“Lord! what a miserable creature am I?”

-Robinson Crusoe

CRUSOE WAS CERTAINLY no Linnaeus. The word creature appears some 114 times in Robinson Crusoe (1719), and while it is almost exclusively deployed to signify an animal that Crusoe cannot identify, it also snakes its way into the characterization of human others. The indistinguishable nature of creatures thwarts Crusoe, and the unsteady use of the word inhibits his ability to distinguish a creature, ostensibly defined by animality, from a human. The word first appears following the shipwreck that waylays Crusoe and Xury: “as soon as it was quite dark, we heard such dreadful Noises of the Barking, Roaring, and Howling of Wild Creatures, of we knew not what Kinds, that the poor Boy was ready to die with Fear, and beg’d of me not to go on shoar till Day” (22-3). Xury’s excessive creaturely zoophobia—so extreme that he might “die with Fear”—is meant to foster Crusoe’s indomitable masculinity, situating him as protector-extraordinaire, especially of young racialized boys. Xury is, of course, Friday in beta test form. Yet, as Crusoe’s journal turns to his final years on the island, there is a sudden semantic shift in the term creature. “I was now entred,” he narrates, “on the seven-and-twentieth Year of my Captivity in this Place; though the three last Years that I had this Creature with me ought rather to be left out of the Account, my Habitation being quite of another kind than in all the rest of the Time” (193, emphasis added). “This Creature” to whom Crusoe refers is none other than Friday.

This essay examines the recycling of the word creature throughout Robinson Crusoe to trace and thus apprehend its unsteady and opaque significations.i First used by the narrative to signify indeterminate animality, Crusoe’s pronouncement of Friday as also belonging to creaturedom bespeaks the slippage between the human and nonhuman. Such an opacity becomes even more muddied when, after leaving the Island of Despair, the word creature is bestowed on the bear—“a vast monstrous One it was, the biggest by far that ever I saw”—who Friday first antagonizes and then shoots in the head for putative entertainment (247). To visualize the precarity of animality, I trace how Crusoe registers nonhuman animals, Friday, and, in a lone moment, himself as creatures, in a trajectory that corresponds with what Laurie Shannon calls “zoography.” For Shannon, “early modern writing insists on animal reference and cross-species comparison, while at the same time it proceeds from a cosmological framework in which the sheer diversity of creaturely life is so finely articulated” (8). While the novel may reflect a diversity of creatureliness—that is, who or what might be considered a creature—the granular specificity of what constitutes a creature is deliberately nebulous and rarely consistent. Thinking alongside environmental literary criticism and postcoloniality, the bearbaiting scene helps us better comprehend how both the racialized human other—Friday—and the animal are paired as some form of comedic minstrel by way of Crusoe’s deployment of the term creature.ii I argue that Robinson Crusoe ultimately encodes an alchemical calculus wherein the designation of creature—in the moments I map here—confers an unstable hybridity wherein human and animal bodies mesh with profound yet troubling effects.iii My premise is not that the bear becomes human or that Friday becomes animalized; instead, I am interested in how Crusoe’s narrative repurposes the appellation creature to signal a radical otherness that incites violent engagement and results in the dispossession of stable identity categories: human, colonist, racialized companion. As the novel demonstrates, creatureliness, at its core, renders unsettling, befuddling, and titillating effects that blur boundaries and unmoor human supremacy.

The circulation of creatureliness, as scholars have demonstrated, is fundamental to apprehending Crusoe’s companion species while on the Island of Despair, and Defoe’s works more generally.iv Stephen H. Gregg has recently argued for the instability of human and animal categories in Defoe, though not in Robinson Crusoe, emphasizing how such a binary is obfuscated by issues of comportment (with regards horses) and cognition (with regards to swallows and hounds).v In Animals and Other People, Heather Keenleyside notes of Robinson Crusoe that “Creatureliness is a major thematic preoccupation of the novel, and the central telos of its plot” (64). Keenleyside is invested in Crusoe’s creaturely companions that make visceral the logics of speaking (to and with) and eating (or being eaten by). “Crusoe,” she writes, “senses the precariousness of his status in a creaturely world in which human sovereignty is neither possible nor justified—a world in which persons are personified creatures, and ‘some-body to speak to’ can also be something to eat” (90). The consuming, precarious creaturely world that Keenleyside highlights is an important springboard for this discussion, and also for considering the hierarchy that might (consistently) impose the human above the nonhuman. Diverging from Gregg’s and Keenleyside’s analyses, I consider a broader spectrum wherein creatureliness is not a particular affect or ability, but rather a subtle reminder of mutable, interchangeable, and constantly fungible human and nonhuman positions. Perhaps more macrocosmic in outlook, I am interested in the loose use of creature, which varies contextually to denote an otherness characterized by inferiority, animality, sickliness, and/or race. Variety is the hallmark of creatureliness, especially in the ways its invocation repositions and dispossesses.

