because “no bullet would enter her through the hide” (116). When the Gunner thinks he has found the head of the Nile, they decide not to backtrack and follow it to Egypt in part because of “the innumerable Crocodiles in the River, which [they] should never be able to escape” (121). Such dangers were as much a part of how African rivers were imagined as their potential riches. Blaeu’s map may promise an interior full of elephant ivory, but if that ivory is going to be carried out along the major western waterways, crocodiles bar the way. And as the inhabitants of Madagascar warn Singleton, he’s unlikely to encounter the “great many rivers” of Africa without encountering its “Lions” and “Tygers” too.

While animals like crocodiles and hippopotamuses limit physical travel in texts about Africa, imagined creatures signify the limitations of epistemological access to the continent. As Pliny described in Book 8 of his Naturall Historie, African animals were thought to congregate around watering holes and breed across species:

so many strange shaped beasts, of a mixt and mungrell kind are there bred, whiles the males either perforce, or for pleasure, leape and cover the females of all sorts. From hence it is also, that the Greeks have this common proverb, That Africke evermore bringeth forth some new and strange thing or other. (200) xv

These hybrids break the rules of taxonomy and speciation that naturalists were developing in the early eighteenth century to quantify unknown places and their inhabitants, suggesting that Africa’s interior defies scientific categorization.xvi

Defoe harkens back to Pliny’s proverb in other works to signify how Africa befuddles the senses of the European observer. In Robinson Crusoe, when Crusoe and Xury are “anchored in the mouth of a little river,” in sub-Saharan Africa, “as soon as it is quite dark” they see “vast great creatures ([they] knew not what to call them) of many sorts, come down to the sea-shore and run into the water” (21-22). The creatures terrify Xury and Crusoe. Crusoe can’t name them or locate the place where they come from. He can’t separate them from the darkness of night. Because Crusoe “could not see” the creatures, could only hear their “horrible noises” and “hideous cries,” he concludes that “there was no going for us in the night upon that coast” (23). He exhibits the existential anxiety Roger Caillois describes when humans encounter creatures that can blend into their surroundings: a literal “fear of darkness” manifests as disorientation, even “depersonalization” (100). Rather than taming the land and its occupants through his eyes and his pen, the observer is stymied.

Similarly, as Singleton and the men are refreshing themselves on the shores of yet another “Great Lake of water,” they find themselves among “a prodigious Number of ravenous Inhabitants, the like whereof, tis most certain the Eye of Man never saw” (113). Singleton speculates, “I firmly believe, that never Man, nor a Body of Men, passed this Desart since the Flood, so I believe there is not the like Collection of fierce, ravenous, and devouring Creatures in the world; I mean not in any particular Place.” At night, Singleton and the crew are consistently surrounded by “a prodigious Number of Lions, and other furious Creatures, [they] know not what about them, for [they] could not see them” (118). Their wailing is an assault on the ears, “Noise, and Yelling, and Howling” coming from “all sides.” They are “terrible Beasts” that Singleton and his crew “could not call by their names” (131). As Singleton slips into this discourse of animal hybridity, it flags his deviation from systematized eyewitness reporting into chaotic frenzy, where things that ought not be coupled crossbreed, resulting in offspring that are confusing and strange at best and monstrous at worst, a perversion of scientific order. Africa’s interior is a “particular place” (unique) because the interior is not documented or documentable through its particulars. Its defining factors in the British imagination are speculative details and long told stories.xvii

These eerie beasts are a critical counterpoint to the ivory and gold throughout the interior. Africa’s “open spaces are the space of the subhuman or the animal” in Captain Singleton, as Christopher Loar observes (134). The beasts’ “strange sound[s] . . . threate[n] death and madness” (136). But their uncanniness also belies the reliability of Singleton’s geographical representation. Because he can’t see, distinguish, or name any of the creatures, he is denied Adam’s dominion over the space, and he can no longer maintain the persona of the scientific observer who can objectively contain the world in a “grid of language,” as Foucault argues early naturalists did (113). As a result, the interior of Africa remains unmapped, for all intents and purposes, by the end of Singleton’s journey. It holds an embarrassment of riches, but it is also an illogical and inaccessible space, regardless of how seamlessly Singleton’s narrative connects it to the continent’s well-known and navigable coasts.