In concert with Donna Haraway’s provocation that animals are not “surrogates for theory; they are not just here to think with,” I magnify the oft-forgotten moment between Crusoe, Friday, and the bear to underscore the instability of creaturely hybridity while also drawing attention to depictions of animal cruelty that masquerade in the novel as comedy (5). Though I have yet to locate materials that would demonstrate that Defoe witnessed, or advocated for or against, bearbaiting, Robinson Crusoe unmistakably stages an execution of the bear, which reframes depictions of injustice and tyranny as power abuses exercised only by human actors.vi Reading the ursine moments in the novel and in relation to Aesop’s Fables and graphic cultural histories of bearbaiting, I attend to the recurrence of the bear throughout the early eighteenth century as a figure that serves as a didactic foil to the human, both physiologically and morally. In both Aesop’s Fables and Robinson Crusoe, the potential yet never realized violence enacted by the bear defines, by contrast, the actual and perpetrated violence wielded by the human. Put another way, in both episodes neither bear enacts harm. Such (sole) anthropocentric violence intends to mark the human (male) figures as impenetrable and superior. Yet, the novel’s use of creature undermines such static conceptions of stalwart dominance. Though painted with humorous hues, the bearbaiting moment disguises a frightening realization: it emblematizes the slippery and elusory ways in which nonhuman animality and racialized otherness are positioned as competing entities for superiority. This battle royale is mediated by gross violence and death. In Perceiving Animals, Erica Fudge opens with bearbaiting to consider the blurring of the human-animal boundary that incites and reifies modalities of animal cruelty.vii “The violence,” she writes, “involved in taming wild nature—in expressing human superiority—destroys the difference between the species” (19). I see Robinson Crusoe’s articulation of creature and depiction of bearbaiting to similarly dissipate difference. The novel’s creaturely bent exemplifies the uneasy status of human supremacy and induces a taxonomic indeterminacy that violently exposes the fragility of the human/nonhuman divide.

Ursine Origins

Crusoe’s interaction with the bear is a short anecdote, one that is rarely anthologized or remembered. In this episode: Friday and Crusoe traversing the borders of France and Spain by way of the Pyrenees encounter a pack of wolves (more on this later) and, immediately after, a bear. Friday deliberately engages in bearbaiting in an effort to please his gleeful audience. Friday, Crusoe narrates, intends to “g[i]ve us all (though we were surpriz’d and afraid for him) the greatest Diversion imaginable” (246). Crusoe notes that despite the shock of finding a bear, it “offer’d to meddle with no Body” (247). Friday antagonizes the bear by pelting it with stones. The bear (with good reason) turns against the group. Friday scales a tree; the bear follows. Friday climbs down from the tree; the bear follows. And on the bear’s slower descent, Friday “clapt the Muzzle of his Piece into his Ear, and shot him dead as a Stone” (249).

Generally considered a “sport,” animal-baiting—including but not limited to bearbaiting, bullbaiting, horsebaiting, monkeybaiting, and lionbaiting—has a deep early modern history, which resurfaces in this anecdote.viii Rampant from at least the twelfth century until the nineteenth, bearbaiting was the practice of capturing bears—exclusively from the continent because bears are not native to England—chaining them to posts and siccing dogs upon them in a fight to the death.ix For Rebecca Ann Bach, animal baiting, especially bear and bullbaiting, is centrally about dominion and its reinscription of the anthropocentric and colonialist prepotence found in Genesis (22-3). Fudge agrees that baiting exemplifies iniquitous power distortions, suggesting that it “reveals the truth about humans,” namely that “to watch a baiting, to enact anthropocentrism, is to reveal, not the stability of species status, but the animal that lurks beneath the surface […] The Bear Garden makes humans into animals” (15). As Jason Scott-Warren explains, bear-gardens (the socially-condoned site of these fights) were figuratively “a place of strife and tumult,” and literally, a proto-zoo where bears were chained and confined for the deliberate purpose of canine and human antagonism (63). In line with this antagonism, throughout the seventeenth century, the bear gardens that abutted the Southbank of the Thames were sites of enduring debauchery and were so popular that, “the large and often dangerous crowds which assembled on the Bankside caused the authorities much uneasiness” (Hotson 278). Bearbaiting was officially outlawed in 1835 but declined, in A.S. Hargreaves’s words, “only slowly” (n.p.). Crusoe’s framing of the bear vignette recapitulates bearbaiting as an entertainment commodity, but forgoes the usual artificial setting and locates the sideshow in the bear’s native place.

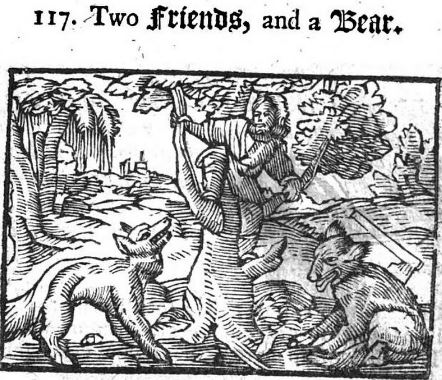

Defoe’s bear episode would not have been, for eighteenth-century audiences, a non sequitur. Thomas Keymer pinpoints Defoe’s potential source for the vignette: a January 1718 article in Mist’s Weekly Journal (a publication to which Defoe contributed) records villagers near Languedoc attacked by “a troop of wolves and six bears” (306).x In addition to this source, at least one of its cultural antecedents lies in Aesop. Aesop’s Fables resonated widely with the long eighteenth-century reading public, as is evidenced by the countless editions, revisions, and republications of the morally-didactic narratives meant for even the “Meanest Capacities.” Published just a decade before Robinson Crusoe, A New Translation of Aesop’s Fables, with cutts (1708) features three anecdotes that showcase a bear.xi The second of the three, “Two Friends, and a Bear,” details two companions wandering the forest when they stumble upon a bear. The first friend, steeped in adrenaline and fearful for his safety, ascends a nearby tree. The second friend, also fearful for his safety but a less gifted tree climber, flops on the ground and plays opossum. The bear, excited by the commotion but too lazy to scale the tree, paws at the second friend, but he [the bear] “found no Breath nor any Appearance of Life, disdain’d the Carkass, and Walks off and leaves him” (Aesop 157). The bear having left the two, the first friend descends from his arboreal sanctuary, and pointedly asks the second “what the Bear whisper’d in’s Ear” (Aesop 157). The second friend reveals the bear’s infinite erudition: keep better company. A moral about friendship immediately follows:

Chuse not an empty Talker for a Friend:

Fair Complements, but weakly recommend.

True Friendship most substantial Weight must bear.

Professions, without Service, are but Air. (Aesop 158)

“Two Friends, and a Bear” clearly makes a proxy of the bear—the pun on “must bear” illustrates this—by which valuable human friendships are put to the test. Aesop’s bear then operates as an animal sage disseminating fortune-cookie-like platitudes, but, as with Crusoe’s bear, the ursine inclusion invites readers to see beyond mere symbolism.

I invoke “Two Friends, and a Bear” in correspondence with the ursine interaction in Robinson Crusoe for several reasons, least of all being that bears surface in both. Not only do the episodes extend a cultural fascination with the bear in its native place (and thus a growing awareness of animal natural history and an emerging ethological science), but paired together, these two excerpts draw the reader’s attention to bear faces: the secrets bears whisper in confidence in the fable and Friday’s ursine assassination. Both demonstrate an important proximity of bear and human faces, especially as this facial intimacy may pertain to aurality.xii Both Defoe’s and Aesop’s illustrations access and recapitulate a mythos about the bear that would have been debunked but available to an early modern audience. As Catherine Loomis and Sid Ray suggest, “bear whelps were thought to be born as lumps of matter—sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything—that the mother bear then licked into shape” (xvi). The potential for bear mouths, especially maternal bear mouths, to effect into being is fundamentally a gesture of worldbuilding.xiii There is then something about the bear mouth that enacts a genesis by way of the tongue. In Aesop, it is the bear who places its muzzle to the human’s ear: the bear is the arbiter of moral advice who pushes the second friend to an epiphany on friendship. The bear’s words “lick into shape” the moral reckoning. Defoe—writing after and during Aesop’s popularity in English print culture—implicitly or explicitly recycles this narrative through inversion. The bear in Defoe is mute and instead the ursine voice is transmuted through a pun on “muzzle.” When Friday “clapt the Muzzle of his Piece into his Ear,” the result is a punny elision of animal and object. The double meaning of “muzzle” positions it both as an extension of the gun, and thus the means of facilitating violence, and also a reframing of an animal’s muzzle or snout. The gun/animal elision suggests a particular ferocity and capability of violence, both of which can be harnessed for and by humans.xiv At the same time, Friday’s placement of the “muzzle” to the bear’s ear also instills a particular physical closeness, which is, of course, undergirded by violence.

Whereas Aesop’s bear may be merely instrument to the fable’s moral, the bear in Robinson Crusoe is not, and there is no moral to be learned from the episode. Even more, it is in this moment that Crusoe’s narrative confuses and repurposes the use of creature. Following the insistence that Friday’s bearbaiting is “the greatest Diversion imaginable,” Crusoe details a curious ethological history of the bear:

[T]he Bear is a heavy, clumsey Creature, and does not gallop as the Wolf does […] so he has two particular qualities […] First, As to Men, who are not his proper Prey […] he does not usually attempt them, unless they first attack him: On the contrary, if you meet him in the Woods, if you don’t meddle with him, he won’t meddle with you; but then you must take Care to be very Civil to him, and give him the Road; for he is a very nice Gentleman. (246-7)

These details are included in a single paragraph, a paragraph that offers the bear as both a “clumsey Creature” and a “very nice Gentleman.” The gendering of the bear aside, Crusoe’s explication of observational (but completely fictionalized) ursine behavior doubles-down on the overlap wherein creatures can simultaneously be gentlemen. Whereas Crusoe’s emphasis on creature here pinpoints a particular physiology—the bear’s weight and clumsiness confer creatureliness—the disclosure of the bear as gentleman follows an understanding of the bear as mirroring civility, which is itself not a physical characteristic but rather a personality trait—the way one comports oneself.xv The hybridity that Crusoe describes here locates creatureliness within the parameters of the body and gentility within the confines of cognition, emotion, and sociality. But this civility quickly sours, as Crusoe explains, when the bear has been affronted.

[I]f you throw or toss any Thing at him, and it hits him, though it were but a bit of a Stick, as big as your Finger, he takes it for an Affront, and sets all his other Business aside to pursue his Revenge; for he will have Satisfaction in Point of Honour; that is his first Quality: The next is, That if he be once affronted, he will never leave you, Night or Day, till he has his Revenge, but follows at a good round rate, till he overtakes you. (247)

Crusoe’s haunting depiction of bears as vengeful demons hellbent on satisfaction is jarring. What is unclear is if this subsequent depiction of the bear is somehow indicative of the animal’s creaturely state—animals can be affronted and enact retribution—or his gentlemanly state, which might suggest that the capacity for revenge is reserved for humans alone, a topos that is well-situated throughout eighteenth-century fiction. Regardless of what Crusoe intends to suggest here, it is the implicit violence that might accompany the revenge—“he will never leave you till he has his Revenge”—that muddies certifying the bear as either creature or gentleman, and acknowledges a blending of human and nonhuman capacities for revenge. For Crusoe, the bear is clearly both, but whether this elevates animals by way of anthropocentrism or derogates humans to vicious beasts remains unclear.