The result of Defoe’s recoupling of African maps and Africa in Captain Singleton results itself in a suspicious hybrid—a text that highlights the great distance between geographical representations and the places they purported to represent. Captain Singleton does not reproduce generic norms in a way that invites the reader to trust Singleton’s account as a probable reflection of Africa’s material reality. Rather, Captain Singleton “draws attention to” not just the “fabrication of all doctored accounts,” as Srinivas Aravamudan argues (81), but to the discursive and imaginative nature of all European representations of Africa’s interior in the early eighteenth century. Invoking maps within the text and evoking maps outside the text do not bring empirical or imperial security to Captain Singleton. Rather, the novel exposes the map as largely the product of speculative infilling rather than the product of measurements and observations from traditionally trustworthy sources. Maps, Captain Singleton reminds readers, are not universal truths over which European subjects have epistemological authority; rather, the hybridization between limited empirical data and global representation results in an unstable text. As Singleton’s own account mimics the narrative told by these early maps of Africa, it may create an alluring ideation of colonization and trade, but it also suggests that such appealing representations—like the piratical Singleton; like rivers themselves—embody a paradoxical duplicity.

Boston College

Figure 1. 1456 copy of Al-Idrisi’s world map. Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK. Wikimedia Commons. The lower left-hand landmass shows a river that stretches from the Nile Delta to the West African coast. The map is rotated 180 degrees from the original.

Figure 2. Willem Janszoon Blaeu, Africa (1635). Northwestern University Library, Evanston, IL. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. John Senex, A New Map of Africa from the Latest Observations (1721). Maps of Africa: An Online Exhibit. Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, CA.

Figure 4. Herman Moll, Africa, According to the Newest and most Exact Observations (c. 1715). Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5. Relief Map of Africa (2013). Wikimedia Commons.

NOTES

i Moore lays out the debate without weighing in, saying instead that he will leave it up to the reader to “compar[e] one Account with the other, and see whether there is a Probability that the Niger and the Nile flow from the same Fountains, or that the Niger and the Gambia are the same” (xi). He does, however, advocate for the reliability of al-Idrisi more generally, whom he refers to as the “Nubian Geographer,” on the grounds that he is “African” himself and thus, along with Leo Africanus, has “given a better Account of the inland of Africa as any other” (viii).

ii Leo Africanus’s History was translated in to English by John Pory in 1600. Olfert Dapper’s Description was translated by John Ogilby in 1670. Both were foundational source texts for many accounts of Africa in the eighteenth century.

iii Willem Bosman bemoans this fact in a letter to a friend published in his New Voyage to Guinea: “There is no small number of Men in Europe who believe that the Gold Mines are in our Power; that we, like the Spaniards in the West Indies, have no more to do but to work them by our slaves. Though you perfectly know we have no manner of access to these Treasures, nor do I believe that any of our People have ever seen one of them: Which you will easily credit, when you are informed that the Negroes esteem them Sacred and consequently take all possible care to keep us from them” (80). William Snelgrave complained in his travel narrative that he “could never obtain a satisfactory account from the Natives of the Inland Parts” because of their “Jealousy,” determined, as they were, to keep their trade routes to themselves (Preface).

iv Jeremy Wear sees resonances with Defoe’s description of Africa’s material wealth in Captain Singleton and Singleton’s own desire to locate the Northwest Passage later in the text (573). Indeed, for a time, the notion of a river route through Africa was as compelling to geographers and navigators as the notion of a sea route through the Arctic.

v Incidentally, Moll provided maps for Robinson Crusoe.

vi Baker and Gary Scrimgeour note that Captain Singleton evokes the maps of Africa available at the time—particularly in how detailed coasts “fad[e] into gross inaccuracies about the hinterland and pure conjecture as to the nature of the interior” (Scrimgeour 22). In his biography, Max Novak observes the irony of the fact that “Defoe occasionally mocked map-makers who drew designs or monstrous figures where they had no information about the terrain, but in Captain Singleton he too had to create an imaginary Africa” (584). Novak does not comment on whether this incongruity might, in fact, be Defoe expounding on this mockery.

vii Defoe wrote propaganda for the RAC when they were struggling in the 1710s, including two tracts—An Essay Upon the Trade of Africa (1711) and A Brief Account of the Present State of the African Trade (1713)—and several updates on the parliamentary case over whether the company should be allowed to maintain its monopoly in The Review in 1709-13. See Kiern 244; Knox-Shaw 940-41. See also Scrimgeour 21-22; Wheeler 136; Novak 361. Though Defoe held “conflicting attitudes toward slavery” (Knox-Shaw 942), his enthusiasm about proto-colonial trade investments in Africa is legible in several of his works, including A History of Discoveries, The Advantages of the East-India Trade to England Considered (1720), and his contributions to the Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis (1728).