Friday, My Pet

Crusoe may be the David Attenborough of the bear episode, narrating it with an entertained but aloof distance, but Friday is the participant who deliberately engages the bear for the viewing pleasure of Crusoe and the other expeditioners. “O! O! O! says Friday, three Times, pointing to him [the bear]; O Master! You give me te Leave! Me shakee te Hand with him: Me make you good laugh” (247). Friday repeats this line three times, which seems to follow the triplet “O!” that marks both his excitement and some form of onomatopoeic expression meant to visualize Friday’s mouth in action. Crusoe’s insistence that Friday repeats himself three times has additional import given that this is the moment that triangulates the human/animal hybridity among Crusoe, Friday, and the bear. Put another way, Crusoe reminds us of this triplet repetition as a formal indicator that draws our attention to this scene, and in so doing, highlights the blurring that transpires between colonizer, colonized-racialized companion, and creaturely-gentlemanly bear. The violence conducted under the auspices of entertainment makes fuzzy the categories of creatureliness and colonization. Crusoe maintains little control over the entire episode and instead is at the mercy of Friday’s secretive bearbaiting mission and the bear’s somewhat unpredictable actions. Friday’s position as both colonial understudy and creature (by Crusoe’s assessment, at least) obscures his ability to properly dispense with the bear: that is, to kill it outright, rather than to engage with it in a playful, didactic way.

Back on the Island of Despair, Crusoe enfolds Friday into his island life as a means of domesticating the creature—a gesture of petkeeping—and blurring the boundaries between humanness and creatureliness. Srinivas Aravamudan has similarly read Friday as Crusoe’s pet, which, in Aravamudan’s larger characterization of petkeeping in Tropicopolitans, becomes an identity that mediates racialized otherness, obeisance, and inferiority: “Friday is also Crusoe’s pet, approaching him on all fours, digging a hole in the sand with his bare hands, following him close at his heels, and even calling his own father, Friday Sr., ‘an Ugly Dog.’” (75).xvi The concept of creature similarly blends these categories. “It came now,” Crusoe narrates, “very warmly upon my Thoughts and indeed irresistibly, that now was my Time to get me a Servant, and perhaps a Companion, or Assistant; and that I was call’d plainly by Providence to save this poor Creature’s Life” (171). In what follows, and under the auspices of religion, Crusoe morphs Friday into his industrious servant and companion, though the narrative does not release Friday from the confines of creatureliness. Turning to the last year of his durance on the island—and having fully proselytized Friday at this point—Crusoe details:

I was now entred on the seven-and-twentieth Year of my Captivity in this Place; though the three last Years that I had this Creature with me ought rather to be left out of the Account, my Habitation being quite of another kind than in all the rest of the Time. (193)

In one reading, Crusoe’s use of “this creature” to refer to Friday is innocent; it is merely a pet name that establishes familiarity and endears one to the other. But I am less convinced that Crusoe’s dependency and engagement with Friday is indicative of any form of mutual beneficence, which would be akin to a facile presumption of colonialism as that which is equally beneficial to colonizers and colonized. Despite teaching Friday to speak English, practice Protestantism, and model deft marksmanship, Crusoe’s recurrent reference to Friday as creature noticeably differentiates the two—Friday will never be Crusoe’s equal—while emphasizing the types of “pet names” or taxonomic categories that hierarchize their differences.

As with Xury, the journalistic narrative is adamant in reflecting the queer contingency the racialized other places on Crusoe. I employ “queer” here in its multitudinous dimensions: to acknowledge non-heterosexual relationality, to pinpoint a distortion of normative kinship models, and also in its baser form to signify strange, uncanny, or odd. Like Xury who seeks patriarchal Crusoe for protection from unknown and feral animal threats, Friday replicates this puppy dog act, a suggestive turn of phrase I will return to momentarily. Plotting his escape back home, Crusoe narrates his plan to Friday, who is incensed that Crusoe might wholly abandon him:

Why you angry mad with Friday? what me done? I ask’d him what he meant; I told him I was not angry with him at all. No angry! No angry! says he, repeating the Words several times; Why send Friday home away to my nation? Why (says I) Friday, did not you say you wish’d you were there? Yes, yes, says he, wish we both there, no wish Friday there, no master there. In a word, he would not think of going there without me. (190)

Crusoe’s paternalism is immersive and inescapable, and thus Friday’s intention to always be with his “master”—the first word Crusoe teaches him—underscores Friday’s reliance on Crusoe and positions him as subordinated sidekick.

Crusoe’s petkeeping practice similarly absorbs Friday into the fold, especially as it pertains to this moment of bearbaiting, resonating with the early modern practice of pitting one’s prized dog against the bear. The likeness I trace here is not an animalizing projection; it is one that Crusoe emphasizes in calling Friday—albeit playfully—a dog. Though Crusoe’s trusty dog dies earlier in the novel, Crusoe’s relationship with Friday seems to recast that human-master/animal-servant relationship through a literal pet name. And Crusoe underscores this in his humorous tête-à-tête with Friday during the bearbaiting: “You Dog [Friday], said I, is this your making us laugh? Come away, and take your Horse, that we may shoot the Creature” (248, emphases added). As Oscar Brownstein suggests in his overview of early modern bearbaiting,

Bears had proven themselves capable of imitating men for centuries by performing as gymnasts, wrestlers, and dancers; the bear’s size, strength, and upright fighting stance made him an inevitable sparring parting for the man-fighting mastiff. Thus in the traditional bear-baitings the gentry would wager on their own dogs in competition with others to score hits on several bears. (243)xvii

Friday is by Crusoe’s own words transformed into a “dog” that is risibly sicced on the bear.xviii Aravamudan reads Friday in mode with the trope of the enslaved human pet—Oroonoko being the exemplar—wherein the racialized, subservient body becomes the recipient of bodily violence, which is played out with comedic tones. But here, Friday is not the recipient of violence; he is the arbiter. In this same breath, Crusoe differentiates the appellation “dog” from “creature,” which seems to hierarchize the animal-other based on their proximity to and intimacy with Crusoe. Friday need no longer be creature because he has both been transformed into a dog—at least in title—and because creatures, in this context, are prey and recipients of violence. Even more strangely, Brownstein notes that “the bears and apes [and dogs forced upon them], unlike the bulls, were given human names” (243). Crusoe’s refusal here to use Friday’s non-consensually given name—that is, Friday—and instead to replace it with “dog,” positions Friday and the bear closer to one another in that neither are bestowed proper human names, which would seem to cast their lots together. This is cemented by the following sentence in which Crusoe uses the creature moniker to immediately refer back to Friday:

And as the nimble Creature run two foot for the Beast’s one, he turn’d on a sudden, on one side of us, and seeing a great Oak-tree, fit for his Purpose, he beckon’d to us to follow, and doubling his pace, he gets nimbly up the Tree, laying his Gun down upon the Ground. (248)

Friday in his navigation of the forest space becomes the creature, and the bear becomes a beast, which underscores an understanding of creatureliness for Crusoe as contingent on spatial distance and difference from his own embodiment, habits, and mannerisms.

The metamorphosis wherein Friday becomes creaturely in this moment is similarly echoed in the illustration to Aesop’s “Two Friends, and a Bear,” which I above located as an ursine cultural accompaniment to Robinson Crusoe. The woodcut that accompanies “Two Friends, and a Bear” seems to amplify the disorientation of this fable given that there are neither two human friends nor a bear illustrated (Fig. 1). Instead, the woodcut features two wolves—another creature of infinite importance with which I conclude—who have cornered a man in the crook of a tree. Despite this printing mishap, or, at best, considerable artistic license, I want to read the dissociative nature of the fable and the woodcut as integral to understanding the elision between human and nonhuman animal, especially as it may pertain to understanding the bear.xix In the woodcut, the two friends are transformed into animals themselves: one stands aggressively on the left while the other seems to pant in pain, perhaps a reaction to the axe lodged in its back. The aggressive wolf on the left comes to the defense of the wolf on the right, having successfully scared the hunter—a hunter that bears a striking resemblance to the illustration of Crusoe from the novel’s first edition—up a tree. By numbers alone, the woodcut seems to transmogrify the two friends into two wolves and the bear into the man. In both woodcut and fable, the single entity (bear/man) is the aggressor who is capable of doing harm, and the aggrieved parties are those two whose numbers exceed that of the singleton. Such a reading of this woodcut further mires the fungible, porous nature of animal/human hybridity that is at the heart of both Aesop’s Fables and Robinson Crusoe. The woodcut offers a visual illustration of the interchangeability of human/animal hybrids. Inasmuch that the woodcut does not portray the “creature” described by the accompanying fable, it is the woodcut alongside the fable that enables a discursive episteme wherein creatureliness is a status of ambiguous being.

Figure 1. Illustration from Aesop’s “Two Friends, and a Bear” in A new translation of Æsop’s Fables (1708). Google Books.

Bear-y Funny

In staging bearbaiting, Defoe provides an opportunity to reconsider Aesop’s narrative and the publisher’s woodcut in their rendering of human-bear relations. Despite Crusoe’s warning to readers to heed an encountered bear, Friday does not abide the caution and instead takes great pleasure in antagonizing the animal. Having successfully bid the bear to follow him up a tree, Friday prepares the cruel act that is meant to garner laughter: “Ha, says he [Friday] to us, now you see me teachee the Bear dance” (248). Upon seeing the bough shake, “indeed we did laugh heartily” (248). Like Crusoe’s didacticism before him, Friday here intends to relay this model of education by “teachee” the bear to dance. Whereas Crusoe’s lessons are seen as serious and useful—religion, gunmanship, food customs—this lesson is one that serves no use, and it is the uselessness of dance that subtends the humorous appeal. In order for the bear to learn the dance, Friday must first model it: “Friday danc’d so much, and the Bear stood so ticklish, that we had laughing enough indeed” (249). Friday’s bearbaiting coincides with and is an extension of Crusoe’s colonizing mission, and yet perverts that mission by making a comedy show out of a creature who is about to be ruthlessly and senselessly murdered.

But the dancing is not the “funniest” part of the episode; the murder is. “No shoot, says Friday, no yet, me shoot now, me no kill; me stay, give you one more laugh” (249). With his audience awaiting the graphic punchline, Friday descends the tree, picks up his rifle, and awaits the bear’s pursuit.

[A]t this Juncture, and just before he [the bear] could set his hind Feet upon the Ground, Friday stept up close to him, clapt the Muzzle of his Piece into his Ear, and shot him dead as a Stone. Then the Rogue turn’d about, to see if we did not laugh, and when he saw were pleas’d by our looks, he falls a laughing himself very loud; so we kill Bear in my Country, says Friday; so you kill them, says I, Why you have no Guns; No, says he, no Gun but shoot, great much long Arrow. This was indeed a good Diversion to us. (249)

Though bears are found in a variety of locations across the globe, it is unlikely that Friday would have been familiar with any bear species given the approximate location of the Island of Despair. Alexander Selkirk, the sensational figure on whom Crusoe is based, was found on what is today the San Fernández Islands—one of which was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966—off the western coast of Chile. The only species of bear indigenous to South America is the Spectacled Bear, which is found exclusively in the Andes Mountains. As Keymer notes with regards to the wolf attack that precedes the bear incident: “wolves in America are to be found as far south as Mexico, though not in Friday’s homeland” (306). Given the unlikelihood that bears too would be autochthonous to “Friday’s homeland,” Defoe makes a racialized proxy of Friday, which serves a troubling purpose. This minor detail metonymizes Friday as a racialized catch-all that appears as universally indigenous given his alleged familiarity with all forms of flora and fauna. The rendered effect engenders something like hybridity wherein Friday must navigate (often unsuccessfully, according to the narrative) human/animal and colonizing/colonized positions. It is the familiarity with nature—especially his knowledge of bears and wolves—that positions Friday as lesser than Crusoe, closer to animality, and thus less civilized. Such an implicit (racist) elision has historically vilified indigeneity and deprivileged indigenous modes of being and knowledge. Friday’s supposed foreknowledge of bears furthers this colonizing divide, drawing Friday closer to the naturalness of the bear (and thus wild) and further from Crusoe’s hallmark of “civilized” masculinity.