viii As Paula Backscheider observes about Defoe’s A History of Discoveries, “One of Defoe’s great strengths as a writer of history was his knowledge of geography” (114), and she suggests that “Much of the persuasive power of Defoe’s case for increased colonization comes from the range and details of his geographic descriptions” (114-15). Defoe wrote about the importance of geography to a good education in a short 1725 essay, “On Learning.” And although even contemporary critics sometimes accused him of being an “ignorant scribbler” where his own geographical representations were concerned (qtd. in Baker 263), “he certainly made use of the latest and best geographical material available” (Baker 263).

ix Several critics have read Captain Singleton with an eye toward this ambition. Wheeler argues that the fact that “The novel envisions an Africa emptied of commercial infrastructure, including trading and communication networks” (108) allows it to “rehers[e] certain cultural fantasies of expanding the empire through plundering Africa and describing a continent ripe for European commercial development” (109). Ian Newman suggests that these types of readings have been “the most productive accounts of Captain Singleton in recent years” for how they “interpret the novel as part of a discourse that seeks to define the human in a colonial context and considers the agency afforded to representations of the native communities that Singleton encounters as he journeys across Africa” (567). Wear refers to “Singleton’s walk across Africa” as “more an act of commercial reconnaissance than a nature hike,” and argues, “In Africa, Defoe implicitly suggests, infinite exploitation is the key to the accumulation of wealth” (588). Indeed, Captain Singleton stages many of Defoe’s ideations about African conquest; however, I suggest these ideations are also in tension with, and sometimes modulated by, Defoe’s occupation with geographical accuracy.

x Defoe invokes this indeterminate space between somewhere and nowhere in other works to denote a place that has material reality but is outside human comprehension. In An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727), he describes the dwelling place of spirits who are not “embodied and cased up in flesh, . . .who inhabit the unknown Mazes of the invisible World, those Coasts which our Geography cannot describe; who between Some-where and no-where dwell, none of us know where, and yet we are sure must have Locality” (4; emphasis original). In his poem A Hymn to Peace (1706), Defoe similarly describes a “Dark abode” that “No geography” can “describe” (11), one “Where weak Aspiring Nature soars too high;/ Which Handmaid Sense, bewilders and Confounds,/ With Reasons ill adapted Tools:/ Attepts to squareth’ Extent of Souls,/ As Men mark Lands, by Butts and Bounds” (10).

xi Jeremy Wear refers to this as the novel “give[ing] scientific discovery the taint of self-interest, which suggests a continuum of piratical acts” (574). For more on how pirates, buccaneers, and privateers navigated the line in their writings between criminal adventurers and scientific observers, see Frohock.

xii Neil Rennie calls Defoe’s narrative technique “a plain and simple style designed as a medium to convey strange and distant ‘facts’ to a skeptical and civilized reader, half a world away” (81).

xiii As Manushag Powell and Frederick Burwick argue, “performance is continually, regardless of medium, the key to a pirate’s successful mobility” (11).

xiv Wheeler also points out that Defoe “significantly alters the conditions of contact characteristic of contemporary eyewitness accounts” (107-08) by homogenizing the people and landscapes of what was often thought of in the eighteenth century as a diverse part of the world. George Boulukos goes so far as to propose that Defoe’s Africa in Captain Singleton is “precisely the opposite of commercial travelers’ accounts,” and that his “totally barren Africa…represents the most uncommon vision” of the continent in the eighteenth century (53). These are important distinctions to make since they reinforce the fact that, regardless of how commercially appealing Defoe’s treasure trove version of Africa might be, it was likely taken with a grain of salt by most eighteenth-century readers. However, the distance between the representational strategies broadcast in both Defoe’s fiction and eyewitness accounts appears not so wide as either Wheeler or Boulukos suggest if the text is critiquing rather than espousing the way many geographical representations flattened out specific details in favor of broad, homogenous depictions.

xv This proverb, often translated as “Every year Africa is bringing forth some new monster,” appears in almost every travel narrative about Africa published throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For more on the history of the proverb, see Feinberg and Sodolow.

xvi John Ray was the first person to define species by whether they could breed across type in his 1686 History of Plants.

xvii It is, in fact, Singleton’s enslaved guide from Mozambique, the Black Prince, who enables him to both fend off these wild beasts and who gets Singleton and the crew through the interior of the continent alive. I examine the implications of this and what it suggests about the African underpinnings of Enlightenment geographical knowledge in a book-length project in progress.