The appellation creature, though, returns immediately following the bear’s death, and it is this moment that tips the scales of understanding a fundamental aspect of creatureliness within the novel: deathliness. “We should certainly have taken the Skin,” Crusoe writes, “of this monstrous Creature off, which was worth saving, but we had three Leagues to go, and our Guide hasten’d us, so we left him, and went forward on our Journey” (250). Not only does the bear episode convey the moment of bearbaiting as humorous entertainment, but it renders the “monstrous Creature” detritus. A sense of creatureliness is then imbued with both its capacity to die an unimportant death and also to be death itself: to rot in place, brain matter spewed outwards. It is in this way that the bear as creature epitomizes the liminality at stake in one of the many definitions of the word offered by the Oxford English Dictionary: “a living or inanimate being.” The short-lived bear episode demonstrates the short-livelihood of creaturely habitation within the novel, especially as it mediates the necropolitical possibility of becoming death: a death that is neither useful nor can be used.xx The waste of the bear’s body—it is not eaten, shorn, or kept—reflects the uselessness of not only the ursine body but also of the senseless violence that similarly serves no point. By the narrative’s standards, the bear’s single value is a comical death that perversely satiates the travelers’ expeditionary ennui.

The sense that creatureliness is a mediation of the peripheries of life and death, though, becomes an epistemology (perhaps even an ontology) that Crusoe weaves throughout his narrative. In the singular moment wherein Crusoe refers to himself as creature, this mediation becomes abundantly visible. As the epigraph to this article foreshadowed, when Crusoe catches a fever on the Island, he cries out in anguish, “Lord! what a miserable creature am I? If I should be sick, I shall certainly die for want of help; and what will become of me! Then the tears burst out of my eyes, and I could say no more for a good while” (78). As with the bear, Crusoe registers an identical reading of creatureliness that signals sickliness and thus proximity to death. This is not to suggest that Crusoe sees the bear’s creatureliness similar to his own. Friday’s creatureliness may be adjacent to the bear’s, but Crusoe works diligently to describe himself as both different than and superior to both. In his exasperated state, Crusoe self-identifies as a “miserable creature” to approximate his near-death state, and thus his distance from the livelihood that is indicative of non-creatureliness. Creatures then are those enacted against, often without mercy, who fence-sit on the borders of life and death, often succumbing to the latter, thus positioning their existence as ephemeral, and with the case of the bear, meaningless.

Creatures Fight Back

The last use of creature in the novel does not refer to Crusoe, Friday, or the bear. Instead, following the bear’s death, the expeditioners face an onslaught of “ravenous” and “hellish” creatures: wolves (252-3).

But here we had a most horrible Sight; for riding up to the Entrance where the Horse came out, we found the Carcass of another Horse and of two Men, devour’d by the ravenous Creatures; and one of the Men was no doubt the same who we heard fir’d the gun; for there lay a Gun just by him, fir’d off; but as to the Man, his Head and the upper Part of his Body was eaten up. This fill’d us with Horror, and we knew not what Course to take; but the Creatures resolv’d us soon, for they gather’d about us presently, in hopes of Prey; and I verily believe there were three hundred of them. (252)

The multitudinous creatures that populate the narrative return in full force here, outnumbering with bloodlust. From these final moments of the novel, it is impossible not to locate a reading of the creature with an ominous foretelling of death, an uncomfortable radical otherness that stuns the human. Whereas the bear is the recipient of gross and allegedly humorous violence, it is the wolves who are capable of offering a retributive justice.xxi If the wolf is enfolded into the pack of all other creatures throughout the novel, then it is this attack that centrally demonstrates how creatureliness can dethrone human supremacy by reciprocating the exercise of violence. It is as if, in the amassing of “three hundred of them,” the novel’s creatures return—some borne from their deaths—in full, frightening force. But the creaturely retributive justice is not entirely successful. After killing “three Score of them [wolves]” and surviving the incident with Friday, Crusoe reiterates the threat of the creature:

For my Part, I was never so sensible of Danger in my Life; for, seeing above three hundred Devils come roaring and open mouth’d to devour us, and having nothing to shelter us, or retreat to, I gave my self over for lost; and as it was, I believe, I shall never care to cross those Mountains again: I think I would much rather go a thousand Leagues by Sea, though I were sure to meet with a Storm once a Week. (254-5)xxii

For Crusoe, creatureliness is escapable, but only within the thin margin of his life, and there are casualties: both human and nonhuman. The creature comforts (and often discomforts) Crusoe experiences and narrates into being are not singular objects that are bereft of agency, feeling, or possibility. Creatures, by the novel’s wielding, violate and are violated, enact revenge, and serve as reminders of a lesser state of being that is proximate to death. Robinson Crusoe then demonstrates the potential for the subaltern creature to intervene by forcing the renegotiation of hierarchies of supremacy, and that is of great comfort to this reader.

University of California, Santa Barbara

NOTES

iBorrowed from the French creatur, which is itself acquired from the Latin creātor, the word originally denotes a creator, founder, or appointed official, often within religious contexts. The Oxford English Dictionary reports five different noun uses of “creature,” which make following Defoe’s use of the word a fascinating, yet difficult, feat for close readers. By 1300, creature signified “a product of creative action” or could be used to suggest “a human being, often conjured up with affective feeling.” By the end of the fourteenth century, a creature could have referred to “a living or inanimate being; an animal as distinct from a person.” But this is complicated by the fact that in the next century, the term is used to signify both “a reprehensible or despicable person,” as well as “a material comfort, something that promotes well-being.”

ii Such an undertaking is in dialogue with John Morillo’s recent endeavor to unfetter a particular genre of animal semiotics held captive by Cartesianism within early modernity. In The Rise of Animals and Descent of Man, Morillo claims that “posthumanism [the dislocation of anthropocentrism and the emphasized visibility of nonhuman animals in philosophy] appears on the intellectual horizon during the eighteenth century” (xxiv). While I refrain from wading into the philosophical morass of posthumanism, Morillo’s examination of feeling for the animal and how such affects reorganize human subject positions is apposite here.

iii For a separate discussion of cultural/racial hybridity in the novel (specifically that of the Spanish sailors), see Roxann Wheeler’s “Racial Multiplicity in Crusoe.” Christopher Loar’s “How to Say Things with Guns: Military Technology and the Politics of Robinson Crusoe” also offers a reading of Friday’s hybridity within a colonial/postcolonial dialectic.

iv Lucinda Cole’s Imperfect Creatures magnifies a definition of the creature to emphasize its association with early modern vermin or, “a category of creatures defined according to an often unstable nexus of traits: usually small, always vile, and in large numbers, noxious and even dangerous to agricultural and sociopolitical orders” (1).

v See “Defoe’s ‘horse-rhetorick’: Human Animals and Gender” and “Swallows and Hounds: Defoe’s Thinking Animals,” respectively.

vi Defoe makes explicit mention of the bear garden—demonstrating its survival—in 1708 when he complains that his reading public has forsaken him. He writes, “Had the scribbling World been pleas’d to leave me where they found me, I had left them and Newgate both together […]? ‘Tis really something hard, that after all the Mortifications that they have been put upon a poor abdicated Author, in their scurrilous Street Ribaldry, and Bear Garden Usage, some in Prose, and some in those terrible Lines they call Verse […] whatever I did in the Question, every thing they think an Author deserves to be abus’d for, must be mine.” Daniel Defoe, An Elegy on the Author of the True-born-English Man, (London: 1708), 2.

vii Fudge, as if by kismet, also opens her book with the bear garden: “There was a Bear Garden in early modern London. In it the spectators watched a pack of mastiffs attack an ape on horseback and assault bears whose teeth and claws had been removed” (1). Andreas Höefele’s Stage, Stake, and Scaffold similarly opens with the bear garden as a way of situating the discussion of Shakespearean theater and what Höefele sees as parallel histories: animal abuse and capital punishment.

viii James Stokes’s “Bull and Bear Baiting: The Gentles’ Sport” demonstrates the popularity of animal baiting in Somerset in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. His graphs and images, which reveal the overwhelming practice, are particularly striking.

ix The dogs used for bearbaiting were often English bulldogs or English mastiffs. In many ways the dogs stand in for a particular form of English nationalism by way of canine identification. In Brownstein’s words, “to a large extent the story of bear-baiting is the story of the English mastiff, a particularly large and potentially ferocious animal for which England was famous as early as Roman times” (243). On bears’ extinction in England, see Brownstein 244.

x Keymer wagers that Defoe may have, in fact, written this piece (306).

xi Though I was unable to find a 1719 version of Aesop’s Fables, because there are editions published both before and after 1719, I have every reason to believe that this particular anecdote was circulating among a literate public at the time of Robinson Crusoe’s writing and publication.

xii Tobias Menely’s The Animal Claim offers another discussion of animal voices within the eighteenth century, especially with regards to sensibility and the cultural zeitgeist of sympathy.

xiiiKeenleyside’s chapter on Defoe and creatureliness focuses also on the mouth especially that of Poll, Crusoe’s parrot.

xiv See Christopher Loar’s “Talking Guns and Savage Spaces: Daniel Defoe’s Civilizing Technologies” in Political Magic for a separate reading of the fraught relationship between technologies of violence and the racialized other.

xv This description of the gentlemanly bear is resonant with Margaret Cavendish’s depiction of the “Bear-men” in The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World (1666) who are characterized as showing “all civility and kindness imaginable” (157). See John Morillo’s The Rise of Animals and Descent of Man, 1660-1800 for a reading of Cavendish’s animal hybridity.

xvi For another discussion of eighteenth-century petkeeping, see Laura Brown’s Homeless Dogs and Melancholy Apes.

xvii For a separate literary iteration of a similar moment, see Heinrich von Kleist’s “On the Marionette Theater” (1810) wherein a bear is endowed with uncanny humanoid abilities: fencing. I am grateful to Amelia Greene for this recommendation, and her careful reading.

xviii Brownstein notes the gambling aspect of this sport, and the investment in dogs: “But the spectator’s interest was in the dogs, their willingness, pursuit, attack, and tenacity; it was the dogs which won the prizes which were offered and it was the dog’s owners, primarily, who made the wagers” (243-4).

xix For a history of woodcuts and their recycled nature, see Megan E. Palmer “Cutting through the Woodcut: Early Modern Time, Craft and Media” and Kristen McCants, “Making an Impression: Creating the Woodcut in Early Modern Broadside Ballads,” both in The Making of a Broadside Ballad.

xx As J.A. Mbembe articulates in “Necropolitics,” the apogee of the state’s sovereignty is realized in the “power and capacity to dictate who may live and who must die” (11).

xxi For a later eighteenth-century essay that depicts wolf cognition and rationalizes lupine animosity towards humans, see “On the Intelligence of Animals” (1792).

xxii For a separate reading of the storm and new materialist forms of violence in Robinson Crusoe, see my forthcoming essay “Taken by Storm.”