Aravamudan, Srinivas. Tropicopolitans: Colonialism and Agency, 1688-1804. Duke UP, 1999.

Backscheider, Paula. Daniel Defoe: His Life. Johns Hopkins UP, 1989.

Baker, J. N. “The Geography of Daniel Defoe.” The Scottish Geographical Magazine 47.5, 1931, pp. 257-69.

Bosman, Willem. A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea. London, 1705.

Boulukos, George. The Grateful Slave: The Emergence of Race in Eighteenth-century British and American Culture. Cambridge UP, 2008.

Burwick, Fredrick and Manushag Powell. British Pirates in Print and Performance. Palgrave, 2015.

Caillois, Roger. “Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia.” The Edge of Surrealism: A Roger Caillois Reader. Ed. Claudine Frank. Trans. Claudine Frank and Camille Naish. Duke UP, 2003, pp. 89-105.

Defoe, Daniel. “An Account of the Commerce of the Several Countries on the Sea-Coast of Africa.” Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis. London, 1728, pp. 263-276.

—. The Behavior of Servants in England Inquired Into. London, 1726.

—. Captain Singleton. London, 1720.

—. An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions. London, 1727.

—. A History and Principal Discoveries and Improvements. London, 1726.

—. A Hymn to Peace. London, 1706.

—. “On Learning.” Daniel Defoe: The Second Volume of his Writings. Ed. William Lee. London: 1862, pp. 435-439.

—. A New Family Instructor. London, 1732.

—. Robinson Crusoe. Ed. John Richetti. Penguin, 2003.

Feinberg, Harvey M. and Joseph B. Sodolow. “Out of Africa.” Journal of African History 43, 2002, pp. 255-61.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of Human Sciences. Vintage, 1970.

Frohock, Richard. Buccaneers and Privateers: The Story of the English Sea Rover, 1675-1725. Delaware UP, 2012.

Jobson, Richard. The Golden Trade: Or, A Discovery of the River Gambra, and the Golden Trade of the Aethiopians. London, 1623.

Johnson, Samuel. “Introduction.” The World Displayed. Vol. 1. London, 1759, pp. iii-xxxi.

Kiern, Tim. “Daniel Defoe and the Royal African Company.” Historical Research 61, 1988, pp. 243-47.

Knox-Shaw, Peter. “Defoe and the Politics of Representing the African Interior.” Modern Language Review 96.4, 2001, 938.

Livingstone, David. Putting Science in its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge. Chicago UP, 2003.

Loar, Christopher. Political Magic: British Fictions of Savagery and Sovereignty, 1650-1750. Fordham UP, 2014.

Moore, Francis. Travels into the Inland Parts of Africa. London, 1738.

Newman, Ian. “Property, History, and Identity in Defoe’s Captain Singleton.” SEL 51.3, 2011, pp. 565-83.

Novak, Maximillian. Daniel Defoe: Master of Fictions. Oxford UP, 2001.

Pearl, Jason. Utopian Geographies and the Early English Novel. Charlottesville: Virginia UP, 2014.

Pliny the Elder. The Historie of the World: Commonly Called, the Natural Historie. Trans. Philemon Holland. London, 1634.

Rennie, Neil. Far-Fetched Facts: The Literature of Travel and the Idea of the South Seas. Clarendon, 1995.

Rogers, Pat. “Speaking Within Compass: The Ground Covered in Two Works by Defoe.” Studies in the Literary Imagination 15.2, 1982, pp. 103-13.

Scrimgeour, Gary. “The Problem of Realism in Defoe’s Captain Singleton.” Huntington Library Quarterly 27.1, 1963, pp. 21-37.

Snelgrave, William. A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave-Trade. London, 1734.

Swift, Jonathan. “On Poetry: A Rapsody.” Miscellanies, in Prose and Verse. Vol. 5. London, 1735, pp. 160-178.

Turley, Hans. “Piracy, Identity, and Desire in Captain Singleton.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 31.2, 1997, pp. 199-214.

Wear, Jeremy. “No Dishonour to be a Pirate: The Problem of Infinite Advantage in Defoe’s Captain Singleton.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 24.4, 2012, pp. 569-596.

Wheeler, Roxann. The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture. Pennsylvania UP, 2000.