WORKS CITED

Aesop. A new translation of Æsop’s Fables, adorn’d with cutts; suited to the Fables copied from the Frankfort edition: by the Most Ingenious Artist Christopher van Sycham. The Whole being redered in a Plain, Easy, and Familiar Style, adapted to the Meanest Capacities. Nevertheless corrected and reform’d from the grossness of the language, and Poorness of the Verse us’d in the now vulgar translation: the morals also more accuratel improv’d; together with reflections on each fable, in verse. By Joseph Jackson, Med. London, 1708. Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

Aravamudan, Srinivas. Tropicopolitans: Colonialism and Agency, 1688-1804. Duke UP, 1999.

Bach, Rebecca Ann. “Bearbaiting, Dominion, and Colonialism.” Race, Ethnicity, and Power in the Renaissance. Edited by Joyce Green MacDonald. Farleigh Dickinson UP, 1997, pp. 19-35.

“bear-baiting.” A Dictionary of British History. Edited by John Cannon and Robert Crowcroft. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3rd edition, 2015. Oxford Reference.

Brown, Laura. Homeless Dogs and Melancholy Apes. Cornell UP, 2010.

Brownstein, Oscar. “The Popularity of Baiting in England before 1600: A Study in Social and Theatrical History.” Educational Theatre Journal 21.3, 1969, pp. 237-250.

Chow, Jeremy. “Taken by Storm: Robinson Crusoe and Aqueous Violence.” Robinson Crusoe After 300 Years. Edited by Andreas Mueller and Glynis Ridley, Bucknell UP, Forthcoming 2018.

Cole, Lucinda. Imperfect Creatures: Vermin, Literature, and the Sciences of Life, 1600-1740. U of Michigan Press, 2016.

“Creature.” Noun. Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2018. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/44082

Defoe, Daniel. An Elegy on the Author of the True-born-English Man. London, 1708.

—. Robinson Crusoe. Edited by Thomas Keymer, Oxford UP, 2007.

Fudge, Erica. Perceiving Animals: Humans and Beasts in Early Modern English Culture. U of Illinois Press, 2002.

Gregg, Stephen H. “Defoe’s ‘horse-rhetorick’: Human Animals and Gender.” Topographies of the Imagination: New Approaches to Daniel Defoe. Edited by Katherine Ellison, Kit Kincade, and Holly Faith Nelson, AMS Press, 2014, pp. 235-250.

—. “Swallows and Hounds: Defoe’s Thinking Animals.” Digital Defoe 5.1, 2013, pp. 20-33.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Hargreaves, A.S. “bear-baiting.” The Oxford Companion to British History. Edited by Robert Crowcroft and John Cannon, Oxford UP, 2nd ed., 2015. Oxford Reference.

Höfele, Andreas. Stage, Stake, and Scaffold: Humans and Animals in Shakespeare’s Theatre. Oxford UP, 2011.

Hotson, J. Leslie. “Bear Gardens and Bear-Baiting during the Commonwealth.” PMLA 40.2, 1925, pp. 276-288.

Keenleyside, Heather. Animals and Other People: Literary Forms and Living Beings in the Long Eighteenth Century. U of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Loar, Christopher. “How to Say Things with Guns: Military Technology and the Politics of Robinson Crusoe.” Eighteenth Century Fiction 19.1-2, 2006, pp. 1-20.

—. Political Magic: British Fictions of Savagery and Sovereignty, 1650-1750. New York: Fordham UP, 2014.

Loomis, Catherine and Sid Ray, editors. Shaping Shakespeare for Performance: The Bear Stage. Farleigh Dickinson UP, 2016.

Mbembe, J.A. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15.1 2003, pp. 11-40.

Menely, Tobias. The Animal Claim: Sensibility and the Creaturely Voice. U of Chicago Press, 2015.

McCants, Kristen. “Making an Impression: Creating the Woodcut in Early Modern Broadside Ballads.” The Making of a Broadside Ballad. Edited by Andrew Griffin, Patricia Fumerton, and Carl Stahmer. Santa Barbara: EMC Imprint, 2016. http://press.emcimprint.english.ucsb.edu/the-making-of-a-broadside-ballad/woodcutting

Morillo, John. The Rise of Animals and Descent of Man: Toward Posthumanism in British Literature between Descartes and Darwin. U of Delaware Press, 2018.

“On the Intelligence of Animals.” The Lady’s Magazine and Repository of Entertaining Knowledge 1, Nov. 1792, pp. 270-77. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online.

Palmer, Megan E. “Cutting through the Woodcut: Early Modern Time, Craft and Media.” The Making of a Broadside Ballad. Edited by Andrew Griffin, Patricia Fumerton, and Carl Stahmer. Santa Barbara: EMC Imprint, 2016. http://press.emcimprint.english.ucsb.edu/the-making-of-a-broadside-ballad/woodcutting

Schiebinger, Londa. Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science. Rutgers UP, 2nd ed., 2004.

Shannon, Laurie. The Accommodated Animal: Cosmopolity in Shakespearean Locales. U of Chicago Press, 2013.

Scott-Warren, Jason. “When Theaters Were Bear-Gardens; or, What’s at Stake in the Comedy of Humors.” Shakespeare Quarterly 54.1, 2003, pp. 63-82.

Stokes, James. “Bull and Bear Baiting in Somerset.” English Parish Drama. Edited by Alexandra F. Johnston and Wim Husken, Rodopi, 1996, pp. 65-80.

Wheeler, Roxann. “‘My Savage,’ ‘My Man’: Racial Multiplicity in Robinson Crusoe.” ELH 62.4, 1995, pp. 821-861.